On this day 109 years ago the fires of 1910 were burning across northern Idaho, Western Montana, and parts of Washington and Oregon. But on the following two days, August 20 and 21, winds fanned the flames into large conflagrations that raced across large expanses of the landscape, creating what became known as the Big Blowup.

During one of the fire fights U.S. Forest Service Ranger Edward C. “Ed” Pulaski told the 45 firefighters he was supervising to take refuge from an approaching wildfire in the 80-foot long Nicholson mine. When they began to panic in the smoky tunnel as the fire closed in, he drew his revolver, saying, “The next man who tries to leave the tunnel I will shoot”.

Ranger Pulaski’s name may have become lost in the dustbin of history, except for his penchant of tinkering with fire tools in his workshop. He became associated with what is now known as the pulaski tool that firefighters have used for over a century.

But perhaps he was given more credit than he deserved.

In 1986 the U.S. Forest Service publication Fire Management Notes published the article below about how the pulaski was actually developed.

The True Story of the Pulaski Fire Tool

James B. Davis

Research forester, USDA Forest Service, Forest Fire and Atmospheric Sciences Research, Washington, DC

The nickel-plated pulaski looks as good as new in its glass-fronted Collins Tool Company display case at the Smithsonian Museum of Arts and Industry in Washington, DC. Surrounded by equally shiny cutting tools of all description, the pulaski was first put on display at the Nation’s Centennial Exhibit in Philadelphia in 1876.

Conventional wisdom holds that the pulaski fire tool was invented by Edward C. “Big Ed” Pulaski in the second decade of the 20th century. Ed Pulaski, a descendant of American Revolution hero Casimir Pulaski, was a hero of the Great Idaho Fire of 1910, leading his crew to safety when they became imperiled. He was also one of a group of ranger tinkerers who struggled to solve the equipment problems of the budding forestry profession. However, the pulaski tool on display at the Smithsonian must have been made when Big Ed was no more than 6 years old!

In the early days of forestry in this country, fire tools were whatever happened to be available. The earliest methods of firefighting were confined mostly to “knocking down” or “beating out” the flames, and the tools used in the job were simple and primitive. The beating out, when such an approach was possible, was often accomplished with a coat, slicker, wet sack, or even a saddle blanket. A commonly used tool was a pine bough cut on arrival at the fire edge (4).

Soon farming and logging tools, available at general and hardware stores, came into use. These included the shovel, ax, hoe, and rake-all basic hand tools developed over centuries of manual labor. Even after firefighting became an important function of forestry agencies, these tools were accepted as they were, wherever they could be picked up, and little thought was given to size, weight, and balance. There appears to be no record of the use of the Collins Tool Company pulaski for fire control. Most likely, it was sold to farmers for land clearing and may have been forgotten by the late 1800’s (2).

With the advent of the USDA Forest Service and State forestry organizations, a generation of “ranger inventors” and tinkerers began to emerge. It became apparent that careful selection and modification was essential for efficient work and labor conservation. In the early days when almost everybody and everything had to travel by horseback transportation was a particular problem. For years foresters worked on the idea of combination tools. Most of the attempts were built in home workshops, and most “went with the wind.” Two important survivors, now in general use, are the Mcleod tool, a sturdy combination of rake and hoe, and the combination of ax and mattock. The McLeod was probably the first fire tool to be developed. It was designed in 1905 by Ranger Malcolm McLeod of the Sierra National Forest.

Who first invented the ax-hoe combination and used it for firefighting is a matter of minor dispute. Earle P. Dudly claims to have had a pulaski-like tool made by having a lightweight mining pick modified by a local blacksmith. He says he used the tool for firefighting in the USDA Forest Service’s Northern Rocky Mountain Region in 1907. Dudly was well acquainted with Ed Pulaski, and the two had discussed fire tools.

Another account of the origin of the pulaski is that William G. Weigle, supervisor of the Coeur d’ Alene National Forest, thought of the idea-but not for firefighting (5). Rangers Ed Pulaski and Joe Halm worked under him (all three became heroes of the Great Idaho Fire) at Wallace, then headquarters for the Coeur d’Alene National Forest. At that time, plans were being made for some experimental reforestation, including the planting, pine seedlings. As Supervisor Weigle planned the job, he decided a new tool was needed to help with the planting as well as other forestry work. He decided on a combination of ax, mattock, and shovel. One day in late 1910 or 1911, Weigle sent Rangers Joe Halm and Ed Holcomb to Pulaski’s home blacksmith shop to tum out a combination tool that might replace the mattock that was then in common use for tree planting. Halm, with Holcomb helping, cut one blade off a double-bitted ax, then welded a mattock hoe on at right angles to the former blade position. He then drilled a hole in an old shovel and attached it to the ax-mattock piece by means of a wing bolt, placing it so the user could sink the shovel into the earth by applying foot pressure to the mattock blade.

The rather awkward device was not a success as a planting tool. Probably the whole idea would have been abandoned had not Ranger Pulaski been fascinated with the possibilities of the tool. He kept using it, experimenting with it, and improving it. He soon discovered that the bolted-on shovel was awkward and unsatisfactory. He abandoned the shovel part and also lengthened and reshaped the ax and mattock blades. It is too bad Pulaski did not know about the Collins Tool pulaski — it would have saved him a lot of time. Nevertheless, by 1913 Pulaski had succeeded in making a well-balanced tool with a sharp ax on one side and a mattock or grubbing blade on the other.

Pulaski use now spread throughout the Rocky Mountain region. However, it was used not for tree planting but for fire control. By 1920 the demand was so great that a commercial tool company was asked to handle production.

Although the pulaski went into widespread use in the Rockies in the 1920’s, it saw little or no use in other areas. Prior to 1931 the USDA Forest Service had no good internal method for handling equipment development and promotion. Most new equipment ideas were introduced and discussed at the regular Western Forestry and Conservation Association meetings (3, 7).

By the mid i930’s, with the advent of the CCC, fire tools began to proliferate, and the USDA Forest Service sought to standardize tools rather than develop new ones. It was at an equipment standardization conference at Spokane in 1936 that the pulaski tool was proposed for national distribution. The conference instructed the USDA Forest Service’s Region I to develop and further test a prototype suitable for servicewide use (6, 8).

Since “Big Ed’s” day the pulaski, as well as other fire tools, has undergone continual improvement. Pulaski development is an ongoing effort at the USDA Forest Service’s Missoula Equipment Development Center. Careful engineering study, design, and testing have resulted in standards of shape, weight, balance, and quality (fig. I).

Although Ed Pulaski may not have invented the first fire tool put into general use or even first thought of the tool that bears his name, he did develop, improve, and popularize the pulaski. The General Services Administration now puts out bids for more than 35,000 new pulaskis each year — a long way from the prototype so laboriously made in Ranger Pulaski’s home blacksmith shop (1).

—–

Literature Cited

1. Daffern, Jerry. Fire suppression equipment from GSA. Fire Management. 36(2):3–4-; 1975.

2. Gisbom, H.T. Forest fire-a mother of invention. American Forests and Forest Life. 32(389);265-268; 1926.

3. Goodwin, David P. The evolution of firefighting equipment. American Forests. 45(4);205-207; 1939.

4. Graves, Henry S. Protecting the forest from fire. Forest Service Bulletin. 82; 1910. 48 p.

5. Huh, Ruby E. How the pulaski became a popular tool. The Regional Forest Ranger-Part Four. Article on file: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington Office, History Section.

6. Lowden, Merle S. Equipment development and fire research. Fire Control Notes. 19(4);127-129; 1958.

7. Osborne, W.B., Jr. Fire protection equipment accomplishments and needs. Journal of Forestry. 29(8): 1195-1201; 1931.

8. Pyne, Stephen J. Fire in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1982. 654 p.

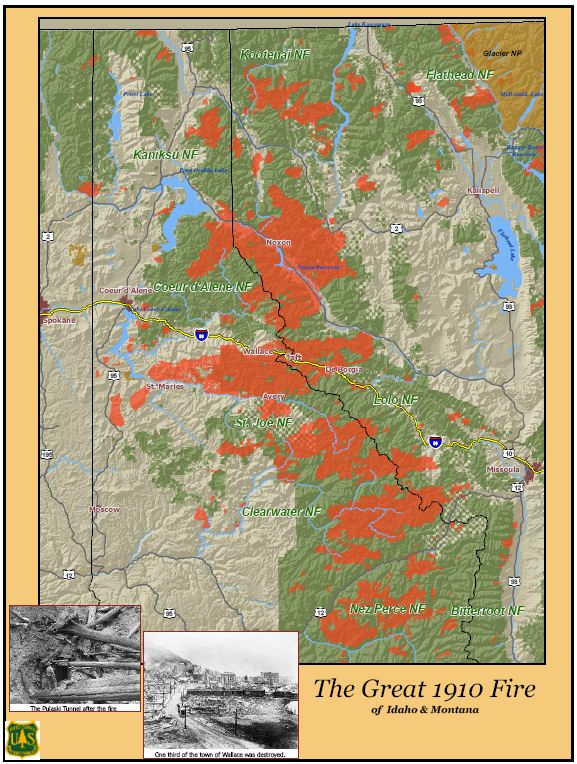

It was not part of the 1986 article, but here is a map showing the location of some of the large fires of 1910.

Nice article pulling together all of the legends and facts of Ed Pulaski and the Pulaski. Check out Ray Kresek’s ‘Fire Lookout Museum’ in Spokane, WA. In addition to having the only museum dedicated to Fire Lookouts Ray has a huge collection of firefighting tools and gear including a large assortment of unusual versions of Pulaskis.

http://www.firelookouts.com/museum.html

Thanks for posting the story (article). I had read about the mine and Pulaski before. Spent many hours using the tool on fires.

Awesome tool.

The Pulaski was always my tool of choice. The shovel is somewhat limited in its use but quite effective at hurling soil and scraping and, when properly sharpened, I recall using it as an axe on small diameters. Do you recall throwing soil with your Pulaski? That sucked. And the brush hook? The epitome of hand tools by my reckoning. Skill and finesse are required limiting my use there!

Anybody recall Pulaski throwing during lulls in tall timber? Certainly more difficult than tossing a double- bitted axe particularly if you wanted a good “stick”. Of course the risk of breaking your handle was ever-present. With a spate of broken handles, Pulaski throwing would be “outed” and threats by overhead down the chain of command would put the kibosh on the “sport”! LR

Great history!