Scientific American has produced a video that describes the formation of the fire tornado that burned and scoured a mile-long path as the Carr Fire burned into Redding, California July 26, 2018.

In the video below, click on the little square at bottom-right to see it in full screen.

There were two fatalities on the Carr Fire that day. Redding Fire Department Inspector Jeremy Stoke was burned over in his truck on Buenaventura Boulevard. On the other side of the Sacramento River, on the west side, Don Ray Smith was entrapped and killed in his dozer.

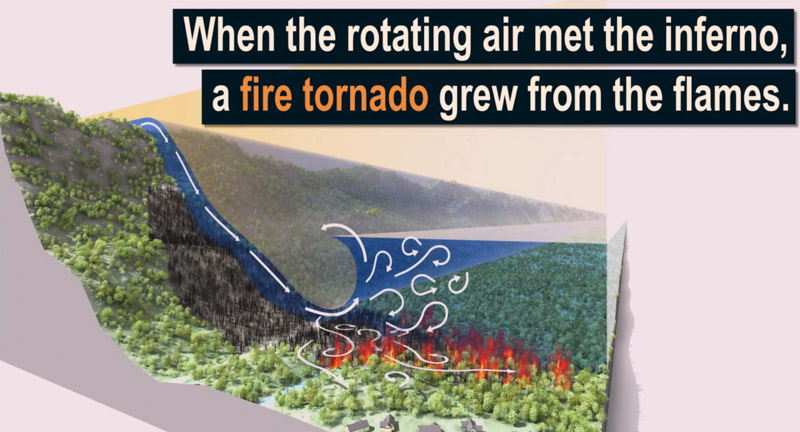

According to a Green Sheet report by CAL FIRE, the conditions that resulted in the entrapment of three dozers and the Redding Fire Department Fire Inspector that day were due to the fire tornado — a large rotating fire plume that was roughly 1,000 feet in diameter. The winds at the base were 136-165 mph (EF-3 tornado strength), as indicated by wind damage to large oak trees, scouring of the ground surface, damage to roofs of houses, and lofting of large steel power line support towers, vehicles, and a steel marine shipping container. Multiple fire vehicles had their windows blown out and their bodies damaged by flying debris.

The strong winds caused the fire to burn all live vegetation less than 1 inch in diameter. Peak temperatures likely exceeded 2,700 °F.

The Carr Fire burned 229,651 acres, destroyed 1,077 homes, and killed 3 firefighters and 5 civilians

The news media sometimes calls any little fire whirl a “fire tornado”, or even a “firenado”. These and related terms (except for “firenado”) were, if not founded, at least documented and defined in 1978 by a researcher for the National Weather Service in Missoula, David W. Goens. He grouped fire whirls into four classes:

- Fire Devils. They are a natural part of fire turbulence with little influence on fire behavior or spread. They are usually on the order of 3 to 33 feet in diameter and have rotational velocities less than 22 MPH.

- Fire Whirls. A meld of the fire, topograph, and meteorological factors. These play a significant role in fire spread and hazard to control personnel. The average size of this class is usually 33 to 100 feet, with rotational velocities of 22 to 67 MPH.

- Fire Tornadoes. These systems begin to dominate the large scale fire dynamics. They lead to extreme hazard and control problems. In size, they average 100 to 1,000 feet in diameter and have rotational velocities up to 90 MPH.

- Fire Storm. Fire behavior is extremely violent. Diameters have been observed to be from 1,000 to 10,000 feet and winds estimated in excess of 110 MPH. This is a rare phenomenon and hopefully one that is so unlikely in the forest environment that it can be disregarded.”

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Rick. Typos or errors, report them HERE.

Evening Bill,

A few years ago you referenced research on fire tornadoes by Rick McRae* that described specific criteria for those events. In that research, the term tornado referred to an event that extended from the ground to a cloud formation above. It described how Flammagenitus/PyroCb clouds above wildfires can produce actual tornadoes.

This article, and the green sheet, capture some of the factors that would be required to produce a fire tornado (high energy release, vorticity, etc.) but don’t discuss other requirements.

This does not diminish the event as a tragedy, nor does it imply the event was any less destructive. Yet, after reading the material, I remain uncertain that this was actually a tornado.

Anyway, thanks for the article Bill. I always enjoy the fireweather stuff.

*https://wildfiretoday.com/2012/11/24/documented-fire-tornado/

Edwards,

In my opinion, there is not a scientific consensus at this point as to what constitutes a fire tornado or differentiates it from a fire whirl. As Bill mentioned, one definition was given by Goens in 1978 which is simply based on size (whirl diameter) and wind speed somewhere in the whirl. Others, notably McRae and Sharples, have argued that a true fire whirl must be “anchored to a thundercloud above”. I think what they are trying to get at there might be the idea that additional vortex stretching could come from latent heat transfer effects (causing buoyancy) up in the thunderstorm… which would mean such a vortex should be differentiated from a “normal” fire whirl which only gets its stretching from fire generated buoyancy near the ground. Unfortunately, I am not aware of any scientific investigations of the influence the thunderstorm might have on: 1) generating a fire whirl/tornado, or 2) contributing additional energy/stretching to an already existing whirl/tornado. At this point it is not clear if a thunderstorm has any impact.

A last comment. McRae and Sharples claim that the Australian fire tornado they investigated was a true tornado because the debris path showed it “skipped” in some areas… meaning it lifted off the ground (which it can supposedly do because it is “attached” to the thunderstorm above and not “attached” to the ground). It seems that current tornado research may disagree with this idea, a short discussion is given here:

https://www.spc.ncep.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/#skipping1

My personal opinion on all this is that I like the idea of using size and strength to define a fire whirl or tornado. My reason for this partly comes from my firefighter background. For one, it is simpler for a firefighter to identify while observing it. Also, I think firefighters warning other firefighters on the radio should have clear terminology to use, and that is related to safety. And so a firefighter broadcasting out that a fire tornado has formed implies a different level of danger than a fire whirl. Just my two cents… someday maybe new research will change our understanding.

There is an error in my post above. I should have said:

Others, notably McRae and Sharples, have argued that a true fire tornado must be “anchored to a thundercloud above”.