British Columbia must adapt its forest management practices to prepare for future seasons, according to a report by Brenna Owen for The Canadian Press published by the CBC News.

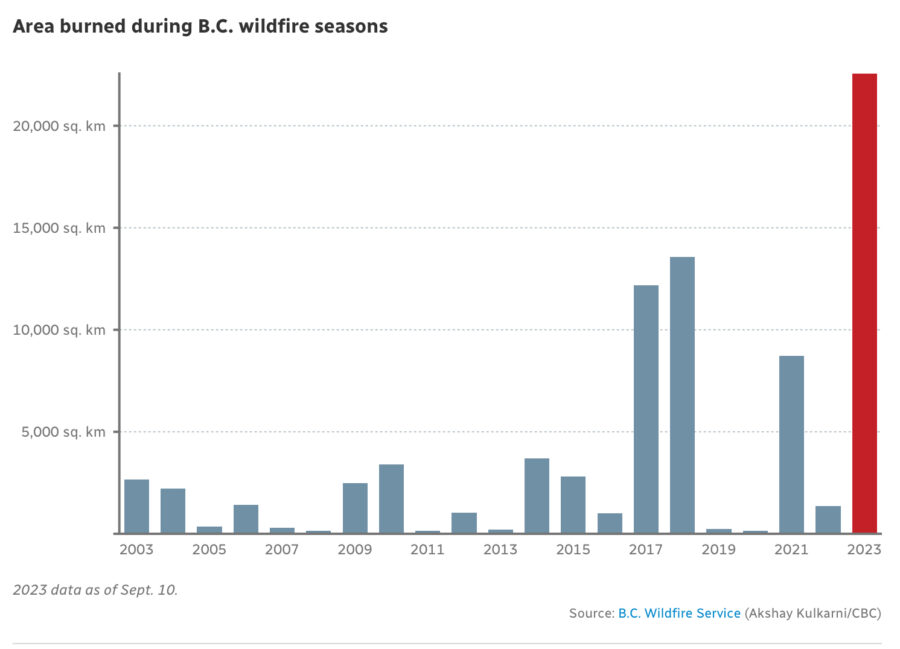

The era of severe record-breaking wildfires has occurred earlier in British Columbia than previous research had projected, and experts say the disastrous 2023 season must serve as a springboard for action.

The surge stems from a combination of climate change and entrenched forest management practices, which have together created a landscape conducive to large, high-intensity blazes, says Lori Daniels, a professor in the department of forest and conservation sciences at the University of British Columbia.

“Society is already paying a huge cost for these climate change-fueled fires,” she says.

“The thing we can control in the short term is the vulnerability of the landscape,” adds Daniels.

Reducing that vulnerability means transforming how the landscape is managed. Shifting away from a timber-focused approach that prioritized conifer stocks over less-flammable broadleaf trees and ramping up prescribed burning are key to protecting communities and supporting healthy, resilient forests, says Daniels.

“The sooner we do it, the better,” she adds.

Daniels is the co-author of a recent paper published by the peer-reviewed journal Nature that examined data from the last century and found an “abrupt” uptick in wildfire activity in B.C. corresponding with a warming and drying trend that began in the mid-2000s.

The province has experienced its four most severe wildfire seasons on record during the past seven years, in 2017, 2018, 2021 and 2023.

“To have four of these seasons out of the last seven is shocking,” she says.

Pine beetle infestations and expanding interface also factors: As development expands farther into the wildland/urban interface, summers in B.C. are increasingly characterized by hot, dry, and windy conditions primed for fires to burn with the speed and intensity that can overwhelm suppression efforts.

Marc-André Parisien, an Edmonton-based research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service, led the study. He underscores the significance of increasing fire intensity.

“If a fire comes in rolling as a 30-metre wall of flames, there’s not a lot you can do,” he says. “You can dump a lot of water on it, but it amounts to spitting on a campfire.”

Ok, maybe let us know how many fire fighters in B.C. Have been caught in a burn over compared to in the U.S. ? I am sure that if they we’re having a problem with losing fire fighters to burn overs or personnel getting skin grafts because there sleeves are rolled up, that they would have new policy.

In the opening of the second YouTube video, I noticed that the B.C. Fire Fighters were marching toward a fire with their sleeves neatly rolled up in a cuff on their biceps.

This was imbedded in the Vernon B.C. newspaper: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziTyxF8-g8g

I was aghast that the firefighters were working in close proximity to

active fire and were doing burnouts whilst their sleeves were also rolled

up. This is on top of the fact that they do not carry fire shelters.

I am a retired fire fighter in central WA. We’ve discussed the B.C. fire service not using shelters. The rationale was that they wouldn’t go to or be placed into dangerous fire situations if they didn’t have shelters. Well, this YouTube video puts that theory to rest.