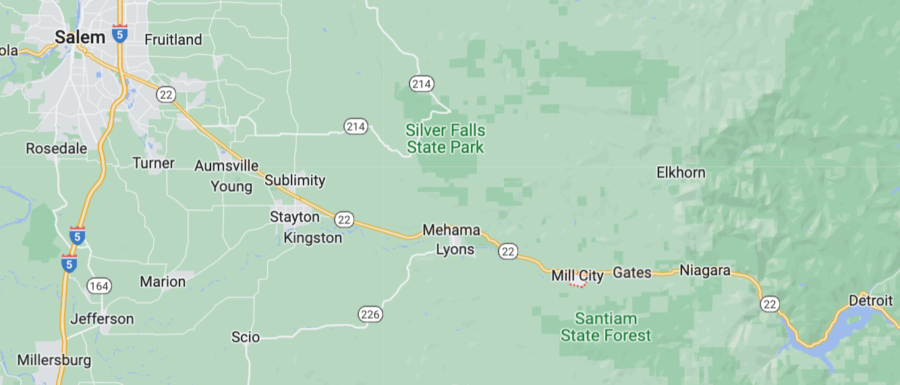

Over the Labor Day holiday in 2020, with east winds picking up toward the end of a long, hot and dry summer, Leland Ohrt was dispatched to a home not far from his own, where a tree branch had fallen on a powerline and started a small brush fire. Ohrt was Mill City Fire Chief, a VFD chief in a small town in western Oregon’s Cascades; he hosed down the fire, then drove over to Schroeder Road, where another tree branch had fallen over another powerline and was still arcing sparks into the dry fuels below. Ohrt couldn’t stop the sparking, so he hosed the utility lines with water until they exploded and de-energized themselves.

Those two incidents initiated a frenzied 48 hours for Ohrt, acccording to an OPB report today, and he was later recognized for his efforts to save Mill City as the fires destroyed thousands of homes down the Santiam Canyon and across other parts of western Oregon.

Chief Ohrt saw Pacific Power’s utility lines start those fires, but he took the stand last week to defend the utility company in a class action trial against Pacific Power. He told a jury in Multnomah County Circuit Court that he immediately blew off attorneys who’d sent him paperwork in the weeks following the fires — lawyers who were trying to contact fire victims.

“I threw all that paperwork away,” Ohrt said. “You could tell right off the bat they were going to go after Pacific Power for this.”

Ohrt’s testimony highlighted a key aspect of the defense Pacific Power’s corporate owners, PacifiCorp, expect to lay out in the coming weeks of the trial: Most of the wildfires in the Santiam Canyon started not from their powerlines, but from embers of the Beachie Creek Fire. Even in places where powerlines did start fires, PacifiCorp’s attorneys contend that people fighting those fires quickly got them under control.

The defense follows what has been several weeks of plaintiffs’ attorneys alleging that PacifiCorp acted negligently by keeping its lines energized during the Labor Day fires, even though they had plenty of warning from weather officials and state government about fire danger. The decision to keep the power on contributed to fires spreading out of control, according to the plaintiffs and their attorneys.

Ohrt though, under questioning from PaficiCorp’s lawyers, pointed to another culprit: the U.S. Forest Service. Ohrt has more than 45 years’ experience with Mill City’s volunteer fire department, but he does not have any experience fighting wildfires.

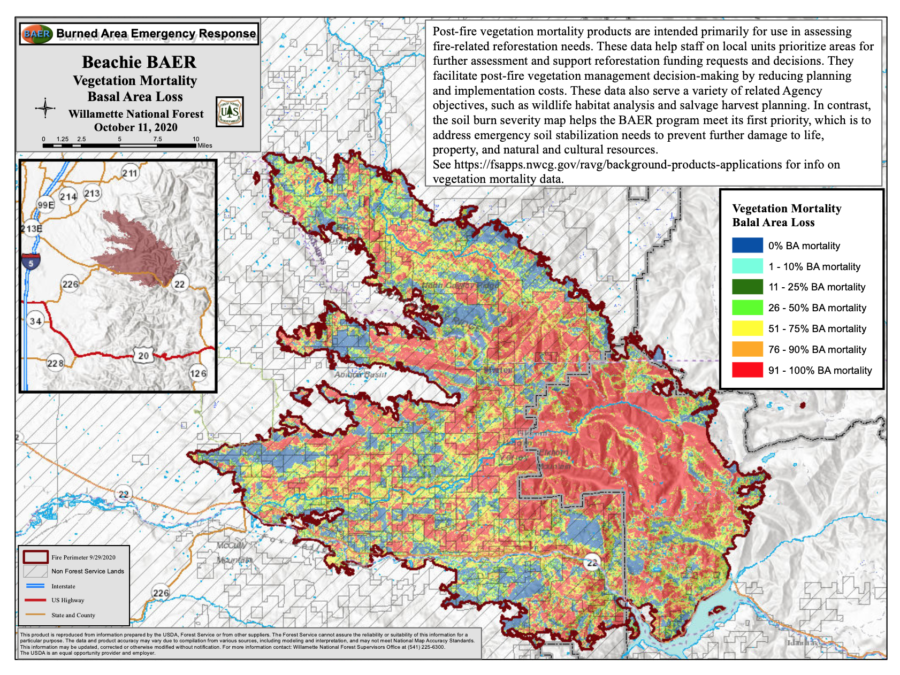

The inciweb images and maps and pages have been retired from the internet, but a few files remain on the Willamette NF site.

Weeks before the Santiam Canyon fires, a lightning strike started the Beachie Creek Fire — northeast of Gates in the Opal Creek Wilderness. Forest Service officials said then that steep terrain made it difficult to get crews to the site to contain the slowly growing fire. According to Ohrt, though, letting the Beachie Creek Fire smolder allowed it to throw embers into the Santiam Canyon when winds picked up on Labor Day.

An excellent “storymap” about the Beachie Creek Fire is [HERE].

“The U.S. Forest Service was supposed to be fighting that fire,” Ohrt said in his testimony.

Late in 2020 Linn County had to sue the Forest Service to get fire documents.

The Type 3 IC at the time knew that air support was critical, according to a USFS review of the fire, but he also recognized that the fire was burning in an old growth stand, meaning there was a multistory canopy with abundant down logs, duff, moss, and fuels. He knew that getting firefighters on the ground to dig deep for hotspots was the only way to successfully contain the fire.

“Everyone assumes that if you hammer a fire with aerial resources, it will go out, but that’s not the case. There needs to be boots on the ground working in tandem with aircraft. There are hidden hotspots, sheltered from aerial attack, under big logs and deep roots that have to be dug out.”

~ unnamed Type 3 Incident Commander

Whether jurors in the case find PacifiCorp responsible for the wildfires in the Santiam Canyon will likely be influenced by which attorneys’ experts they find more believable. Oregon State University professor John Bailey, for example, testified that there was no way the Beachie Creek Fire could have thrown embers far enough before midnight on Labor Day 2020 to start fires near the town of Gates. Bailey, who teaches fire management and has been studying forestry since the 1980s, said he used topography data, recorded weather conditions, and fuels analysis to estimate where the Beachie Creek Fire could have thrown embers ahead of its front to start new fires. He said strong east winds that night would have — at most — lit spot fires north of Gates and other residential areas in the canyon.

PacifiCorp’s attorneys, on the other hand, had atmospheric sciences professor Neil Lareau of the University of Nevada testify, and he said the extreme weather conditions that night did indeed throw firebrands miles ahead of the Beachie Creek Fire. Lareau explained to jurors how he used satellite data from the fire to determine when plumes of debris burst from the fire and cast embers thousands of feet aloft. He said those plumes matched up with on-the-ground reports of spot fires in the Santiam Canyon. Bailey, by contrast, said embers thrown by fires can rarely travel more than a mile — a far shorter distance than needed to start the fires Lareau claimed originated from the Beachie Creek Fire.

There were numerous powerline fires throughout Oregon during the Labor Day Firestorm. Oregon Department of Forestry along with local Fire Departments fought a number of these in Clackamas County with 3 of them each in the hundreds of acres in size. It seems very likely that there were powerline fires as well as spot fires from Beachie Creek in the Santiam Canyon and small towns west of the Canyon. But make no mistake, the majority of the 193,000 acres that burned was from the original Beachie Creek fire in the Wilderness. Another interesting point is that PGE shut down power in the Hoodland Corridor along Hwy 26 west of Mt. Hood sometime on Labor Day due to the predicted windstorm and fire danger. I was staying in a lodge overnight sunday before labor day and everybody received alerts on their cell phones of the power shutdown starting at 10 am on Monday. I don’t know what exact time they shut down power, but there were no major fires in the Hoodland Corridor.

Looks like 1967. https://www.nwcg.gov/committee/6mfs/sundance-fire

USFS do the aerial attack! You have the equipment to reveal hot spots after the spray. You also have helitack crews and smokejumpers for remote areas. There is no need for allowing fires to go unattended burning homes and towns.

I’m a smokejumper. I was on the jumpship looking down on Beachie when it was reported. We did respond. Trust me, we wanted out of the plane to fight it, we always do. If it was even a possibility that we could have safely jumped it, we would have. It pains me to continually see people who do not know what they’re talking about spread slanderous filth about the way Beachie was managed. It’s like telling Mickey Mantle, in 1960, that I know more about hitting homeruns than he does. I know the people who manage fire on this portion of the Willamette NF. They are some of the most experienced fire managers out here!…former jumpers and hotshots themselves, and into their 3rd or 4th decade of doing it. They used every tool in the toolbox to get after it. Jumpers turned it down, rappellers turned it down, hotshots turned it down. Beachie blew up and became what it became. Armchair quarterbacking does nothing but expose the speakers ignorance.

Have you thought about the fact that with no safe access to fight the fire, the entire N Fork Santiam drainage was evacuated? That had we extinguished Beachie, said drainage would have been filled with 500-1000 folks enjoying their camping that Labor Day weekend? That the night when Beachie was making its run to the west, the same eastwinds driving Beachie were pushing Lionshead. Lionshead would have blown thru said drainage at a time when most would have been sleeping. Any fatality is a tragedy; what about hundreds? Hypocriticals are endless. It gets us nowhere.

I have been part of some really hairy and sketchy situations in my profession, so hear me when I say – one or many of us would have likely been killed going direct on it. Our society wants to talk like fire is war, but we’re not willing to accept the costs, not monetarily, not culturally, not societally. Please realize the added shame and guilt you place on us with your misinformation. It’s another brick or two on the shoulders of us underpaid, overworked, understaffed, and unappreciated federal wildland firefighters. Pride and service is the only reason some of us stay – so keep it up, one day they’ll throw a fire and nobody is going to show up.

The record for long distance spotting is the Pack River fire near Sandpoint, Idaho. Nine miles from the main fire !

But the typical long distance. spot fire is one mile +/-.

What year was that, John?

The 2020 Oregon firestorm was not typical, it was a once in a lifetime event(hopefully)! Fire behavior and spotting distance models were not capable of predicting behavior and spotting distance. I tried using Behave on the 2014 36 Pit Fire that spotted 1 mile at night with 20-30 mile per hour winds and it couldn’t get to even a mile. I can believe that Beachie spotted well over a mile during the 50-60 mile per hour firestorm conditions that first night.

Please let us know about the results of this trial. As a person who lost his home to a fire that was started by PG&E’s lack of vegetation management in the ’90s and knowing the Forest Service’s habit of letting small fires smolder while being ‘monitored’ (ie: 68,637 acre Tamarack Fire in 2021) I’ll be very interested to see how this turns out.

Thank you.