The rollover of the U.S. Forest Service fire engine near Clovis, California July 12 that injured five firefighters, one seriously, is another reminder about how frequently wildland firefighters are injured in vehicle accidents.

Here are some snippets of data:

- A study by Dick Mangan of Blackbull Wildfire Services found that between 1990 and 2009 the leading causes of death of wildland firefighters were: 1. aviation accidents; 2. vehicle accidents; 3. heart attacks/medical causes; and 4. burnovers. From 1990 to 2006, 71 firefighters died in vehicle accidents.

- The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center reported that driving-related incidents was the leading category of incidents that were reported to the Center in 2014.

- This is a very unscientific data set, but since we started Wildfire Today in January, 2008, we have reported 17 rollovers of fire vehicles that resulted in 44 injuries to firefighters working on or responding to a wildland fire. That does not include non-rollover vehicle accidents, rollovers of heavy equipment (of which there were quite a few), or accidents that occurred in Australia and Canada. Articles on Wildfire Today, 28 of them, tagged “rollover”.

What can be done to reduce the number of these injuries and fatalities?

Training

The first thing that is always discussed in accident prevention is training. The most difficult factors to deal with in driving a fire engine are the weight, the center of balance (top-heavy), the physical stress of driving long distances or after a 14-hour shift, and the mental stress of driving an emergency vehicle. All of these are difficult, but not impossible, to train for. Some fire agencies have Engine Academies that actually put trainee drivers behind the wheel, which of course can be extremely beneficial. But it is not easy to train a driver how to react in a split second when they are faced with the sudden decision about possibly hitting the brakes, changing direction, neither of the two, or a combination of the two. Operating a top-heavy 12,000 or 26,000-pound vehicle limits your options. A quick flick of the steering wheel can initiate a rollover.

Driver’s qualifications

When I worked for the National Park Service (NPS) the agency had virtually no specific policy or qualification requirements for the drivers of smaller fire engines, such as a Type 6, other than having a standard state driver’s license. Or if they existed, they were not enforced. A person who had been hired off the street having never driven anything larger than an Austin Mini could be placed behind the wheel of a 15,000-pound top-heavy fire engine.

We checked with the NPS today, and spokesperson Christina Boehle told us that their requirements for driving fire vehicles are on pages 6-9 of Chapter 7 in Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation (Red Book). This publication includes policies for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and the National Park Service (NPS) and supplements other manuals the agencies have. The Bureau of Indian Affairs does not participate in the Red Book program.

In addition to holding a state driver’s license, all drivers covered by the Red Book have to take a defensive driving course. And, as required by Department of Transportation regulations, all drivers must obtain a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) for operating vehicles weighing 26,001 pounds or more.

Other than defensive driving, no specific additional training is required by the Red Book for driving fire equipment, except for the BLM and USFS which require “driver training”. Those two agencies also complete paperwork to document driver qualifications.

The Engine Operator position has been removed from the Wildland Fire Qualification System Guide (310-1), but now it can be found in the Federal Wildland Fire Qualifications Supplement. The training requirements listed in the document for the position vary widely among the five federal land management agencies. The BIA does not even recognize the position, and on the other extreme is the BLM which requires seven training courses, only five of which are directly related to operating an engine. The FWS and the BLM require the Engine Academy or a BLM Engine Operator Course, respectively. There is also a Position Task Book for Engine Operator.

Seat belts

It almost seems too obvious to mention, but wearing seat belts is the one thing that every person in a vehicle can do to reduce injuries or save lives in a vehicle accident. Most federal land management agencies have policies requiring the use of seat belts.

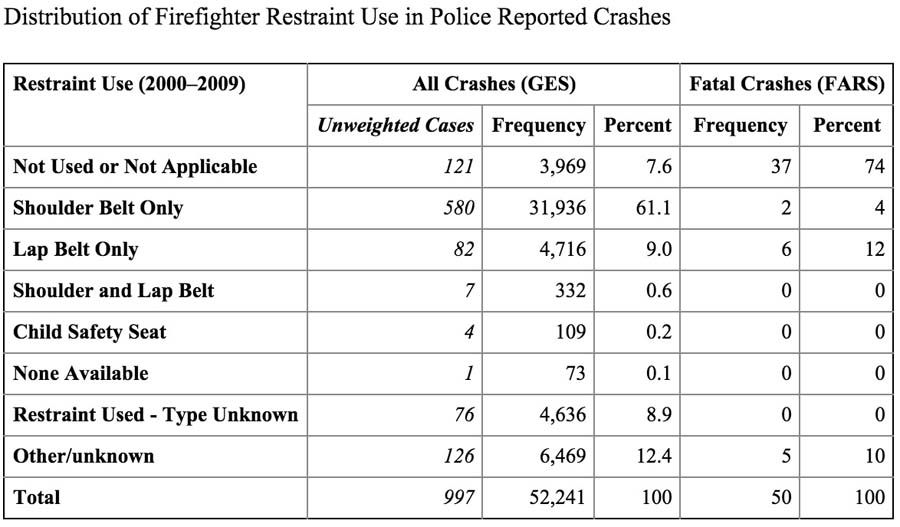

A study by the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine found that in 7.6 percent of fire truck crashes that were reported to the police some of the occupants were not wearing seat belts, and 74 percent of the fatal crashes involved the non-use of seat belts.

Supervisors at all levels need to proactively ensure that firefighters in all types of vehicles, including crew carriers, wear seat belts.

Engineering

You may have seen Austin Dillon’s horrific-looking crash in the July 5, 2015 NASCAR race. His car became airborne at about 180 mph and crashed into the fence, coming to an immediate stop. Then when it appeared to be over and the remains of the car were upside down, an out of control car hit it with force, causing it to spin around several times on its roof.

The car was barely recognizable as a car after the crash. The front one-third and the rear one-third were gone, but the integrity of the driver’s compartment and his seat remained intact. The only object in the interior that came loose was the radio. Mr. Dillon walked away with only a few bruises.

This shows what can be done to prevent injuries in a very serious vehicle crash. It is not practical to harden the cab of a fire engine to the degree seen in NASCAR, but there are steps that can be taken to prevent the roof from collapsing in a rollover, such as was seen when U.S. Forest Service Engine 392 rolled over in Wyoming in 2013 (see photo above).

The wildland fire agencies should fund research conducted by engineers to determine how to prevent the passenger compartments in their fire engines from collapsing in accidents.

Ensure that fire vehicles are not overweight

In the 1990s one federal land management agency was accepting new Type 6 engines from manufacturers that exceeded the Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW) the day they were delivered after being filled with water.

Adding thousands of extra pounds beyond the GVW to an already top-heavy vehicle can make it difficult to control, especially when making an evasive maneuver or a quick stop. The additional weight is also hard on suspension systems and can cause premature failure of various components.

While federal land management agencies have been guilty of overweight fire trucks, some local fire departments have had the same problem. Too many departments take a Ford F-150 or F-250 and add a very heavy tank and pump package, exceeding the manufacturer’s designed GVW.

A study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health documented some extreme cases, including one where a military surplus tanker designed to carry gasoline was transporting 1,200 gallons of water primarily off road, which put the weight of the loaded vehicle approximately 7,000 pounds over the cross-country weight rating.

More information:

—Analysis of Firetruck Crashes and Associated Firefighter Injuries in the United States

—Three keys to preventing fire a apparatus rollovers

—Preventing Death and Injuries of Fire Fighters Operating Modified Excess/Surplus Vehicles

Driving these vehicles is a different world. For the military I had to take a two week class including driving on/off road 4X4 and 6X6 with loads under the eye of a experienced instructor. Then several months with a experienced driver.

I feel a mandatory heavy duty vehicle driving class should be required along with lots of road time plus a CDL. Working on narrow, winding unimproved mountain roads adds hazard with a sometimes top heavy vehicle.

In our jurisdiction, volunteer fire fighters must pass an annual emergency vehicle operator classroom class and test, and apprentice with experienced drivers before being allowed to obtain an emergency vehicle operator endorsement on their driver’s license, which is required for operating any department vehicle.

Is there any possible technology or training that could give operators warning that a vehicle is approaching roll instability? I don’t know of any safe way to actually determine a big, top-heavy vehicle’s roll stability limits in a way that would be useful to an operator.

And those front right tires will sneak off and get into all sorts of mischief if you don’t keep em on a tight leash…. lack of experience, poor visibility, fatigue, and soft, narrow, slippery roads can turn a good day really bad really immediately.

Not to mention all the problems are further compounded when the “add 15 MPH” lights are activated on the roof.

We dont have a very good program at my VFD. But we dont allow rookies or persons with little experience driving trucks to drive the tender or heavy rescue.

Good discussion.

There is an Engine Operator position described in the FEDERAL WILDLAND FIRE QUALIFICATIONS SUPPLEMENT – January 2015 and a Position Task Book in the Agency Specific taskbook section on the nwcg website:

http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/docs/supplement-2015.pdf

http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/taskbook-agency/blm-fs-fws/enop.pdf

Thanks Chris. I was aware of the PTB, but not the actual Engine Operator position in the Supplement. I added it to the article.

1995 Engine Operators Academy Stead AB, Nevada

Type 1 thru 6 training to include Roadeo. Not that it prevented accidents…but rollovers were heavily discussed.

Certainly the LMA should have thought more of this through in the last 20 years as far as more in depth training.

Apparently. ….it is another in the history of non standardized training in ground operations that maybe NHSTA and DOT need to put a little pressure on LMA’s like NTSB puts on aviation