The article below was written by John N. Maclean and Holly Neill.

****

The Wall Street Journal and Fire

By John Maclean and Holly Neill

Kyle Dickman’s new book, On the Burning Edge, about hotshot culture and the Yarnell Hill Fire, has been reviewed in the Saturday, May 23, edition of the Wall Street Journal by Mark Yost, who is identified as a firefighter and paramedic from Highwood, Illinois. The review makes a number of errors and misleading assertions about fire policy and the Yarnell Hill Fire independent of the material in Dickman’s book. Journal reviews receive respectful attention, but the review is wrong on so many points that it should be answered in a timely fashion–Maclean is preparing a review of Dickman’s book for the Journal of Forestry, but that won’t appear for several months.

Yost writes: “The policy of letting low burns do their work was in place until the 1980s, when environmentalists began lobbying for letting underbrush and tracts of forest go uncut, unmanaged and uncleared by small fires. The result was denser forests and forest beds of virtual kindling.”

Response: As every student of wildfire knows, after the Big Burn of 1910 the Forest Service developed a policy, in force for many decades, to put out all fires by 10 AM the morning after they were spotted.

Yost writes: “The Yarnell assignment came on a Sunday, normally a day off for the crew. The fire, started by lightning the day before…”

Response: The fire was started Friday, June 28, 2013, two days before the fatalities occurred on Sunday.

Yost writes: “When the Granite Mountain crew arrived, the flames were closing in on the small town of Yarnell.”

Response: When the Granite Mountain crew arrived on Sunday morning, the flames, which were far from Yarnell, were headed north and away from the town, toward Peeples Valley.

Yost writes that the lookout, Brendan McDonough, was in his fourth season.

Response: McDonough was in the beginning of his third season.

Yost writes that when the fire turned toward Yarnell, in the afternoon, McDonough “was no longer in a position to see what was going on and warn his crewmates.”

Response: McDonough reported to Jesse Steed, acting Granite Mountain Superintendent (normally assistant superintendent) that he could see that the fire had reached his trigger point and he was departing, which he did. At that point, photo and other evidence proves that Steed and the other hotshots could see exactly what the fire was doing.

Yost writes that Eric Marsh, (normally the superintendent of the Granite Mountain Hotshots), was “attached to the command staff on the day of the Yarnell fire, he was at first stationed in a makeshift outpost along a highway.”

Response: Marsh was never stationed at a makeshift outpost. He led the crew to the fire by scouting ahead and flagging an upward route. As far as being “attached to the command staff,” Marsh was made division Alpha supervisor and performed that duty in the field.

Yost writes: “The Granite Mountain crew had left the black and were working on the side of a hill, a dangerous position, Mr. Dickman explains, because it put them in danger of the fire coming down on top of them.

Response: The hotshots were digging direct handline, with one foot in the black, on the side of the hill. There was risk of the fire coming up to them from below, not coming down on top of them from the black above.

Yost writes: “Some investigators have speculated that, when the wind reversed, sending flames speeding toward the firefighters, they made a desperate attempt to get to a nearby horse farm and just didn’t make it.”

Response: No serious investigator has made that charge. It is agreed, and supported by photo and recorded radio exchanges as well as interview accounts, that the hotshots deliberately left their position and headed toward the ranch, which was identified as a safety zone. The ranch is not a horse farm: it is owned by Lee and DJ Helm who keep pets, including miniature horses, donkeys and shelter animals.

Yost writes about the fatalities, “In the event, the fire moved so fast that rescuers were able to get to the team within minutes—but too late.”

Response: Firefighters work as crews, not as teams. It took an hour and 43 minutes, or 103 minutes, from the time Eric Marsh said over the radio that the crew was deploying until a medic reached the deployment site, according to official investigation records.

****

The book review in the Wall Street Journal can be seen HERE, but you generally have to be a paid subscriber to view it. However, mobile phone users can sometimes read it without a subscription.

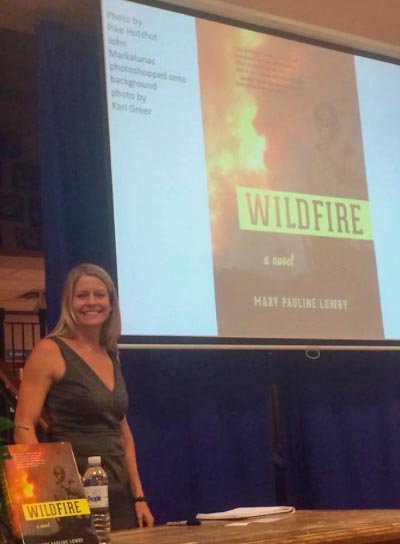

John N. Maclean has written several books about wildland fire, including “Fire on the Mountain”, “Fire and Ashes”, and “The Thirtymile Fire”. His most recent book, “The Esperanza Fire: Arson, Murder and the Agony of Engine 57”, is slated to be made into a movie. Currently he is working on a book about the Yarnell Hill Fire.

Many wildland firefighters live in areas where firewood is available, as long as you have a permit and know how to use a chain saw. The Guardian has an interesting review of a new book about a very old subject, collecting and processing your own firewood.

Many wildland firefighters live in areas where firewood is available, as long as you have a permit and know how to use a chain saw. The Guardian has an interesting review of a new book about a very old subject, collecting and processing your own firewood.