A Facilitated Learning Analysis has been released for the burnover that occurred July 16, 2021 on the Harris Fire near Joliet, Montana 25 miles northeast of Red Lodge. Dan Steffensen of Red Lodge Fire Rescue who had six years of experience with wildland fire was on a two-person engine crew when very strong winds suddenly shifted. He attempted to reach safety, but was overrun by the fast moving fire and was injured. Due to the severity of his burns, 2nd and 3rd degree on 45 percent of his body, Mr. Steffensen was flown to the University of Utah Burn Center in Salt Lake City where he was treated for nine weeks.

Mr. Steffensen was operating a nozzle while he and another firefighter who was driving the engine were making a mobile attack on a grass fire. It was burning in pastureland that had not been burned, grazed, or hayed in six years, consisting primarily of dense grass and some sage approximately two feet in height.

In accordance with department common practice, Mr. Steffensen was not wearing his line pack and fire shelter, as neither he nor the driver would ever get past the end of the hardline hose. In that first section, Mr. Steffensen was always in the driver’s direct line of sight, and the three-to four-foot flames “took down easy” and quickly.

The firefighters did not know that minutes before the burnover the National Weather Service had issued a Significant Weather Advisory for thunderstorms moving in their direction. “Wind gusts of 50 to 60 mph are possible with these storms,” it said. “A gust to 63 mph was reported in Big Timber with this activity.”

When the wind gusts arrived at the fire, increasing from 10 mph to about 55 mph, a helicopter pilot who had been dropping water was forced to jettison the water from his bucket.

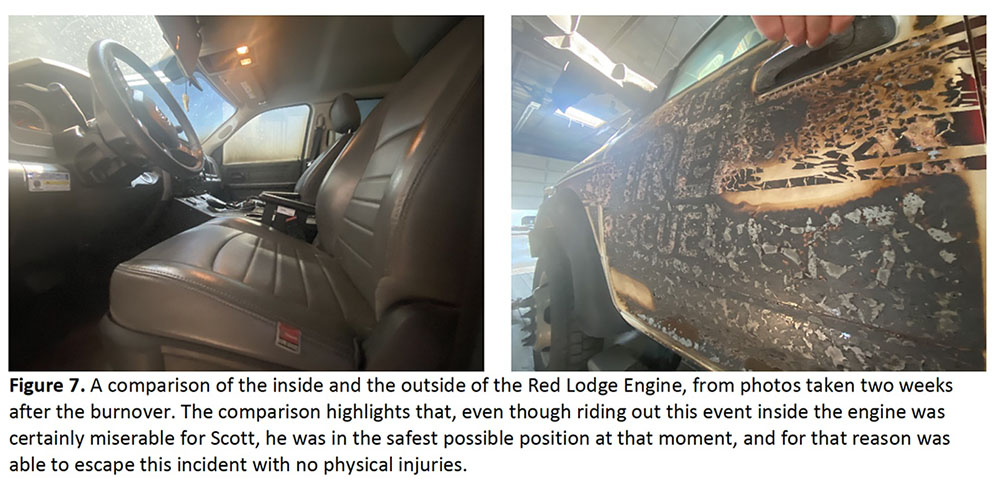

As the wind speed suddenly increased and the direction shifted, Mr. Steffensen and the engine were entrapped by flames. The firefighter driving the engine had no visibility and knowing there was a cliff nearby, stayed in place and let it burn over the engine. He later described it as being “hotter than hell in the cab” for the 20-30 seconds of the burnover. He was not injured.

From the report:

For Dan, those few seconds between when he recognized that they had a problem and when the flame front hit were not enough for him to return to the engine or reach the black. He later said “I’ve been on many fires, [and] I’ve never seen one come out of nowhere so fast. All it took was the wind switch.” Although he was only 15 or so feet from the burned portion of the field that he and Scott had just left, the fire was traveling too fast for him to get there. With no line gear on him, and no time to deploy a shelter even if he had carried it, he was left with just his PPE to protect him from the 20-foot high, fast-moving flame front, which hit him after slamming into the driver’s side of the engine and eddying under to the passenger side.

Below are the Key Takeaways from the report:

Almost every single experienced wildland firefighter reading this analysis will find the series of events recounted here familiar: an initial attack in light, flashy fuels with rapidly changing conditions. It can, therefore, be tempting to write this off as an unavoidable situation in an inherently risky profession. While the FLA team agrees that accepting some level of risk while fighting fire is inevitable, we do believe there are some key lessons for the reader to consider, should they ever find themselves in a similar situation.

1) Remember the importance of PPE and wearing it correctly. Dan’s injuries would have been much worse had he not been wearing his Nomex, a layered shirt, gloves, and a helmet in the appropriate manner.

2) Remaining in your vehicle during a burnover may be the best option in light, flashy fuels. Scott was able to walk away from the Harris Fire that day with no physical injuries. The comparison of the conditions inside and outside of E78 suggest that this was the safest place he could have been in that moment.

We also encourage you to reflect on the following questions, especially as they relate to fast-moving initial attack scenarios:

1) When planning your escape route, how much time do you really have to react? It was repeated throughout this analysis, both from individuals involved in the incident and those not involved, how common it is in our current firefighting environment to operate outside of the black. In this case, however, there were some slightly unusual circumstances, such as the high grassy fuel loads, that contributed to the unintended outcome. Take the time to consider such factors, as well as harder to predict factors such as unexpected wind shifts, when planning an escape route.

2) Is the higher level of risk that comes with missing elements of LCES acceptable to you? If yes, what values must be threatened for you to accept that higher level of risk? When asked, Scott shared that his major lesson learned from the day was, “what were we doing here?” With time to reflect, he regretted entering an unburned area with an inadequate escape route to save a few acres of grass, especially when an alternate suppression strategy may have been as effective at keeping the fire on the plateau.

3) What is the process in your organization for quickly communicating special weather statements and advisories about changing conditions? In this case, the special weather statement was issued only minutes before the thunderstorm impacted wind speed, direction, and fire activity at the scene, and no one on the fire received this information in time to react and reevaluate their tactics.

4) When the forecast restates the same thing every day, how do you ensure that you still account for the potential impacts of extreme weather during initial attack? Even if those on the hill had received the special weather statement in a timely manner, it had been hot and dry with a chance of thunderstorms in the area for weeks. Such repetition during fire season often results in the line of thinking that “nothing bad happened yesterday, so today we should be fine again.” Even for the most experienced firefighters, extreme fire weather should still be of note; in fact, these are often the firefighters that must battle most against complacency to objectively consider the potential risk posed by extreme fire weather.

5) Is your assessment of fuels valid? Just as in timber litter fuel types, there can be significant variations in grass fuels with regards to fuel loading and arrangement. In many areas of the west, grazing lands are enrolled in conservation programs that govern the frequency of grazing, haying, or burning, resulting in significantly higher amounts of fuel on the ground. How do you make sure that your assumptions about fire behavior and spread rates are still valid as you make decisions about tactics?