A new study conducted in Scotland found that fighting fires could increase the risk of a heart attack.

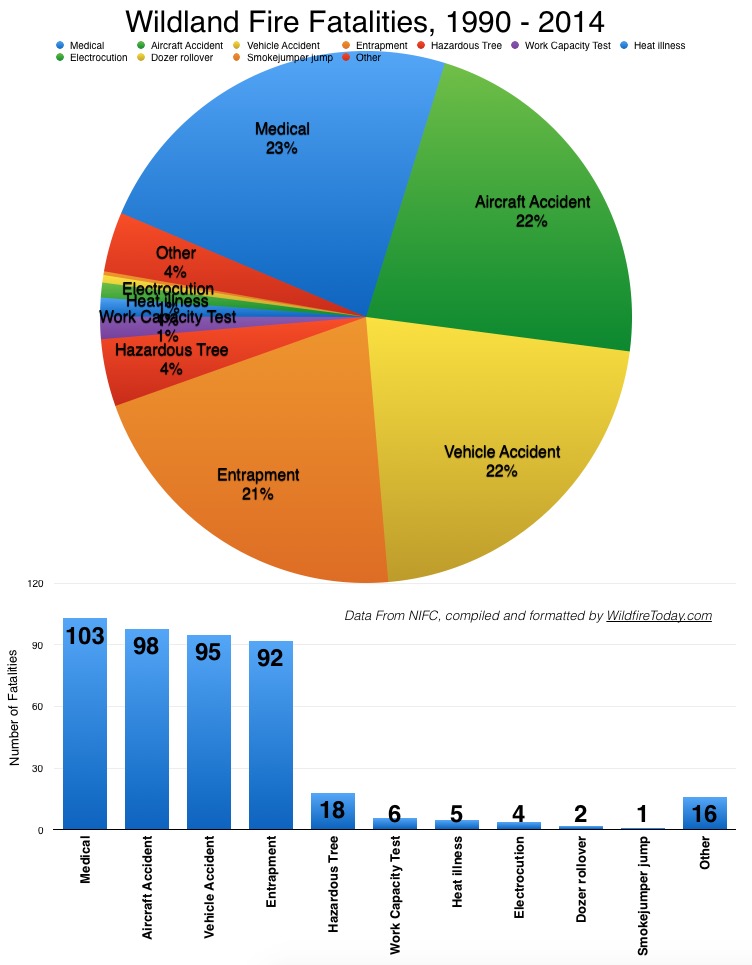

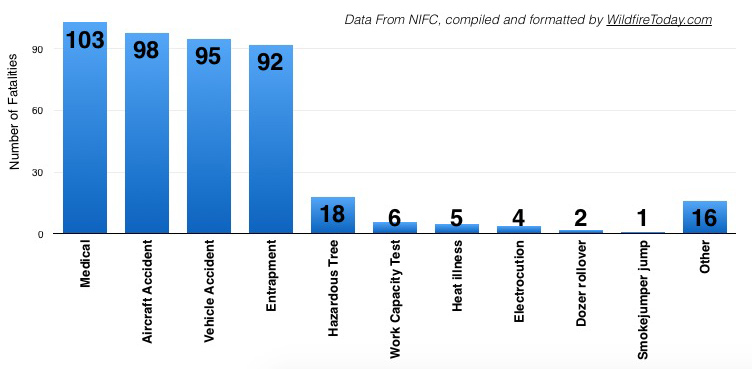

Wildland firefighter fatality data collected by the National Interagency Fire Center from 1990 to 2014 shows that most of the deaths in that period were caused by medical issues (primarily heart related). The top four categories which account for a total of 88 percent are, in decreasing order, medical issues, aircraft accidents, vehicle accidents, and entrapments. The numbers for those four are remarkably similar, ranging from 23 to 21 percent of the total.

The new UK study suggests that exposure to heat and the physical exertion required to control a fire can cause firefighter’s blood to clot and is putting firefighters at risk of heart attack.

Physical analysis of 19 firefighters in Scotland also found that tackling blazes put a strain on their hearts and worsened the functioning of their blood vessels.

Previous work has shown that firefighters have the highest risk of heart attack of all the emergency services.

The new study reported that a heart attack is the leading cause of death for on-duty firefighters and they tend to suffer cardiac arrests at a younger age than the general population.

Nationwide in the US, around 45% of on-duty deaths each year among firefighters are due heart issues, and researchers at the British Heart Foundation (BHF) and Edinburgh University believe the situation in the UK is comparable, although they did not know the cause.

On two occasions, at least one week apart, they either performed a mock rescue from a two-storey building for 20 minutes or undertook light duties, in the case of the control group, for 20 minutes.

The firefighters wore heart monitors that continuously assessed their heart rate and its electrical activity.

Blood samples were also taken before and after, including measurement of a protein called troponin that is released from the heart muscle when it is damaged.

Those taking part in the rescue had core body temperatures that rose by 1C and stayed that way for three or four hours.

There was also some weight loss among this group, while their blood vessels also failed to relax in response to medication.

Their blood became “stickier” and was more than 66% more likely to form potentially harmful clots than the blood of people in the control group.

Dr Mike Knapton, associate medical director at the BHF, said: “Firefighters routinely risk their lives to save members of the public. The least we can do is make sure we are protecting their hearts during the course of their duties.”

****

Below is a representation of the wildland firefighter data from NIFC, compiled by Wildfire Today.