September 26-Oct. 3 1970: The Laguna fire burned 175,425 acres, killed eight civilians, and destroyed 382 homes. In 24 hours the fire burned from near Mount Laguna, California into the outskirts of El Cajon and Spring Valley. Previously known as the Kitchen Creek Fire and the Boulder Oaks Fire, it was, at its time, the second largest fire in the recorded history of California.

The Laguna fire started from downed power lines during Santa Ana winds near the intersection of Kitchen Creek road and the Sunrise Highway in the Laguna Mountains in eastern San Diego County on the morning of September 26, 1970. In only 24 hours it burned westward about 30 miles (50 km) to the west. The fire devastated the communities of Harbison Canyon and Crest. Santa Ana winds are warm, dry winds that characteristically occur in Southern California weather during autumn and early winter.

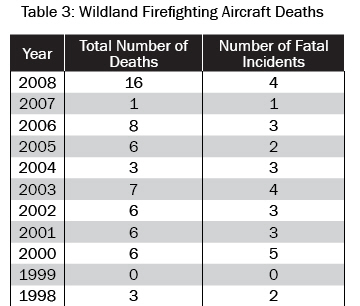

Here is one of the pages from the report referenced below. Anyone remember when we used to make charts and graphs using colored pencils and graph paper?

=======================

For more info:

http://www.wildfirelessons.net/documents/Laguna_Fire_Analysis_1970.pdf

The day the Laguna fire started I was a crewmember on the El Cariso Hot Shots, and we were mopping up a brush fire near Corona. We heard the radio traffic that morning about the new fire and the reports that it was was cranking. It was The Big One. And there we were, stuck on the dreaded mopup on a fire that was pretty much out. For hours we kept poking around trying to find something hot to put out, as we kept hearing more about the fire on Laguna Mountain that was hauling ass. We wanted to be there.

Finally, late in the afternoon we were dispatched to it. By the time we got to Pine Valley it was after sunset, and for some reason, I, a first-year hot shot, was in the pickup with Ron Campbell, the Superintendent. The two open-top crew carriers were behind us. As we drove into Pine Valley the hills to the south and east were alive with the orange flames of the fire. The one radio channel we had on the Cleveland National Forest was completely jam-packed with radio traffic. You could not get a word in edgewise. We knew that this was going to be one that we would remember.

We worked on the fire all that night and then pulled several more shifts before we were transferred to the Boulder 2 fire in Cuyamaca State Park, which was a rekindle from the Boulder fire.