A CAL FIRE firefighter who died July 28, 2019 in San Diego County died of a heat exposure, reports NBC San Diego.

Yaroslav Katkov, 28, collapsed during his second attempt at a 1.45-mile training hike near the De Luz Fire Station while wearing full gear and carrying 20 to 30 pounds of weights, according to an autopsy.

He was flown in an air ambulance to Temecula Hospital but suffered a two-minute seizure while en route. When he was admitted, his body temperature was 107.4 degrees. Fifteen hours later he was pronounced dead.

CAL FIRE’s preliminary report on the incident, the “Green Sheet”, said the three-person crew began a physical training hike at 8:40 a.m. with the expectation that they would finish within the 30-minute time limit. Mr. Katkov struggled, stopping multiple times, completing the hike in 40 minutes. After a 20-minute break to rehydrate, the Captain had the crew repeat the hike at 9:40 a.m.

NBC San Diego described what occurred on the second hike:

Katkov took more than 20 breaks along the trail which were documented by the captain, the report said. About halfway through the trail, the second firefighter noticed Katkov stumbling and losing his balance. He was told to hike directly behind Katkov and hold onto him so that he didn’t fall off the trail.

As they approached a ridge, the firefighter had to push Katkov’s back to help him get over. Once Katkov did, he fell forward and sat down. Katkov was then told to remove some of his gear so that he could cool down but was unable to, the report said.

More gear was taken off, and water was poured over Katkov’s head. At around 10:38 a.m. when the fire captain noticed Katkov’s mental status declining, he called for an air ambulance rescue.

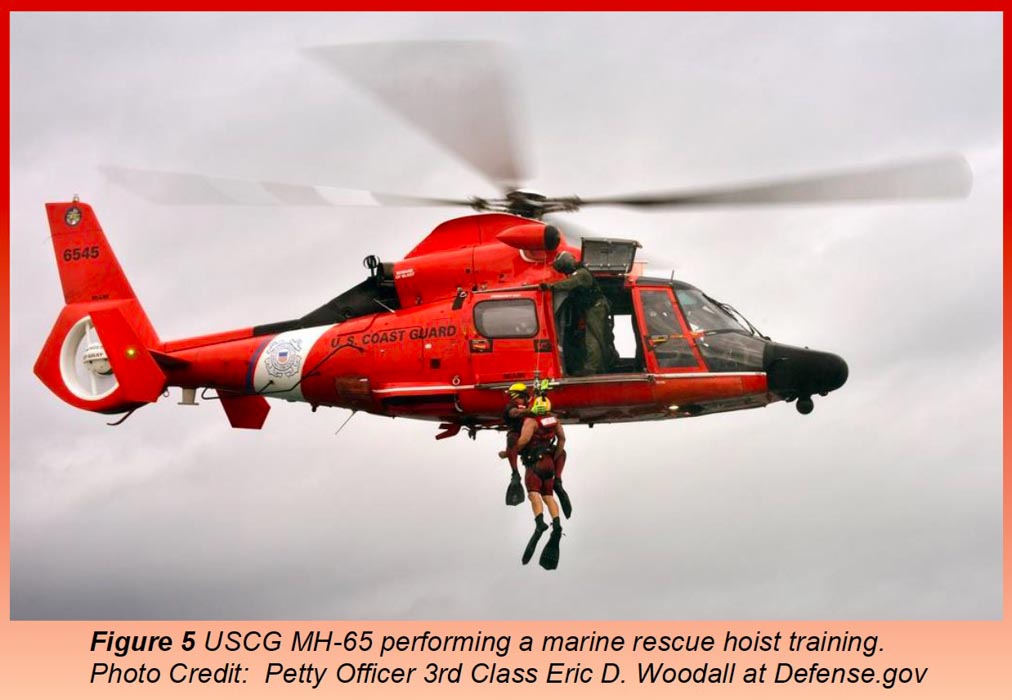

Cal Fire’s helicopter arrived over Katkov and the crew at approximately 11:19 a.m. and Katkov was hoisted from below, according to the report. About 15 minutes later, the Cal Fire [helicopter] dropped Katkov off at a site where a Mercy air ambulance was waiting to transport Katkov to the hospital.

The second helicopter took off with Katkov inside at around 12:04 p.m., about an hour-and-a-half after the fire captain called for emergency assistance. On the way to the hospital Katkov was unresponsive but breathing, according to the report.

KNTV reported that Mr. Katkov was flown to Temecula Valley Hospital. Google Maps shows it would take an estimated 31 minutes to drive from De Luz Station to Temecula Valley Hospital, part of the time on curvy county roads. Based on that, we can assume it would take no more than 10 minutes for the Mercy air ambulance to arrive at the hospital — at about 12:14 p.m. This was approximately one hour and 36 minutes after the request for extraction by helicopter. Presumably the incident occurred in a remote area inaccessible by ground ambulance. It is likely that the medical crew on the Mercy helicopter began treatment of the patient as soon as he arrived at their location during the 30 minutes before the helicopter took off.

Estimated time line:

10:38 a.m. — Air ambulance rescue requested

11:19 a.m. — CAL FIRE/San Diego Sheriff Dept. helicopter arrives at scene

11:34 a.m. — (Approximate time) The CAL Fire helicopter delivered Mr. Katov to Mercy Air ambulance

12:04 p.m. — Mercy air ambulance departs for Temecula Valley Hospital

12:14 p.m. — (Approximate time) Mercy air ambulance arrives at hospital.

(UPDATE September 28, 2019: here is a link to the CAL FIRE “Green Sheet”.)