The Colorado Fire Camp sent out a message from their Twitter account to their 101 followers on October 21 which said:

#OSHA vs. wildfire agencies: Safety & Health no longer goal of #NWCG structure, new focus on risk management http://bit.ly/4oy38E 2:50 PM Oct 21st from TweetDeck

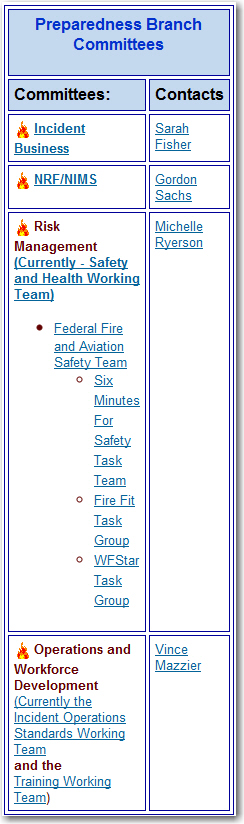

To say that safety and health are no longer goals of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) seemed rather surprising, so I went to the link, which leads to an organization chart showing the Committees of the NWCG.

A portion of the chart is shown here on the right. As you can see, the organization is changing. The “Safety and Health Working Team” is becoming the “Risk Management” committee, and the “Incident Operations Standards Working Team” is merging with the “Training Working Team” to become the “Operations and Workforce Development” committee.

To say that “safety and health is no longer a goal” of the NWCG is misleading at best. And yes, the term “safety” in the organization chart has been replaced with “risk management”. But that does not mean that “safety and health is no longer a goal”.

Here are some definitions of the term “risk management”.

- Risk Management is the identification, assessment, and prioritization of risks followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability and/or impact of unfortunate events. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_management

- The process of determining the maximum acceptable level of overall risk to and from a proposed activity, then using risk assessment techniques to determine the initial level of risk and, if this is excessive, developing a strategy to ameliorate appropriate individual risks until the overall level of risk is reduced to an acceptable level. en.wiktionary.org/wiki/risk_management

- Risk management is the active process of identifying, assessing, communicating and managing the risks facing an organization to ensure that an organization meets its objectives. www.lesrisk.com/glossary.htm

- The technique or profession of assessing, minimizing, and preventing accidental loss to a business, as through the use of insurance, safety measures, etc. Origin: 1960–65. Dictionary.com

I exchanged some email messages with Michelle Ryerson, the fire safety program manager for the Bureau of Land Management, the current chair of the Safety and Health Working Team, and interim chair for the Risk Management Committee. I asked about the reason for the changes and she said the name change better reflects their approach to safe and effective fireline operations. The reorganization of the NWCG gave the groups an opportunity to change the names, encompassing a more comprehensive programmatic approach.

“We are in the process of converting over”, she said, “but have not been officially chartered under the new title of ‘Risk Management Committee’ (mission will remain the same) — plan to have conversion happen early spring of 2010 and will make note of it on our website”.

I asked what the effect of the change would be on firefighters. She responded: Continue reading “"Safety" or "risk management" in wildland fire?”