The map shows smoke created by the fires in Arizona today.

News and opinion about wildland fire

The video below attempts to answer the all-important question — “Can a “fitness model” (whatever that is) pass a New York Fire Department physical fitness test?” I won’t spoil the ending for you.

A question they DON’T answer: “Can a fitness model pass the Work Capacity Test?”, aka “Pack Test”? Do you think she could?

After I watched that video on YouTube, one of the “recommended” videos was titled TFFA Girls. It turns out that TFFA stands for Tucson Firefighters Association, and the video is a preview of the organization’s 2013 calendar, the female version. They also have a male calendar. I was unable to determine if the very fit women in the video, who occasionally wear turnout pants over bikinis, are actually Tucson firefighters.

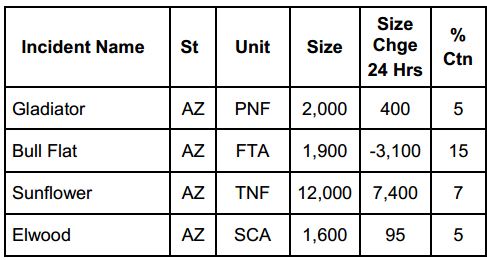

UPDATED 11:41 a.m. MDT, May 16, 2012

We will update the information and the maps of the fires in Arizona throughout the day on Wednesday. Check back for additional information, which is gathered from various sources, including the US Forest Service, Arizona state agencies, and the National Interagency Fire Center.

GLADIATOR FIRE

36 miles north of Phoenix, and 8 miles southwest of Mayer. It started as a structure fire in the community of Crown King.

Predicted drier weather and associated strong winds continue to complicate suppression efforts on the Gladiator Fire. Winds from the southeast and south are expected to push the fire north and northwest today.

Fire behavior is expected to be extreme. Firefighters continue working to suppress the fire and provide structure protection to homes. Firefighting resources will focus on perimeter control when they can do so safely. Crews are also working to protect structures and communication sites west of the fire. In areas where direct attack is not feasible, they will focus on protecting individual structures ahead of the fire.

An evacuation order remains in effect for the community of Crown King.

A Type 1 Incident Management Team (Incident Commander, Joe Reinarz) assumed command of the fire Monday afternoon.

(Additional information and maps about other fires in Arizona is below.)

Continue reading “Update: wildfires in Arizona – May 16, 2012”

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has released a report on the death of BLM Hotshot crewmember Caleb Hamm, who died from hyperthermia, a heat related illness. (The most severe form of hyperthermia is heat stroke.) Mr. Hamm was working on the CR 337 fire near Mineral Wells, Texas with the Bonneville Interagency Hotshot Crew when he collapsed and died July 7, 2011.

His parents, including his mother, Lynette Hamm, believe the official BLM report on the fatality has errors and suspects that the agency has not been completely forthcoming in an attempt to hide errors or mistakes in judgement. Ms. Hamm has said she wants all the facts to be disclosed so that other parents of firefighters will not have to bury their sons and daughters.

A television station in Utah, KSL, did a story on the incident.

Here is an excerpt from the article at KSL TV, which quotes Martin Buzbee, a city official from Mineral Wells, Texas who acts as the GIS mapping coordinator. :

…”I kept waiting and waiting for a medevac helicopter to be flown in and take care of the patient,” Buzbee said.

The medical helicopter and ambulance were parked just a few miles away. They were supposed to be called in according to the BLM’s own emergency plan, but the BLM was trying to use its own helicopter.

“They were reconfiguring a helicopter from the fire: from dropping water with a bucket, taking the bucket off and to try to medevac the patient in,” Buzbee described.

Eventually, the BLM did call in the civilian helicopter and ambulance. Official reports said the delay was 20 minutes; however, Buzbee believes it was more like 45 minutes.

Hamm was taken by ambulance from Drop Point Twenty and pronounced dead at the hospital. The incident was investigated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH concluded the 20 minute delay did not contribute to Hamm’s death. But Buzbee believes if the BLM had called the medical helicopter to the top of the hill immediately, it might have made all the difference.

Below is an excerpt from the NIOSH report which was released May 14, 2012.

==========================================================

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On June 23, 2011, a 23-year-old male seasonal wildland fire fighter (FF) on an interagency hot shot crew (IHC) deployed from his duty station in Utah to fight wildland fires in Georgia and Texas. After fighting fires in Georgia for 4 days, the crew was dispatched to Texas. After travelling for 3 days, then staging for 3 days, the crew began fire fighting on July 4, 2011.

On the morning of July 7, 2011, the FF was assigned swamper duties (clearing limbs after tree-cutting) to construct a fireline followed by cold trail operations (a component of mop-up) with a hand tool. After lunch, the FF refilled his water supply and continued securing the fireline and mopping up for about 1.5 hours. After being left alone for a short period of time, the FF was found unconscious at approximately 1550 hours. The weather was sunny and hot: a temperature of 105 degrees Fahrenheit (°F), relative humidity of 24% with minimal wind (1 to 3 miles per hour).

Initial assessment by the crew’s emergency medical technician (EMT) suggested the FF suffered from heat-related illness (HRI). Air Attack was notified as the crew EMTs provided basic HRI care at this remote location (the FF’s pack and shirt were removed, he was doused with water, and a tarp was held up for shade). Local emergency medical service (EMS) units (ambulance and Air Evacuation helicopter) were not notified of the incident for about 20 minutes due to uncertain drop point coordinates. This delay, however, did not delay advanced life support (ALS) treatment because it took 45 minutes to extract the FF to the drop point where the local EMS units were waiting.

Approximately 30 minutes after his collapse, the FF’s condition deteriorated; respiratory arrest was followed by cardiac arrest, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was begun.

Approximately 15 minutes after his cardiac arrest the FF arrived at the drop point and the local, ambulance and Air Evacuation units initiated advanced life support (ALS) but their treatment protocols for exertional heatstroke did not include cold/ice water immersion therapy. When the FF arrived at the hospital ED a core temperature of 108° F was documented and ALS continued for an additional 5 minutes. At 1703 hours the attending physician pronounced the FF dead and resuscitation efforts were stopped.

The autopsy report listed the cause of death as “hyperthermia.” NIOSH investigators agree with the Medical Examiner’s assessment. NIOSH investigators conclude that the FF’s hyperthermia was precipitated by moderate to heavy physical exertion in severe weather conditions. These factors led to exertional heatstroke.

All of the IHC members were exposed to heat stress (hot environmental conditions). Most IHC members interviewed by NIOSH reported symptoms consistent with HRI (feeling hot, feeling tired/fatigued/exhausted, weakness, headache, or nausea). Although indicators of heat strain were not measured (core body temperature, heart rates), on the basis of the environmental conditions and the reported symptoms, NIOSH investigators concluded that many of the IHC crewmembers had mild to moderate HRI.

Fatal exertional heatstroke is extremely rare among wildland fire fighters; this was the first reported case in the Agency’s 65-year history and only the second reported federal wildland fire fighter to die from heatstroke according to wildland fire service records. Agency records, however, show that less severe cases of HRIs and dehydration are more common; 255 cases occurred over the past 12 years. NIOSH considers cases of HRI to be “sentinel health events” [NIOSH 1986]. Sentinel health events are preventable diseases, disabilities, or deaths whose occurrence serves as a warning signal that preventive or therapeutic care may be inadequate [Rutstein et al. 1983].

To prevent HRI and heatstroke, a number of organizations have developed guidelines for determining when environmental conditions are too hot to continue training, sporting, or work activities. The environmental conditions during this incident exceeded these guidelines. NIOSH investigators offer the following safety and health recommendations to reduce heat stress, heat strain, and prevent future cases of HRI and exertional heatstroke among wildland fire fighters. Implementing these recommendations will demonstrate a continuing commitment to improve the safety culture of the wildland fire service.

====================================================

It is interesting that one of the NIOSH recommendations was to use a Wet Bulb Globe Thermometer (WBGT). In 1972 when I was on the El Cariso Hot Shots, a research organization paid the salary of one of the crewmembers that year, Tom Sadowski, to monitor three people on every fire, recording their pulse at regular intervals while they worked, what they ate, weather conditions, and other criteria. Tom also carried a WBGT, which was a thermometer with a three-inch black sphere on the end which had to be wet when readings were taken. The concept was that as the water evaporated the WBGT took into account the ambient temperature, the effect of wind on the evaporation, cooling from evaporation, and radiant heat from the fire or the sun. I don’t know what became of the research and the huge amount of data that Tom collected. Maybe there is a paper floating around out there somewhere.

UPDATE: Ken, in a comment, found the report from the study. The paper was first published in 1974 and a summary appears in a 1975 edition of Fire Management on page 16.

The recommendations the researchers made still seem applicable today. Interestingly, they suggest using a wet globe thermometer in order to “recognize heat stress situations”, which is similar to one of the recommendations made in the recent NIOSH report. This recommendation has been on the books for about 38 years. Maybe it’s time the agencies involved in wildfire suppression took action on it.

Perhaps every safety officer on a fire should have one when heat stress is a possibility. It might save a life.

Google Search found WBGTs listed for sale at $150 to $230.

====================

UPDATE May 16, 2012:

The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center and the International Association of Wildland Fire are hosting a webinar titled Wildland Firefighter Heat Illness Awareness and Prevention on May 17 at 1:00 p.m. PDT. More info HERE.

=====================

On August 21, 1937 in Wyoming, a cold front caused a 90-degree wind shift that changed the direction of spread of the Blackwater fire, which surprised and trapped a large number of firefighters, killing 15 of them.

The Billings Gazette has an interesting article about the fire, featuring an interview with Dave Sisk, a former smokejumper and incident commander of one of the Rocky Mountain Region’s Type 2 Incident Management Teams. Dave elaborates on some of the issues faced by the firefighters in 1937, contrasting them with the capabilities of today’s firefighters. For example, communication on the fire consisted of handwritten notes carried by runners. In the article, Dave is quoted as saying:

These guys in 1937 knew how to fight fire. What they didn’t know was that a cold front was off to the west heading in this direction.

There is a memorial honoring the firefighters along Highway 14/16/20 east of Yellowstone National Park. The photo below was taken during the ceremony dedicating the new memorial.

In July of 2005 I stopped at the memorial and there happened to be a small fire burning nearby at the time.

More information about the fire.

Thanks go out to Dick and Chris.