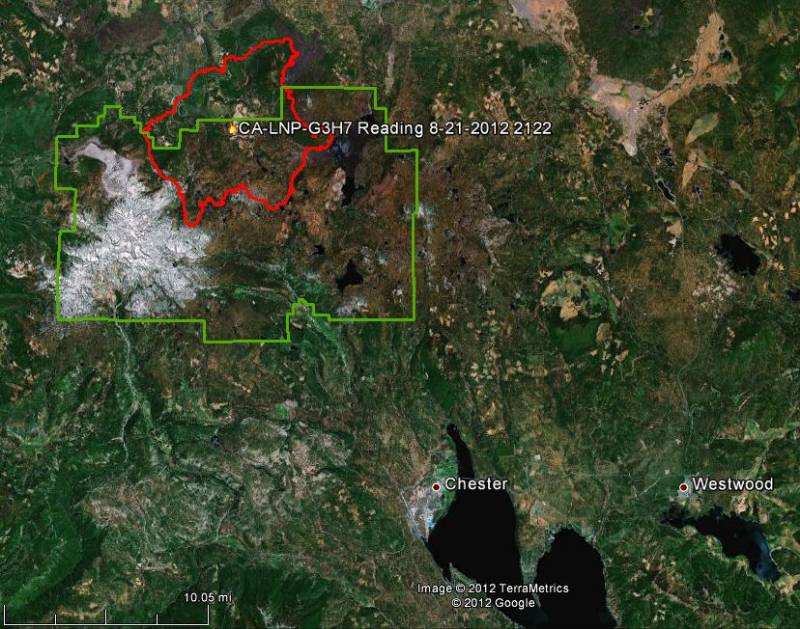

The National Park Service has released a report about last summer’s Reading Fire in Lassen Volcanic National Park in California which, after being monitored for two weeks and burning 95 acres, grew to 28,079 acres, escaping the park boundaries. The fire started from a lightning strike on July 23, 2012 and was contained on August 22. For the first two weeks it was managed under a “Wildland Fire for Resource Benefit” strategy.

The expectation was that they could stop the fire when it reached the Lassen National Park Highway, about a mile north of the point of origin. On August 6 when the fire was 140 acres the Type 4 Incident Commander transitioned to a Type 3 IC. Later in the day the fire ran for about a mile and a half, blowing right across the 2-lane highway. Then a Type 2 Incident Managment Team was ordered, which eventually transitioned to a Type 1 IMTeam on August 13. When the fire was contained it had burned 11,071 acres of US Forest Service land outside the park boundaries and 75 acres privately owned, for a total of 28,079 acres. By August 23 the National Park Service had spent $15,875,495 observing, managing, and later suppressing the fire.

As we have stated before, managing a fire with your hands tied by utilizing little to no aggressive suppression action, is extremely difficult, requiring an extraordinary amount of skill, knowledge, expertise, experience, and luck. Especially if the fire starts in mid-July, leaving 6 to 12 weeks of weather ahead that is conducive to rapid fire spread. Few people can do this. It is impossible to predict accurately how weather will affect a fire more than 10 days ahead.

Here are some some excerpts from the 53-page report:

- The Energy Release Component increased during the course of the fire to near record highs at, or above, the 90th percentile by mid-August.

- Fuel moistures in all dead fuels size classes in the park were very low during the 2012 fire season—approaching, or at, record levels.

- Beginning July 30, a six-day dry period began with minimum relative humidity decreasing slightly and predicted to be as low as nine percent. With this dry air mass, poor nighttime relative humidity recoveries also occurred. During this time period, the temperatures were predicted to be in the mid-eighties and winds southwest five to ten mph. On August 4, a weather system bringing moisture and a significant increase in thunderstorm activity was beginning to move into the area. The Sacramento National Weather Service issued a Red Flag Warning for dry thunderstorms from midday August 4 to midday August 5. This thunderstorm system did produce numerous lightning strikes in the Park, starting two confirmed fires on Sunday, August 5.

- A modeling program, Fire Spread Probability (FSPro), was first used on August 6. The program under-predicted the fire spread during the course of the fire. During the summer of 2012, this under-prediction of fire spread occurred on the majority of the fires in the mixed conifer fuel type.

- Outreach and public information directed toward local communities regarding smoke and air quality affecting public health was overlooked until August 10. Even if a fire never leaves the Park, smoke impacts to neighboring communities need to be addressed and communicated early.

- During the Reading Fire, the terms and labels “controlled burn,” “let burn,” prescribed fire,” and others appeared in newspapers, other media reports, and blogs. These multiple descriptions—dated for various fire management options—opened Lassen Volcanic National Park to criticisms from elected officials, residents, and business owners. The language and terminology used in public communications is tremendously important and must be consistent with national fire policy. To the greatest extent possible, the fire language used in communication to the public should be up-to-date, standardized, be easy-to-understand, and match national fire policy.

- A Type 3 Incident Commander: ““Terminology is inherently a problem in our agency. We don’t do ourselves any favors because the terminology is confusing and misunderstood.”

- A Type 4 Incident Commander: “Our terminology has changed so many times that people don’t trust it.”

- The Type 2 Incident {Management} Team, representing Lassen Volcanic National Park and Lassen National Forest, held the first public meeting approximately three weeks into the Reading Fire. The need for community meetings must be anticipated early. Close coordination and planning for public meetings is essential. Using a skilled facilitator is helpful.

- Park Fire Staff: “I didn’t ‘what-if’ enough. I should have painted a darker picture.”

- Try to Avoid Tunnel Vision on Success. Beware of focusing too much on confirming evidence; evidence that your plan is working. Look for reasons to suspect that your plan might not work. Have a preoccupation with failure. Try not to get tunnel vision on success. (Note from Bill: a report on an escaped prescribed fire in Yosemite National Park in 2009 cited the “hubris of success”.)

- People were using the “slideshow” of experience of past fires in the Park, which were fairly benign and low intensity. These other fires were at different times of the year and different years. The fire potential for this fire was therefore underestimated.

- Units should prepare in advance for hosting incident management teams by having in-briefing materials ready (delegations of authority, leader’s intent, mop-up and turn back standards, clarification on “Minimum Impact Suppression Techniques” (MIST), and resource protection guides, etc.). In-briefing and transition materials are extremely important. They will help teams get up-and-running quickly. Parks or units that don’t host fire management teams frequently should pre-identify locations for Incident Command Posts. Any necessary land use agreements should be prepared ahead of time.

- Firefighting resources should be ordered early, even if it seems like they may not be available, or that the fire may not rank high enough in priority.

- “Inciweb” and “Firenews” needed to be implemented earlier and updated daily to keep the public informed through maps, descriptions, increases in fire behavior and other factors. Today’s instant access to information through social media makes it imperative that accurate and timely information is provided to stakeholders early—perhaps utilizing the same technology.

- All units should have a unit-specific Resource [Adviser] Guide.

- Firefighter and public safety was clearly the Reading Fire’s primary objective. A strong commitment to minimizing exposure to risk resulted in no fatalities or serious injuries.

- Trainees were used in key positions for developmental goals with appropriate mentoring and oversight.

- An extensive information “trap line”—places where fire information is posted for the general public—was established over 187 miles with 35 stops.