Originally published at 10:09 p.m. MDT, JUne 19, 2013

The photo above got my attention. It was posted on Twitter and Instagram by Chris Bronson, aka @cgb777.

My view from the plane of the Colorado wildfires. #colorado #wildfire http://t.co/yAHwRkZMP4

— Chris Bronson (@cgb777) June 20, 2013

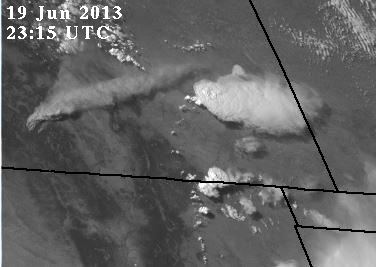

It’s a very impressive smoke plume. Since he said it was in Colorado I guessed that it was the West Fork Complex in south-central Colorado 14 miles north of Pagosa Springs, which was listed on InciWeb (when it was working – don’t get me started) at 8,000+ acres. So I fired up Google Earth and confirmed that the geography matched. Then I visited the NASA site for viewing GOES images and found the series of photos below that show primarily the southeast corner of Colorado, and also portions of NM, OK, TX, and KS.

After this last image at 0200 UTC (8 p.m. MDT) the later images are too dark to see anything.

Chuck Bushey sent me this link to an animated GOES 13 Rapid Scan Operations visible and 3.9 µm shortwave Infrared images for the same two fires and the same period of time. With the IR in the lower frame you can easily tell when the second, more southern, fire gets going.

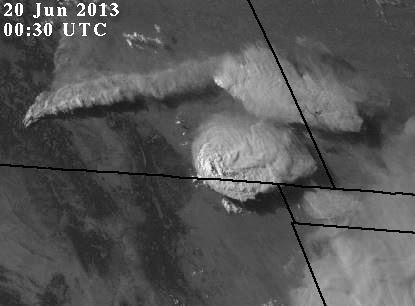

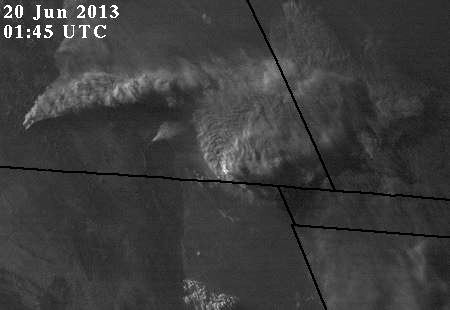

I thought it was interesting how the smoke plume in the four photographs above moved into space occupied by the large thunderstorm cell and appeared to force it to partially or mostly dissipate. Meteorologists out there can feel free to correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m thinking that there were at least two or three factors that caused it to happen.

- Warmer air in the plume lowered the relative humidity, reducing the condensation which formed the cloud; (I’m not too sure about this one; traveling over 200 miles, the plume probably cooled close to ambient temperature)

- The plume shaded the ground at the base of the thunderstorm cell, turning off its heat engine — less heated air rising = less condensation = less cloud;

- And this one I’m not too sure about either. Particulates in the plume served as condensation nuclei in the cloud. Moisture condensed on the particles, which then fell out as rain, dissipating the cloud.

- Or, heck, since the sun was setting, THAT turned off the heat engine, causing the thunderstorm cell to break up.

- Or all of the above?

It was also interesting how the scattered cumulus clouds on the Colorado/New Mexico state line in the span of 45 minutes formed into a large cumulonimbus cloud, which then seemed to merge or grow into the other one farther north near the smoke plume.

And then to make the photos even more interesting, a new smoke plume popped up in the last two photos between the West Fork Complex and the thunderstorms in the southeast corner of Colorado. As this is written at 10 p.m. Wednesday, this newer plume and fire does not show up on the Rocky Mountain Coordination Center map of current fires.

Hey, just came across this site. For anyone interested, here is the image at original resolution without the instagram effects. http://i.imgur.com/65ziv7Z.jpg

INCIWEB is useless at PL2….maybe IRWIN and FPA will fix it.

“InciWeb (when it was working – don’t get me started)”

I swear they are running that site on a old IBM 8088 …