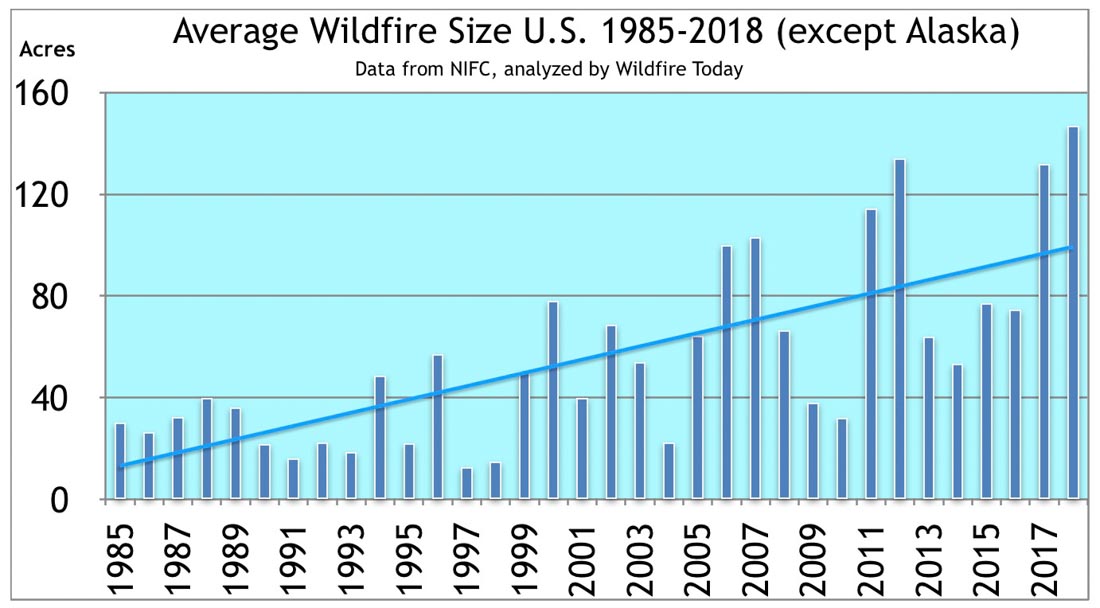

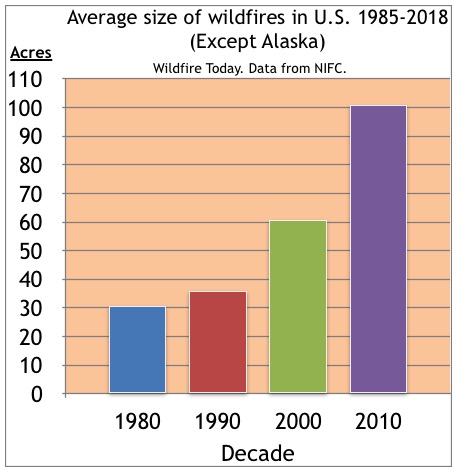

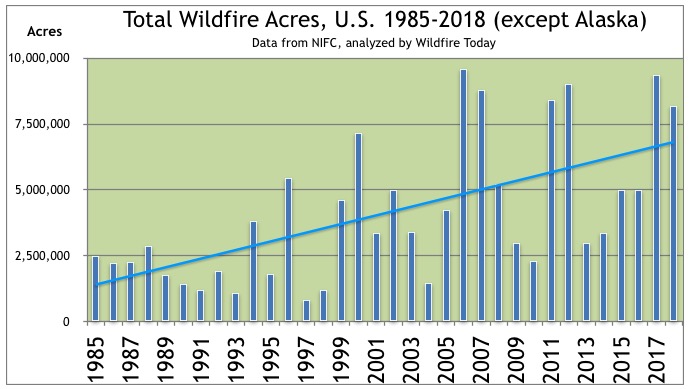

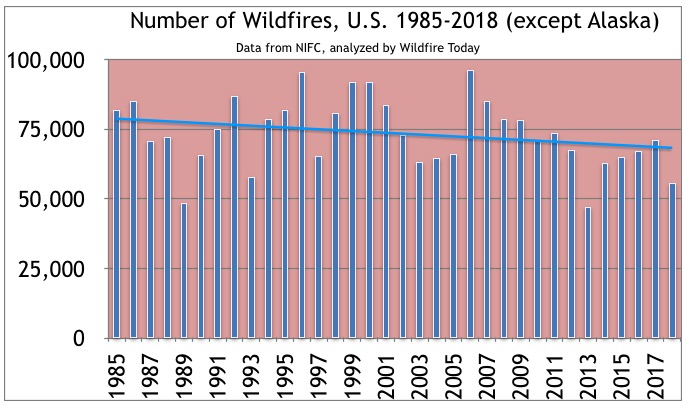

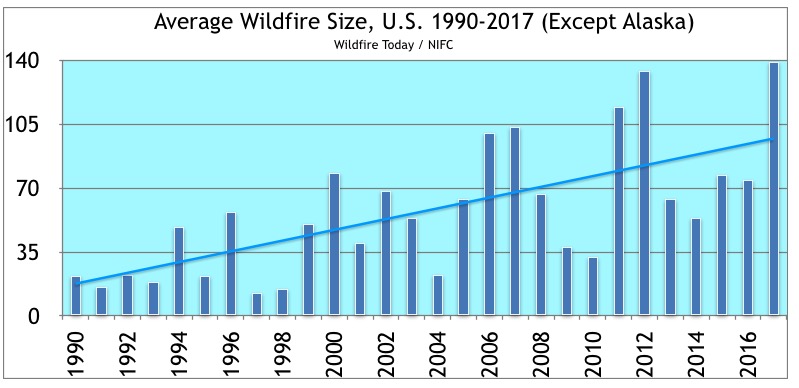

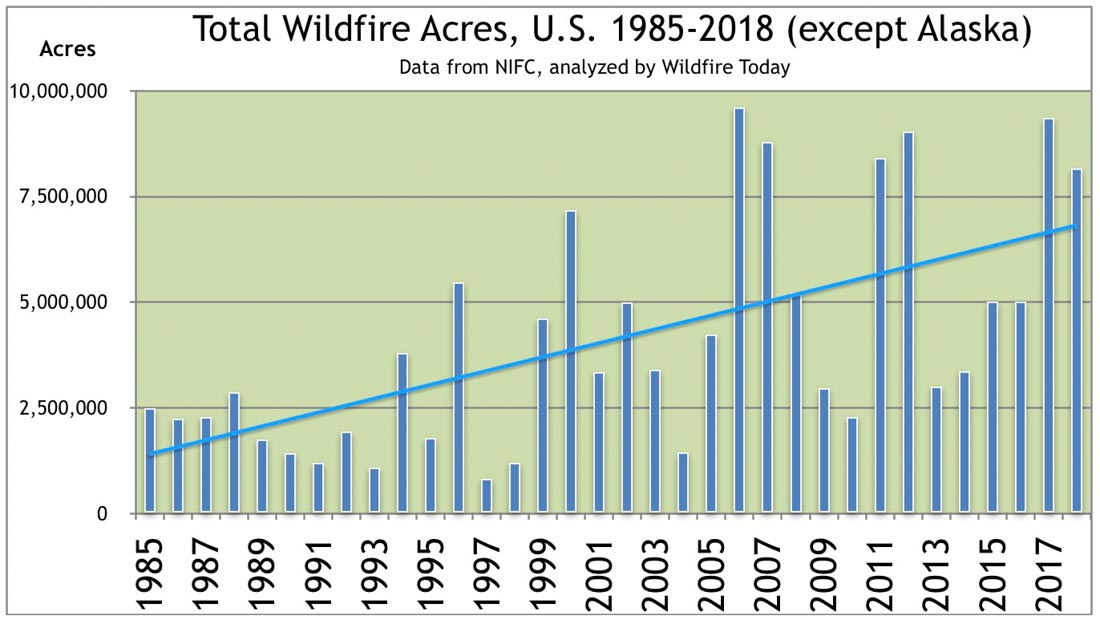

The use of Area Command Teams has been declining in recent years in spite of the trend of more acres burned nationwide and increasing average size.

The use of Area Command Teams has been declining in recent years in spite of the trend of more acres burned nationwide and increasing average size.

In two of the last three years, 2016 and 2018, there were no assignments for Area Command Teams. In 2017 there were a total of five: Joe Stutler-2, Tim Sexton-1, and Rowdy Muir-2. The number of ACTs was reduced from four to three in 2015.

The National Multiagency Coordinating Group (NMAC) which manages the ACTs, is concerned that if the teams do not receive assignments some individuals on the teams may lose currency in 2020.

Below is an excerpt from a letter sent by the NMAC on May 17, 2019 to Federal and State Agency Administrators:

NMAC is requesting your support with maintaining currency of the three federally sponsored Area Command Teams (ACT). These teams are a valuable part of our large fire management organization and have been underutilized during some of our most complex incident management situations.

Currently, within federal agencies (excluding Coast Guard), there are only three fully qualified Area Commanders (ACDRs) in the system. While the Area Command course, S-620 has been delivered this year, the lack of assignments may cause loss of currency of the ACTs in 2020.

ACTs provide strategic leadership to large theaters of operation while significantly reducing the workload for agency administrators and fire management staff. Common roles of ACTs typically include facilitating Incident Management Team (IMT) transitions, in-briefings, and closeouts. Additionally, ACTs coordinate with agency administrators, fire staffs, geographic areas, and MAC groups on complexity analysis, implementation of objectives and strategies, setting priorities for the allocation of critical resources, and facilitating the effective use of resources within the area.

We are concerned perceptions exist that ACTs can be barriers to direct communications between agencies and IMTs. As agency administrator, through your delegation of authority communicating your expectations to ACDRs, you have the opportunity to determine the role in which ACTs can best serve your needs. ACTs are committed to ensuring enhanced communications between agency administrators, fire managers, and IMTs.

NMAC request the support of agency administrators to exercise current ACTs in 2019 if and when appropriate.

It is surprising how many large complex incidents do not get a chance to benefit from the help that an ACT can provide. Even in 2016 when there were many large fires burning in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and South Carolina at the same time, no ACTs were mobilized. You might wonder if any of the fires, including the one that burned into Gatlinburg, Tennessee, would have turned out differently if there had been a group of highly skilled personnel looking at the big picture, helping to obtain resources, analyzing the weather forecast, and utilizing short and long range fire behavior predictions.

An ACT may be used to oversee the management of large incidents or those to which multiple Incident Management Teams have been assigned. They can take some of the workload off the local administrative unit when they have multiple incidents going at the same time. Your typical Forest or Park is not usually staffed to supervise two or more Incident Management Teams fighting fire in their area. An ACT can provide decision support to Multi-Agency Coordination Groups for allocating scarce resources and help mitigate the span of control for the local Agency Administrator. They also ensure that incidents are properly managed, coordinate team transitions, and evaluate Incident Management Teams.

National ACTs are comprised of the following:

- Area Commander (ACDR);

- Assistant Area Commander, Planning (AAPC);

- Assistant Area Commander, Logistics (AALC);

- Area Command Aviation Coordinator (ACAC); and

- Two trainees.

They usually have an additional 2 to 15 specialists, including Fire Information, Situation Unit Leader, Resource Unit Leader, and sometimes others such as Safety, Long Term Planning, or assistants in Planning, Logistics, or Aviation.