Above: Smoky conditions on the Legion Lake Fire in Custer State Park in South Dakota, December 12, 2017. Photo by Bill Gabbert.

Originally published at 6:02 p.m. MT, February 6, 2018.

After collecting data from wildland firefighters in the field, a group of researchers concluded that firefighters’ exposure to smoke can increase the risk of mortality from lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, and cardiovascular disease. In this first section we cover what is in vegetation fire smoke, and after that we have details about the additional mortality risk faced by firefighters who can’t help but breathe the toxic substances.

What is in the air that firefighters breathe?

There have been many studies about smoke dating back to the 1988 NIOSH project at the fires in Yellowstone National Park. Most of them confirmed that yes, wildland firefighters ARE exposed to smoke and in most cases they quantified the amount.

In 2004 Timothy E. Reinhardt and Roger D. Ottmar found a witches’ brew of methyl ethyl bad stuff that firefighters are breathing. All of these are hazardous to your health:

- Aldehydes (volatile organic compounds); can cause immediate irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, and inhalation can cause inflammation of the lungs. Short-term effects include cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain. The most abundant aldehyde in smoke is formaldehyde. When formaldehyde enters the body, it is converted to formic acid, which also is toxic.

- Sulfur dioxide (SO²); causes severe irritation of the eyes, skin, upper respiratory tract, and mucous membranes, and also can cause bronchoconstriction. It forms sulfuric acid in the presence of water vapor and has been shown to damage the airways of humans.

- Carbon monoxide (CO); As CO is inhaled it displaces O2 as it attaches to red blood cells and forms COHb. COHb reduces the ability of the blood to carry oxygen and causes hypoxia (a condition in which the body does not receive sufficient oxygen). Due to their strenuous work, wildland firefighters often have increased respiratory rates, which will increase the amount of CO being inhaled when smoke is present. COHb has a half-life (the time it takes half of the COHb to dissipate from the body) of about 5 hours. Symptoms of CO exposure include headaches, dizziness, nausea, loss of mental acuity, and fatigue. Prolonged, high exposure can cause confusion and loss of consciousness

- Particulate matter; Respirable particulates are a major concern as they can be inhaled into the deeper recesses of the lungs, the alveolar region. These particles carry absorbed and condensed toxicants into the lungs

- Acrolein; may increase the possibility of respiratory infections. It can cause irritation of the nose, throat, and lungs. Long-term effects can include chronic respiratory irritation and permanent loss of lung function if exposure occurs over many years.

- Benzene; can cause headaches, dizziness, nausea, confusion, and respiratory tract irritation. Although the human body can often recover and repair damage caused by irritants, prolonged exposure from extended work shifts and poorly ventilated fire camps can overwhelm the ability to repair damage to genes and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

- Crystalline silica; can cause silicosis, a noncancerous lung disease that affects lung function. But OSHA classifies it as a carcinogen.

- Intermediate chemicals; have been shown to cause a variety of health problems including bronchopulmonary carcinogenesis, fibrogenesis, pulmonary injury, respiratory distress, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and inflammation.

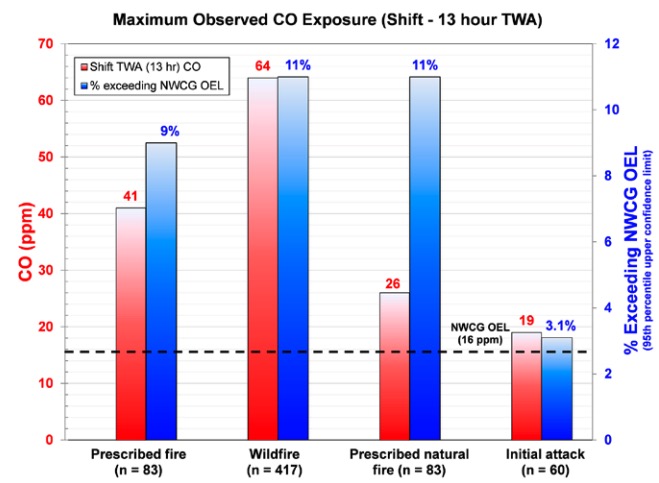

One of the more recent research efforts, from 2009 to 2012, was led by George Broyles of the U.S. Forest Service, National Technology and Development Program, in Boise, Idaho. They collected data in 11 fuel models in 17 states on initial attack, prescribed burns, and large project fires. The group measured carbon monoxide (CO) with electronic datalogging dosimeters and particulate matter using air pumps and filters.

Monitoring carbon monoxide (CO) can be important, and is also fairly easy to do and not terribly expensive. Researchers have found that it can be a surrogate for the primary irritants of concern in wildland smoke near the combustion source. If CO is present, it’s almost certain that the smorgasbord of nasty stuff is in the air.

Electronic CO monitors are available for $100 to $300. Another option is the little disposable CO monitors called diffusion tubes. With the holder they are about the size of a dry erase marker. Many are made by Drager, and for eight hours can record the cumulative CO. You can’t get an instantaneous reading, but the total hourly exposure can be monitored. They cost about $13 each. If one or two people on the crew carry them it can provide a heads up if the air quality is really bad.

What are the health effects of smoke exposure on a wildland fire?

Employers in most if not all workplaces are required to minimize hazards and provide a safe working environment. But of course it is impossible to totally eliminate all risks to firefighters. A cynic might assume that leadership in the wildland fire community may be hesitant to ask the question if they don’t want to hear the answer.

In spite of numerous studies confirming that yes, there is smoke where wildland firefighters work, there has been little in the literature that quantifies the effects on a person’s health. A new study published in August, 2017 contains a preliminary analysis addressing that question.

It is titled Wildland Fire Smoke Health Effects on Wildland Firefighters and the Public – Final Report to the Joint Fire Science Program. The authors are Joe Domitrovich, George Broyles, Roger D. Ottmar, Timothy E. Reinhardt, Luke P. Naeher, Michael T. Kleinman, Kathleen M. Navarro, Christopher E. Mackay, and Olorunfemi Adetona.

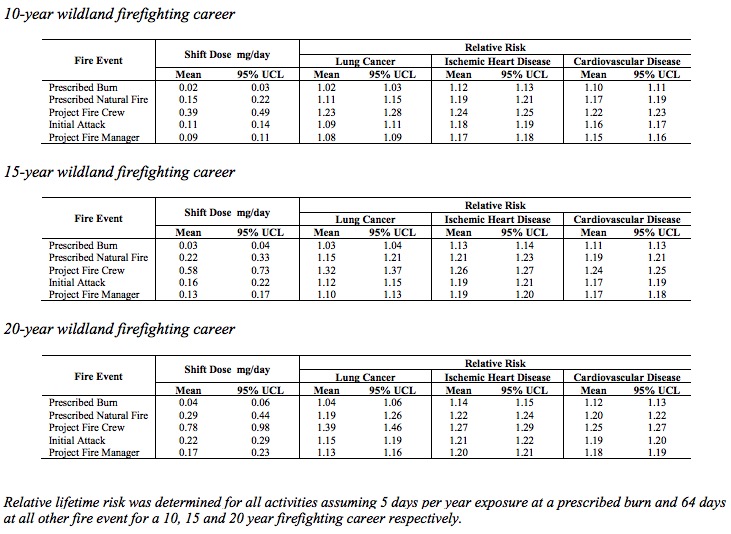

They used the field data collected in the 2009 to 2012 George Broyles study to extrapolate the physical and health effects on humans. The authors actually came up with numbers that indicate firefighters’ relative mortality risk for lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, and cardiovascular disease.

They estimate that after a 10-year career with a project fire crew a firefighter would have a 22 to 24 percent increase in mortality from those three diseases, compared to a person with no smoke exposure. After 20 years the risk is 25 to 39 percent. The risks are lower for those working in environments found at prescribed burns and initial attack.

One of the authors of the study, Kathleen Navarro, told us the data should be considered preliminary. She continues to analyze their findings and may fine tune their conclusions later.

In the video below Ms. Navarro talks about collecting data in the wildland firefighting environment.

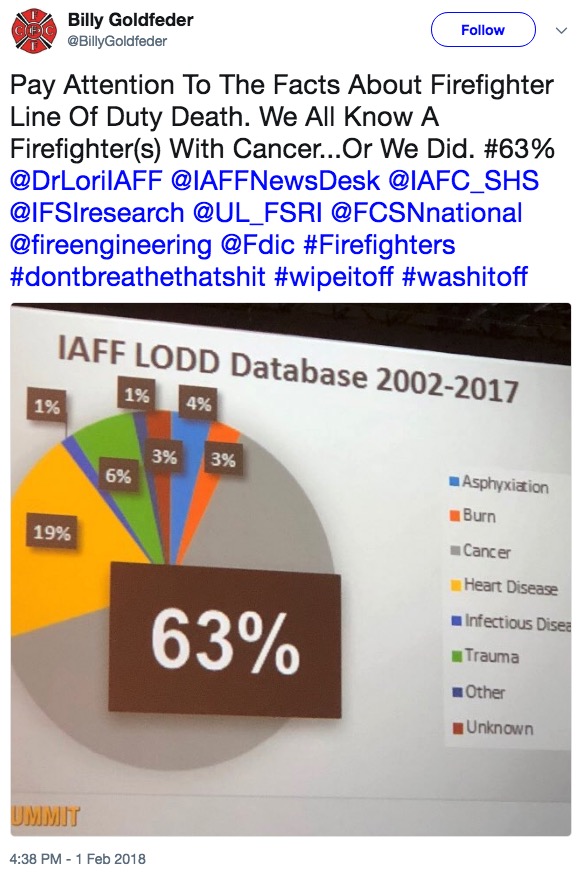

Presumably the International Association of Fire Fighters data below, primarily represents structural firefighters. It appears to show that 63 percent of firefighter line of duty deaths are from cancer.

The 2017 study summarized the recommendations that have been made by researchers over the last 25 years about how to reduce smoke exposure:

- Minimize mopup.

- Develop a medical surveillance program.

- Develop wildland fire-specific Occupational Exposure Limits.

- Train firefighters on smoke hazards.

- Reduce exposure by limiting shift length.

- Rotate crews out of heavy smoke areas.

In 2012 the National Wildfire Coordinating Group issued Guidance for Monitoring and Mitigating Exposure to Carbon Monoxide and Particulates at Incident Base Camps. The group established a new standard for carbon monoxide for wildland firefighters:

Based on the best available science to date, the Smoke Exposure Task Group (SETG) and their group of leading researchers from across the United States established an exposure recommendation for wildland fireline operations to be: Carbon monoxide of 8 ppm for a 24 hour period, and 16 ppm for a 13 hour work shift.

We checked with the U.S. Forest Service, asking about their views on the effects of smoke and the long term plans on the subject.

“The health and safety of wildland firefighters is the top priority of the USDA Forest Service in wildland fire management,” said Shawna Legarza, Director, Fire and Aviation Management, USDA Forest Service. “The agency has been working for several years with leading experts across the country to understand and further study the short and long term impacts of wildland fire smoke on firefighter health. The USDA Forest Service has guidelines in place to reduce the exposure of wildland firefighters to smoke on the fireline. Once this [2017] study is peer reviewed and a final report is published, we will review it carefully and determine measures that are needed to implement the findings.”

What should be next?

Now that we have at least some pretty good data about what firefighters are breathing on wildland fires and information about increased mortality caused by the carcinogens, what is the next step?

Long term firefighter health tracking

In order to fix or improve a situation it has to be defined. It is difficult to say firefighters’ health is a serious problem unless the short and long-term health of firefighters is tracked. There is no national registry that tracks their exposure or health during and after their careers. Two bills introduced in Congress since 2016 have failed to gather any traction. With the track record of Congress over the last five to 10 years, we should assume there will be no national registry in our lifetimes. This means there needs to be action taken at the state, local, or national agency levels.

And of course the National Wildfire Coordinating Group should, by definition, COORDINATE this effort.

Firefighting leaders need to step up and lead from the front. Let’s see who will be first.

Presumptive illnesses

All fire departments as well as state and federal agencies that employ firefighters or “forestry technicians” must establish a system of presumptive illnesses. If a firefighter is diagnosed with a condition that is on the list, they will be presumed to have contracted the illness on the job, and would be covered like any other on the job injury. The British Columbia government recognizes at least nine “presumptive cancers” among firefighters, including leukemia, testicular cancer, lung cancer, brain cancer, bladder cancer, ureter cancer, colorectal cancer, and non-Hodgkins’s lymphoma.

Read more about smoke research.

Thanks Bill. Your listing of six recommendations says about all anyone needs to know about this subject. George Broyles listed them in his study from 2013, noting no progress seems to have occurred in two plus decades. NTDC is doing great work and moving forward on recommendations 2 and 3. The sad part is zero movement on 1 and 4. There is plenty of science to justify these recommendations, yet no implementation of note, only calls for further research.

Smoke exposure needs to be given more emphasis in the planning process on incidents. The the risk analysis process and the document 215a often mention limit exposure to smoke. But what is actually done to limit this smoke exposure. The techniques for limiting this exposure need to have more emphasis during training. Needs to be included in delegations of authority and training for line officers. A good place to gather ideas for limiting smoke exposure would be from the IHCs and ICS after season AARs.

Ken,

I agree that smoke exposure should be emphasized in the 215A and in. The risk analysis of any operation.

Real time monitoring by line medics using RAD57 carboxyhemoglobin monitors can detect CO exposure to document TWA’s / PEL’s / and IDLH atmospheres. HCN poisoning should also be considered in the urban-interface settings or roadside wildland fires where plastics and styrene may be involved.

Of more concern is the data from the structural fire world on the absorption of carcinogens from areas such as the neck, armpits, groin, and other areas in which sweat glands can cause increased mobilization of carcinogens through skin pores into the blood and lymphatic circulation.

More shower units should be deployed and shorter shiftsto allow firefighter to clean their skin of contaminants. A standard of laundry services and requirement to launder or exchange PPE on a frequent basis.

The 16 hour work day is no longer reasonable. More needs to be done to allow for decontamination and reduction of exposure to reduce frequency and severity of the consequence of firefighting.

I am happy to see some comprehensive studies on long term smoke exposure. When I stared in the 80’s it was a much different attitude about exposure to smoke and other toxins. Anyone who’s been around awhile knows many firefighters who’ve been affected. Would I have changed my career path if at the time I was aware? No. But I have had long talks with the wife about the health affects after all these years as a Shot.

One way we can track wildland firefighter smoke exposure is through their IQCS records. Are some fuel types more toxic then others?

I would like a copy of this report in full

Thanks

Rob, there is a link to it in the article above.

My son was a wildfire fighter. He died 9 months ago from lymphoma and sarcoma at age 41. So very sad. He had 3 children ad a wife who miss him terribly also. Thanks for bringing this out in the open. Sophia, Jeremiah’s mom.

My son was a wildfire fighter. He died 9 months ago from leukemia and sarcoma at age 41. So very sad. He had 3 children ad a wife who miss him terribly also. Thanks for bringing this out in the open. Sophia, Jeremiah’s mom.

Sophia, I am very sorry for your loss. Thank you for sharing your story.

Sorry. Mistyped….. It was lymphoma,not leukemia.

Just wanted to be clear that the legislation establishing certain presumptive illnesses for firefighters in British Columbia does not cover wildland firefighters. Workers exposed to the hazards of a forest fire scene are specifically excluded. The union representing wildland firefighters in BC continues to work to convince the provincial government in BC to extend this coverage to wildland firefighters.

Thanks Megan.

So I have long tried to get the EPA to research and publish the health consequences and cost of exposing large populations to the USFS use of fire to burn slash piles from logging operations billed as fire mitigation operations. Really? And the burning operations gone wild. And the smoke from field burning. There is scant scientific research into the health-cost- benefit versus the “savings” from all the burning. Wildfire smoke season is now a 3/4 of the year “season”. And firefighters have to be deployed to every burn. These strong young people do not know the health risks which are unreported and I researched.