(Originally published at 9:07 a.m. MDT July 10, 2018)

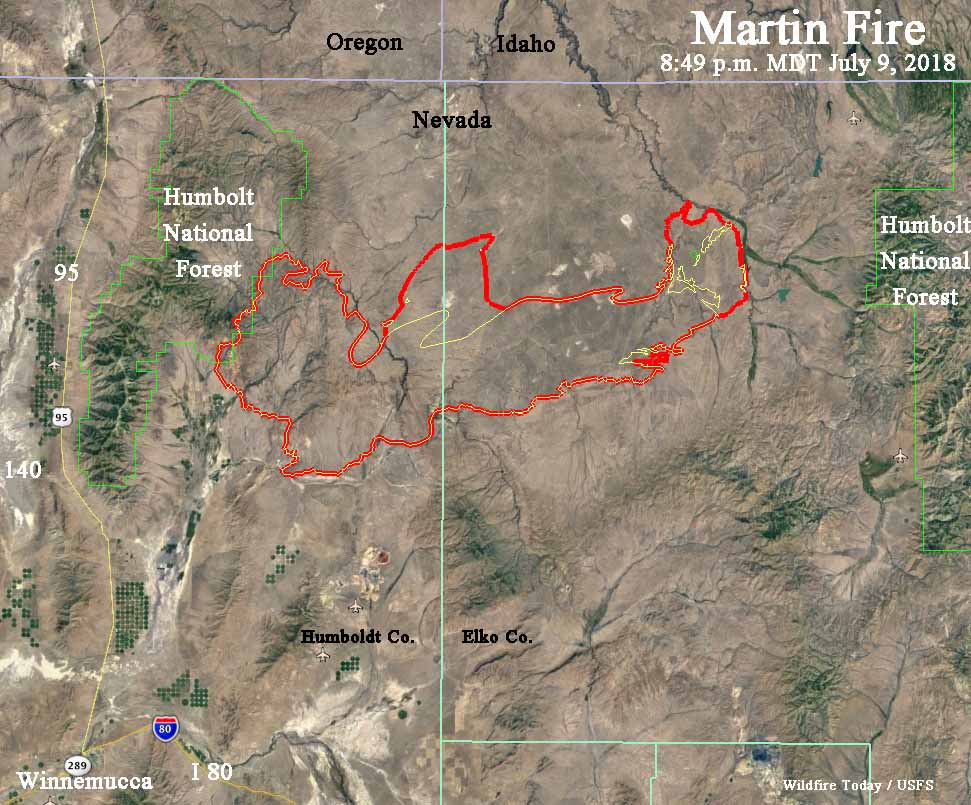

When a wildfire reaches 100,000 acres we often refer to it as a “megafire”. But what name do we put on a fire when it is four times the megafire threshold? The incident management team on the Martin Fire in Northern Nevada estimates their fire has burned approximately 425,000 acres. (I think we should reserve “gigafire” for a 1 million-acre fire.)

According to the National Situation Report there are only 634 personnel assigned. That is extremely low density of firefighters for such a huge fire — it stretches for 56 miles, west to east. Let’s assume for a moment that the perimeter is 150 miles (it is probably more). If so, that is about three people per mile of fireline, not including support personnel. However with mostly light fuels, there is less mop up after the spread is stopped, requiring fewer personnel.

With the long distances, limited numbers of firefighters, and what may be difficult access, firefighters on the Martin Fire say they have developed an innovative approach to containing the blaze.

Firefighters know that air tankers and helicopters dropping water or retardant do not put out fires. Under ideal conditions they can slow them down enough to allow ground-based firefighters the opportunity to move in and actually put out the fire in that area. If there is no ground support working with the aircraft, the chances of success are very low. Reading between the lines of an update about the fire (embedded farther down) it appears that firefighters realized that in some instances the fire was spreading beyond retardant drops. It is not clear if the fire burned through the retardant, spotted over, or burned around the retardant.

The tactic they decided to deploy involved using a combination of water-scooping air tankers, retardant-dropping air tankers, and firefighters building line on the ground. Aircraft that drop water, helicopters or fixed wing, apply it directly to the flaming front, since dropping it out ahead of the fire is often not effective since it does not adhere to the vegetation or have a long-term effect like retardant.

Here is how they described what they did:

Crews and equipment are making excellent progress building containment lines along the southeast flank of the fire. Due to the heavy, fine fuel loads, high winds and extremely fast fire rates of spread, an innovative tactic has been developed to combat these conditions using a three-prong attack. First, a long line of water is laid down by super scoopers, immediately followed by a retardant drop from air tankers. The approaching fire is thus cooled sufficiently that dozers and crews can safely and immediately dig a containment line right up against the side of the retardant line facing away from the flame front. Very close timing and coordination of air drops of water and retardant with ground forces has been proven to be the most effective tactic in these volatile burning conditions.

The part that may be innovative is slowing the flaming front with scooping air tankers AND then putting retardant just outside the edge of the fire. And as usual, quick followup by ground forces is essential.

Here are links to videos shot on the Martin Fire of drops by a DC-10 and two water scoopers.

Is it interesting that these firefighters, like many others in Canada and Europe, know that water-scooping air tankers are a very important tool in the toolbox. However, this year the U.S. Forest Service decided not to have any of them on exclusive use contract. The ones being used thankfully were available on a Call When Needed contract. And the number of retardant-dropping large air tankers on EU contracts were cut by one-third over last year.

They are also having success on the Martin Fire using a local task force:

Yesterday, fire spread slowed significantly due to the hard work of the local Elko Task Force that hit the head of the fire early Sunday morning and throughout the day. The task force took advantage of the fire naturally slowing as it entered flatter terrain with lesser fuel loads. Operations personnel report that the fire is moving into patches of greener vegetation such as Siberian wheat grass, which was planted as part of the BLM’s rehabilitation and fuel treatment efforts on previous fires. Green fuels slow the fire’s advance, making it easier for bulldozers and engines, with the aggressive assistance of super scooper air tankers and heavy and light helicopters, to catch up and get containment lines in place.

The head of the fire on the east side has approached and so far has not crossed the major drainage in the 3-D map below, thanks, no doubt, to the points brought out in the preceding quote.

The Martin Fire is bringing in Beth Lund’s Type 1 Great Basin Management Team to handle the east side, while Taiga Rohrer’s Type 2 Great Basin Incident Management Team will continue to take care of the west side.

First, thanks for your article. I just want to add the following antecedent. The paragraph that indicates “… instances the fire was spreading beyond retardant drops. It is not clear if the fire burned through the retardant, spotted over, or burned around the retardant.” It caught my attention; however I remembered that I saw an image of #MartinFire drops where we can see the lack of continuity and overlap of the retardant drops. See: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/photograph/5899/15/79671

We know that to stop (not extinguish) the advance of fire the construction of chemical (or mechanical) lines must be continuous, overlapping and with the adequate coverage level to fuel (vegetation), which unfortunately did not occur at least in the area that It is appreciated in the picture. The reasons may be quite understandable but it is certainly a cause of the lines being overstep by fire.

Northern Nevada is a tough place to fight fire. It looks pretty flat but the mountains are incredibly steep and rugged. Fuels are extremely flashy with generally high rates of spread. Logistics are very complex and difficult due to the remoteness. There are generally no trees or green grass patches to camp in or under and you end up sleeping in the puff dust. What would make more sense would be to invest money in the restoration of native plant communities which would mean more native bunch grasses, which stay green longer and don’t burn with so much vigor like cheat grass. There are no easy answers.

Glad to see this innovation tested in the field. This tactic was proposed to USFS in Boise over a year ago and response was “that is not how it is done”.

It is worth noting that the 747 SuperTanker has two separate tank systems, one could be filled with water (perhaps with a fire suppressant), the other with retardant. With two passes (one sortie) this would quickly allow a 9600 gal. water/suppressant drop to weaken the fire and a 9600 gal retardant drop to slow/barricade it. Also, the retardant pattern from the 747 is wider than other drop patterns (although using half the system this way would result in a CL4 retardant drop), potentially giving better chance of preventing a jump of the retardant line. The only way to determine if this is a useful approach is to try it. Experimentation/innovation in the field is the way to create new and effective techniques. A salute to those who have sought to develop new techniques.

A sincere thank you to all the courageous and hard working fire crews and aircraft personnel! You are never given enough credit by the public and all those who directly and indirectly benefit from your dangerous and heroic efforts.

“…firing out from roads ahead of the fire…”

Anyone remember the 1999 Sadler Fire? Carlin NV?

Looks like they are finally using good tactics to control the fire, they should also be firing out from roads ahead of the fire. This looks to be mostly in cheat grass on fairly flat ground. Using tractors building line well ahead of the fire and firing from these lines in conjunction with existing roads could

stop this fire.

Bob Service 30 year veteran fireman

Fireman@reagan.com