by Chuck Bushey

Meriwether William “Bill” Gabbert II of Senatobia, Mississippi died peacefully on January 14, 2023 at age 75 from cancer.

Nobody that I know ever called him Meriwether. He shared that name with Meriwether Lewis, half of the renowned Lewis & Clark Expedition, and Meriwether is the name of the canyon mouth adjacent to Mann Gulch above the Gates of the Mountain Wilderness on Montana’s Missouri River.

Bill and his siblings grew up in the same small rural town south of Memphis where he was born in 1947. After high school he went on to Mississippi State University for Agriculture and Applied Science (commonly called Mississippi State University) in the central Mississippi community of Starkville. I can imagine that the change from Senatobia, population about 3200 persons, to the much larger community of Starkville (about 11,400 people at the time) and entering into studies at the university must have been a major eye-opening change for Bill.

After navigating university life, Bill graduated with his B.S. degree in Forestry. As we all do upon graduating, it was time for him to make decisions on which direction to head next with a budding career. Bill decided to join up with the U.S. Forest Service to further his forestry interests and education, so he headed West to California and soon added wildland fire to his forestry toolbox. In actuality he probably didn’t have much of a choice about entering into wildland fire; at that time during the 1970s all USFS employees were “firefighters” in some capacity. It was a requirement that everyone understood; this was an organization that had been born into fire. Bill obviously took quickly to the challenge, joining up with his first fire crew, the El Cariso Hotshots, in California. This crew was one of the very first hotshot crews, established just after World War II on the Trabuco District of the Cleveland National Forest.

Bill truly enjoyed his seasons with the hotshots and he frequently mentioned in later years his memories from these days. Those memories weren’t all fun – they included the fatalities the crew suffered during the 1959 Decker Fire and the 1966 Loop Fire – the latter was still a fresh and sore memory when Bill joined the crew.

Fire crews of all types are wonderful places to develop lifelong friendships as people move through the fire seasons. This was also a time during which Bill quickly learned the ins and outs of the structure and politics within the wildland fire community, knowledge that would serve him well later in life. He ended up with 20 years of service in the U.S. Forest Service, and then transferred to the National Park Service (NPS) for another 13 years. He eventually retired as the Fire Management Officer for the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota; he was responsible for fire management on seven National Parks in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Nebraska. But he wasn’t even close to being finished with his fire career — he was just changing direction.

It was while Bill was with the NPS that I first got to know him. Bill was the Planning Section Chief on Rick Gale’s Type 1 Team based out of West Yellowstone, Montana during the 1988 Yellowstone Campaign. Our paths crossed whenever I would visit the fire camp there where I had established a USFS Northern Region (R1) satellite “Fire Behavior Service Center.” Yellowstone for that fire season was part of the R1 fire suppression responsibilities – what we all thought would be a “once-in-a-career” fire season.

Bill was obviously a very detail-oriented individual, a necessary and valued trait in that key position.

He and I met up again when he joined the IAWF as a new Board Member in 2004. He remained in that position for a year before assuming responsibilities as the IAWF’s brand new Executive Director (ED). Bill was a firm believer in the mission of IAWF– to promote communication within the global wildland fire community. He was the ideal detail-focused person to take on the director role, quickly organizing all of the disparate directions the association was growing into. Bill made it clear from the beginning that the ED role was not going to be a long-term job for him, and after a year under my term as IAWF President in 2008 he submitted his resignation.

At this time social media and blogging for many of us were still relatively new internet experiences. Bill had the idea of using these newish technologies in communication to further his ideas (and ours) regarding wildland fire communications. He quickly had Wildfire Today up and running – an online news site of wildland fire – with news stories spanning the globe but definitely U.S.-centric. His news updates and features and images and opinion pieces spread, and in 2012 he spun off a companion website which he called Fire Aviation, because this was a topic in wildland fire news that was growing in breadth and importance.

From the beginning these sites were a labor of love for Bill Gabbert, and a few of his passions quickly came to the forefront in his journalism, including what he called “students of fire.” He also focused on smoke impacts on firefighter health, political considerations of the jobs in fire, and perhaps most important, firefighter safety. He developed a wide-ranging global audience relatively quickly, and now and then he’d add on other expert authors and editors to round out and support both sites. He befriended and kept up with fire photographers and writers and editors — and agency leaders — not only in our relatively close wildland fire community, but internationally. He also made many friends in the fire-interested peripheral “public” – the tens of thousands out there who are interested in and connected with fire, such as family members, media, researchers, international fire personnel, and the large group of people who are just curious about the topic and how it influences our lives.

Bill Gabbert wrote on these topics almost daily, in a style that was easily understandable for readers who commonly get lost in or don’t care to digest the typical U.S. bureaucratic fire news.

Bill knew where to go and who to talk with to find the details he wanted, the core of the issue no matter the issue – he understood what was being said and could interpret or translate (without pulling any punches) for his readers. He had no qualms about writing on controversial fire topics, such as when Donald Trump and other politicians wanted to launch 4th of July fireworks from the heads of the Presidential sculptures at Mount Rushmore. This was just one of the Parks that had been Bill’s responsibility, and it’s a location with loads of highly flammable vegetation, at risk for trash and debris from fireworks with a history of both.

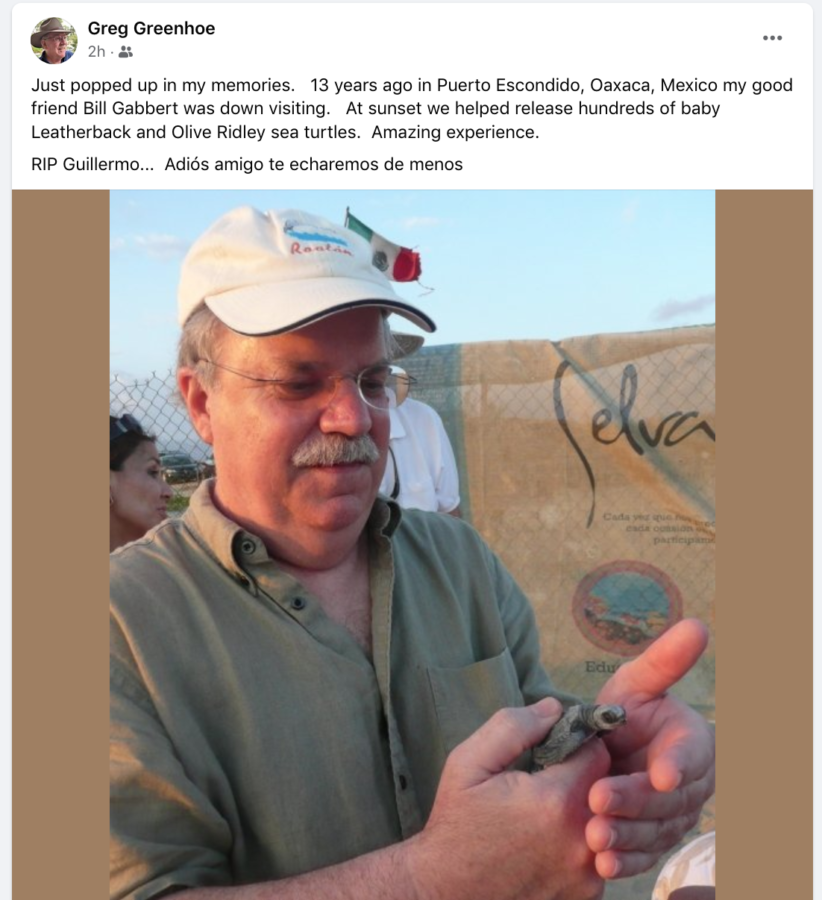

I wouldn’t call these efforts “work” for Bill. He loved doing it and being busy and involved “in the thick” of the wildland fire business, long after his official career retirement. These pursuits and activities of his also afforded him the opportunity to indulge in some of his other passions – including photography, motorcycle riding, and meeting up now and then with fire friends, which occasionally included a dark beer or two. His knowledge and networking skills also opened doors for him as a “retired” fire guy to occasionally work on short teams for hurricanes and other disaster response assignments, as well as traveling to international wildland fire events.

A few years after he had his sites up and running he and I had a discussion about the future of the successful work he had accomplished. It was a light conversation on succession, a topic that all organizations must have. I thought Wildfire Today would eventually be an excellent addition to the collection of communication organs that IAWF had developed. Bill had all sorts of new ideas he wanted to try out with the site, so he wasn’t at that point yet really interested, and truthfully IAWF wasn’t really ready yet either.

But the idea stuck in the back of our minds over the years. When Bill learned last year that he was terminally ill, he and IAWF began some talks about how a merger might be managed. I’m pleased to say Bill was happy that the IAWF Board agreed to take on the responsibility of moving Wildfire Today and Fire Aviation into the future — and it is an honor for IAWF to serve in this role. I’m sure he will be whispering in our ears as we advance the work he began and passionately served, as wildland fire news and communications become more vital around the world.

This collaboration has its roots back in 1998, when Mexico suffered through its worst fire season on record and was mounting a massive response to try to contain environmental damage and community threat. According to a

This collaboration has its roots back in 1998, when Mexico suffered through its worst fire season on record and was mounting a massive response to try to contain environmental damage and community threat. According to a