Today Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke tweeted that trees killed by beetles “are an added risk for fire”. This is misleading at best, and incorrect when all of the facts are brought to light.

This is not a healthy forest. This is what @realDonaldTrump, @SecretarySonny and I refer to when we talk about removing dead and dying timber. These gray trees were killed by a beetle infestation and now are an added risk for fire. (Helena NF in MT) pic.twitter.com/lGvXx4XZfi

— Secretary Ryan Zinke (@SecretaryZinke) November 21, 2018

And as before when the Secretary and the President said “poor forest management” and “environmental radicals” are responsible for the recent major fires in California, the issue can’t be described or solutions offered using just a few words. It is nuanced and complicated, not lending itself to a 280-character conversation.

In 2010 I first became aware of research by scientists that found fire severity decreases following an attack by mountain pine beetles. Since then additional studies have led to a more thorough understanding of the process.

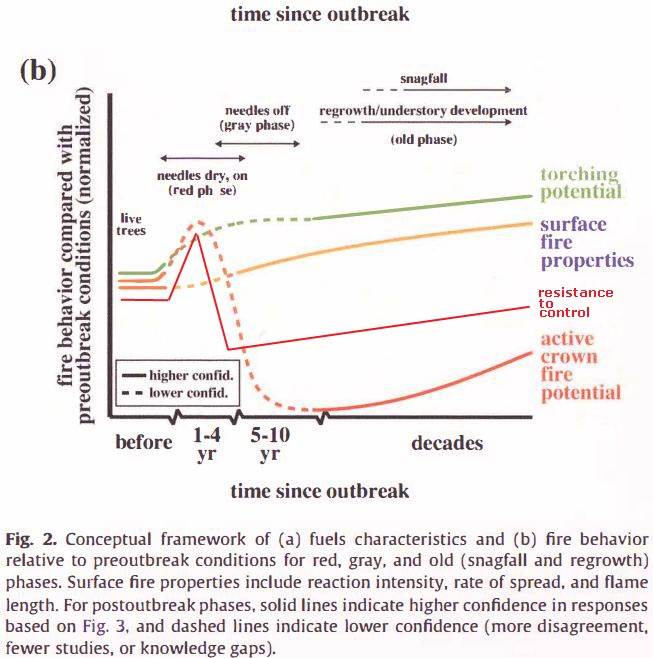

Three factors or characteristics of a beetle-killed forest affect the behavior of a wildland fire.

- After a tree is killed by a mountain pine beetle, the needles turn brown or red; this is known as the “red stage”. The dead red needles remain on the tree for one or two years and then fall off. During this period the potential for a crown fire that moves above the ground through the tops or crowns of the trees can increase. After the needles drop the potential for a crown fire is close to zero. A crown fire can’t be controlled. No amount of fire retardant dropped by aircraft, water applied from the ground, or dozers building fire lines will stop it. This is the largest factor to consider when discussing fire behavior before and after a beetle outbreak. After a couple of years, it is easier to control a fire in a beetle-affected forest than one that is green, and this effect lasts for decades. There are other factors to consider also.

- After 5 to 15 years the limbs begin to break off a beetle-killed tree and then the top can break off and eventually the remainder of the tree falls to the ground. This adds fuel to the forest floor and can increase the intensity of a fire that burns along the ground. It is easier to control a surface fire, even one burning intensely, than a crown fire .

- After a decade or two the potential for individual or multiple tree torching can increase. This involves the burning of an entire standing single tree or multiple trees. These latter two issues, surface fire intensity and torching, add to the challenges for firefighters, but the reduced crown fire potential greatly outweighs the other two.

This can be distilled into what I have called Resistance to Control (RTC) which considers those three characteristics of a beetle-killed forest. One to two years after the insect-attacked tree dies, the RTC increases, but after that it decreases immediately and remains lower than before the attack for several decades. Eventually live trees replace the dead ones and all three characteristics return to their normal state.

The chart below summarizes these three issues. It is from a paper titled Effects of bark beetle-caused tree mortality on wildfire, written by Jeffrey A. Hicke, Morris C. Johnson, Jane L. Hayes, and Haiganoush K. Preisler. With apologies to the authors of this very good research paper, I took the liberty of adding a Resistance To Control variable (the red line) to their chart.

There is still another characteristic of a beetle-killed forest that is important to consider. Pine beetle outbreaks do not automatically lead to catastrophic wildfires. In 2015 University of Colorado Boulder researcher Sarah Hart determined Western U.S. forests killed by the mountain pine beetle epidemic are no more at risk to burn than healthy Western forests. Other scientists have found similar results.

Mr. Zinke referred to a forest with evidence of tree mortality caused by insects as a forest that is not healthy. Insects are part of the ecosystem; they will always be part of the forests. We will never be able to eradicate them, nor should we. The populations of the insects run in cycles. They feed on trees to survive.

In addition, the “dead and dying timber” as a result of fires or insects that Mr. Zinke wants to remove is an integral part of the forest ecosystem. The National Wildlife Federation says, “Dead trees provide vital habitat for more than 1,000 species of wildlife nationwide. They also count as cover and places for wildlife to raise young.”

An article at The Hill November 20 covers how Mr. Zinke and Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue are hoping that the new version of the Farm Bill will allow more logging that among other objectives, “beautifies the forests”, as Mr. Zinke is quoted as saying.

Roy Renkin, a Yellowstone National Park Vegetation Management Specialist, wrote in 2010, “Disturbances like insect outbreaks and fire are recognized to be integral to the health of the forests,” he said, “and it has taken ecologists most of this century to realize as much. Yet when these disturbances occur, our emotional psyche leads us to say the forests are ‘unhealthy.’ Bugs and fires are neither good nor bad, they just are.”

(Here is a link to all articles on Wildfire Today about beetles and fire.)

Literally the most academic and polite conversation I have witnessed.

Don’t get too spun up about what Zinke says concerning forests. However, lend an ear when Sonny Purdue pipes in.

Part of the problem is that loss of natural fire due to human actions led to the problems with the extensive beetle kill and now climate change producing a loss of moisture reduces the health of forests. It’s a very complex issue. I do not trust career politicians or appointees with limited or no background in these matters. We should allow nature to take its course and not apply human values such as beauty to natural selection.

Allowing nature to take it’s course does not seem tenable in my opinion….all across the west, neighborhoods are springing up in the middle of what used to be nowhere….

Spend a small amount of time researching the population growth of our country…..”nature’s course” did not include this newly populated landscape..

Several posts have talked about the heavy fuel loading and higher temps in these bug infested stands..that is spot on..

Once 30% to 40% of the stand is dead and down, you can expect radiant heat that makes direct attack impossible..What is also concerning is these higher temps effectively cook the soil and can often nuke an area for decades..

Part of the answer should be a huge increase in fall time burning to eliminate some of the build up..and this should include wilderness area, that are presently off limits from anything of the sort..

Can’t see that happening…would probably take an act of congess (literally)

If you look at the maps produced by our host of the King fire, you will note the fire burned right on past numerous logged areas. Either the fire burned in brush fields not removed by logging activities or the fire spotted past areas of low fuel density. Forest management to reduce fire hazards is going to have to take into account the ongoing drought and increase in severe weather predicted by climatologists. Do we allow/require much larger logging shows and do we require landowners to mow the brush every year? What will be probably millions of acres of brush mowing?

Here is a link to the archives for the 2014 King Fire between Placerville and Lake Tahoe, California.

Jim: In California and the Pacific Northwest catastrophic wildfires (100,000+ acres burned and/or loss of human life) almost invariably travel on an east wind for often stated and well known reasons. In recent decades they almost invariably start and/or take place on federal lands that do not allow extensive logging, grazing, or prescribed fires. In Wilderness areas — in which these fires have become common — mowing with machinery isn’t allowed, either. A perfect situation for massive wildfires to develop and take place — as was accurately and reasonably predicted more than 25 years ago. Treating flash fuels on an annual or biannual basis is only important in strategic locations such as the eastern and northeastern boundaries of communities or other areas needing such protection. In those locations “brush mowing” can also be achieved with grazing, broadcast burning, and/or herbicides. Most “landowners” needing to achieve these results are the federal government.

Much of this has already been formally published and discussed in the past. RTC definitely does not go back below pre-outbreak levels for several decades, see https://www.firescience.gov/projects/09-S-03-1/project/09-S-03-1_Page_Alexander_and_Jenkins_2013.pdf

Every situation is unique, any broad generalization in either direction will almost certainly be wrong for a substantial number of specific cases.

The 2016 Beaver Creek fire north of Walden, Colorado burned in areas of beetle kill. Wildfire Today reported on this fire and had numerous reports on how difficult it was to control. Extreme amounts of radiant heat were produced by the fuels. I encourage anyone who thinks fires with heavy loads of beetle killed timber aren’t a problem should review the Wildfire Today articles on the Beaver Creek wildfire. It seems to me authors Hicke, Johnson, Hayes, and Preisler should review information that’s available on the Beaver Creek wildfire.

I disagree with the oversimplified graphic. Bug kill isn’t an all or nothing proposition, so when those bug killed trees go down they add tons of fuel per acre that allow those fires to climb into the crowns and burn hot.

When the needles fall off the bug trees and the trees go down it is in effect thinning the forest. It does not “add tons of fuel per acre”, it redistributes it to the ground. In your scenario, at that point are there enough aerial fuels left to support a crown fire? The answer is, generally no.

You make a good point – the fuel has always been there. And I can only speak to my own experiences on the Fort Rock Ranger District of the Deschutes NF. I’ve rolled up on sustained crown fires with so much dead and down we couldn’t begin to knock the fire down. Fuel 3 and 4 feet deep, you could hardly climb through it. Yes, plenty of Lodgepole still standing to carry the fire. Most operations became a dozer show almost from the get go. My opinion is that bug infestation leads to fires that are (vastly) harder to suppress – which would make them an added risk.

Being dead and down affects availability. While green, it’s obvious the boles and branches won’t consume. Dead, dry, and redistributed to the ground does equal more fuel. More fuel, high heat output. Residual stand, bye-bye. As far as suppression goes, my experience is that heavy dead and down makes the job much tougher. Whether or not to suppress these fires well away from habitation is a different subject. “Only you can postpone wild fires”, said with Smokey Bear voice.

Interesting that the B&B complex came up..in 2003 I worked over the B&B in a variety of aerial supervision roles…ASM,ATGS and HLCO over a 6 week period.

And in 2017, I got to fly over it daily to work the Whitewater and many other fires.

In 03, on the B&B, we had good success on the eastern boundaries where fuel treatment had been performed in previous years..ground crews know that they can catch fire in these treated areas, or use them to light fire from..

That is not the case where you have closed canopy, overgrown stands…Often, these overgrown stands have a high amount of decadence and dead& down, with, or without a beetle kill component.

And the B&B had plenty of that in spades.

I think all of us who have been around this business for any amount of time realize that crown fires are not controllable….the fire is going to run it’s course, and we will pick it up where we can..

Fortunately, we don’t see sustained crown runs that frequently.

(Comparing the two) trying to control a “crown fire” and a fire established in a 2nd or 3rd stage bettle killed block is like comparing apples and oranges..each has it’s difficulties.

I am very familiar with fighting fire in beetle killed (white)spuce in alaska, both on the ground and from an aerial supervision perspective.

The beetle killed areas are much harder to control fire in…for a # of reasons

1) the jackstrawed dead and down make any ground movement difficult or impossible.

2) the jackstrawed material shades a lot of the fuel from receiving retardant, or even water directed from a hose.

3) the beetle killed forest transitions from having previously damper forest floor, absent of grass, to a grass infested nightmare of dead and down. But, the beetles don’t take everything, they leave enough smaller trees to create a real problem of torching….

And once the canopy is gone, both wind and sun play a critical role in pre-fire and post-fire conditions on the ground.

Having fought plenty of fires pre-beetle kill, and since the early 90’s fought plenty more in beetle kill,both red stage and grey stage , I have to disagree with your overall conclusions Bill..

It may be the case that in some of the drier forestlands of the western states, you don’t get the same aftermath of ground fuels mixed in with the dead and down, and if that is the case, then you really need to draw your concusions based on a wider set of facts, that takes location and post beetle flora into account.

Alaska uses the cffdrs( canadian forest fire danger rating system) , and I would offer that the cffdrs model templates consistantly show much higher ERC’S and resistance to control in bettle damaged stands. Or at least the ones we have used to try and get a handle on our extensive white spruce damaged stands in Alaska.

Regards,

Vean Noble

The occurrence of millions of dead trees in the past few years due to drought has two very important concerns other than an effect on fire behavior. The first is an unprecedented safety risk to the public in general, who live in such areas, and specifically to firefighters working in these areas. Parts of trees will be breaking off for the next few decades, greatly complicating where and how to perform an initial and extended wildfire response. The second is the massive amount of heating to which soils will be exposed when great amounts of downed material burn, increasing erosion potential and retarding postfire succession. Prescribed fire can play an important part in the reduction of this material gradually, under less than tinder-dry conditions.

As a former carpenter and wildland firefighter who became a fire scientist, my hunch is that when beetle-killed forests do burn at the grey stage, it is probably the brush, dead/down, or small regen that is carrying the fire. None of these carriers would be removed by logging. Some use of the standing dead is good, but it should be subject to public comment (for and against) to optimize the outcomes on public lands.

Thank you for this ‘real information.’ It is a complicated issue that deserves thoughtful evaluation and communication, missing from those responsible for our federal lands. Not so great.

That is not the whole story.

1. This group of top California fire ecologists is very worried about the fire potential of the 2014-2016 beetle mortality. Stephens, Scott L., Brandon M. Collins, Christopher J. Fettig, Mark A. Finney, Chad M. Hoffman, Eric E. Knapp, Malcolm P. North, Hugh Safford, and Rebecca B. Wayman. “Drought, tree mortality, and wildfire in forests adapted to frequent fire.” BioScience 68, no. 2 (2018): 77-88.

2. Most British Columbia fire ecologists, based on experience there in this century, believe beetle kill makes fires worse and more probable. Perrakis, Daniel DB, et al. “MODELING WILDFIRE SPREAD IN MOUNTAIN PINE BEETLE-AFFECTED FOREST STANDS, BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA.” Fire ecology 10.2 (2014).

3. Your generalization about crown fires uncontrollable and other fires controllable is exaggerated. Look at the uncontrollable Camp fire (mainly in brush, fallen dead tree debris, 9-year-old plantations, grass.)

4. Look at your chart from Hicke et al. It shows increased torching potential. What happens where the overstory trees were, say 60 or 70 % of the canopy at the time of beetle epidemic and have subsequently experienced 15 years of release? And the wind is blowing? I think torching turns into crown fire. The chart was presented as a “conceptual model,” not a graph of any particular set of study results. Hicke’s conclusions include this: “the impact of beetle killed trees can become significant when compared with unattacked stands.”

Daniel-

1. We wrote about that study January 17, 2018. Our article has the abstract and the conclusions.

2. That study is referenced in the above study. It concluded that rates of spread are increased during the one to two year red phase, something that almost everyone agrees with. As far as your statement that “Most British Columbia fire ecologists….”; that is not at all what the document said. Information about enhanced ROS after the red phase, according to the paper, is anecdotal and not supported by data in the paper. Here is a quote: “The British Columbia experience during the past decade has been one of heightened fire behaviour during epidemic MPB conditions in pine stands.” There are a number of studies, with data, that concluded otherwise, at least in the United States.

3. As you said, it was a generalization, which does not include outliers. On the first morning of the Camp Fire “wind speeds as high as 72 miles per hour were recorded.”

4. Both of the papers referenced above have similar conceptual diagrams about the long term fire behavior following a beetle outbreak. They agree that after a few decades the potential for crown fire slowly increases, but within the limited range of the projections the crown fire potential does not rise to what it was before the outbreak.

Yes good article. There is an extensive body of science on this. Sad that there is so much misinformation about dead trees out there.

Bill:

In general, most of what you say is true — but, in general, what the President and Zinke are saying is also true. In the early 1990s there was a beetle outbreak on the Santiam Pass in western Oregon Cascades. I was quoted in a national publication in 1994 saying the area was in greater risk of wildfire. Maps and photos were used to survey the damage and made front page news in Salem around the same time. In 2002 the B&B Complex Fire covered 90,000 acres and was an almost exact footprint of the 10+ year-old beetle kill. As predicted and forewarned.

I think you are exactly right when it comes to fighting these fires — no stopping a crown fire — but that Trump and Zinke are correct when it comes to increased wildfire risk. The fact is that dead conifer trees are little more than dry, pitchy firewood when they are dead, whether by bugs, disease, or wildfire (which removes the needles immediately). The 6-Year Jinx of Tillamook Fires — resulting in part with earlier fires related to 1890s bug-kill — of 1933, 1039, 1945, and 1951, and the “17-year Jinx” of catastrophic wildfires emanating from the Kalmiopsis Wilderness in 1987, 2002, and 2017 were joined by the 2018 Klondike Fire this year.

Dead tree burn hot, and the risk of wildfire increases with mortality has been my observation and also my research findings.