A group of people knowledgeable about wildland fire have produced a 52-page document that attempts to assemble and summarize areas of agreement and disagreement regarding the management of forested areas in the western United States. Calling themselves the Fire Research Consensus Working Group, they looked for areas of common ground to provide insights for scientists and land managers with respect to recent controversies over the role of low-, moderate-, and high-severity fires.

Their report is titled, A Statement of Common Ground Regarding the Role of Wildfire in Forested Landscapes of the Western United States.

Here is how they hope their conclusions will be used:

Our hope is that stakeholder groups will avoid the selective use of particular scientific papers to argue for their particular ends. Instead, they will be able to point to key shared assumptions, common understandings considering the entire body of fire science literature, and terminology to support decision-making in constructive ways. In particular, land and fire managers are a key audience for this report, as are other stakeholders and the interested public engaged in discussions about land management.

The “Executive Summary” is 6 pages long. Below is the section about high-severity fire:

“Respondents disagreed about whether large, high-severity fires have increased to a significant and measurable degree in all forest types in comparison to historical fire regimes (i.e., prior to modern fire suppression). There was strong agreement that in dry pine forests at low elevations there has been either an observed increase in high-severity fires or an increase in the potential for fires of elevated severity as the result of increased abundance and connectivity of woody fuels since the late 19th century. There was similar strong agreement about dry mixed-conifer forests in the Inland Northwest, Pacific Southwest, and Inland Southwest (Arizona and New Mexico) that there has been an increase in high-severity fires and an increase in the potential for fires of elevated severity. There was less agreement about the changes in extent, and causes of changes in extent, of high-severity fires in moist mixed-conifer forests. Although there is general agreement that high-severity fires historically played an important role in moist mixed-conifer and cold subalpine forests, there is strong disagreement over the degree of changes in burn severity patch-size distributions and associated successional conditions for these forests between different regions.

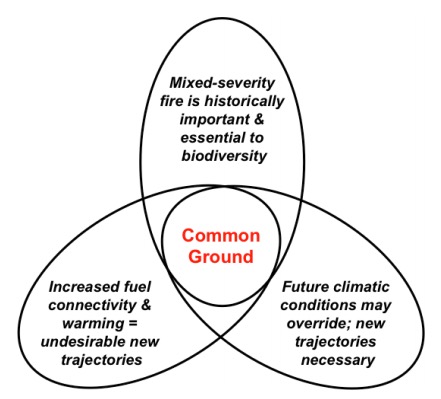

“Opinions also vary over the consequences of any increases in fire severity. For most dry forests, although there may be some disagreement about trends in burn severity and their causes, there is broad agreement that under current and projected climate, post-fire forest resilience is less than in the past. Some forest habitats, particularly at drier sites, but also in some moist and cold forest sites, show evidence of converting to more flammable non-forest vegetation or less dense forests following recent fires where large patches burn severely, especially if reburned. Reburn potential may depend on the interaction of vegetation, weather, rate of fire spread, time since prior fire, ignitions and fire suppression. Opinions are varied concerning the ecological consequences of departures from historical patterns of fire severity in various mixed conifer and subalpine forests. For example, one viewpoint supports the historical precedence of mixed-severity fire (including relatively large patches of high-severity fire), and the concept that pyrodiversity begets biodiversity. Another viewpoint asserts that increased woody fuel connectivity in combination with a warming climate trend is setting large areas of landscapes on fundamentally new trajectories, with significant undesirable ecological and societal consequences. Still a third viewpoint emphasizes that climatic changes increasingly are of overriding importance, and that new trajectories are unavoidable and thus may be considered desirable in many cases to incrementally foster necessary ecosystem transitions. The figure below characterizes these divergent viewpoints – typical of many areas of disagreement we addressed – and the potential common ground among them.

“Uncertainties associated with relative proportions of different burn severities and patch-size distributions combine to cloud key points of consensus that have important management implications. We suggest that resolving many fire science disagreements depends on greater consideration of specific geographical context. This may imply that a narrow range of field experience can limit one’s ability to accept findings that depart from that range. A logical way forward is to increase in-depth cross-regional field research experiences of the fire research community. Cross-regional comparisons of top-down and bottom-up determinants of fire activity in similar forest cover types is a fertile area of future research to examine how differences in seasonality, productivity, understory fuels, land use history, and other factors may explain some of the reported geographical differences in historical fire regimes in broadly similar forest types.

“There are several reasons for the disagreements about the amount and roles of past higher-severity fire. Both scientists and managers often transfer concepts and findings from one place to another, yet we know that “no one size fits all” for historical fire regimes, even within the same forest type. Likewise, the extent of change in abundance and connectivity of woody fuels varies across forest types and ecoregions. Some of the disagreement derives from use of different scientific approaches. For instance, there is strong debate about the fire regime inferences made from historical and modern tree inventory data, simulation models, and other approaches. We believe that application of diverse research approaches will be useful going forward. Further, multiple approaches will be useful in “triangulating” interpretations for which there is some scientific consensus (see Topic H). We challenge fire scientists who do not share similar perspectives on historical fire regimes in particular ecosystems to engage in civil discourse to better understand the reasons for their disagreement, and to objectively communicate those reasons to managers and other stakeholders. We are heartened by the positive outcomes achieved by some previous attempts when small or large groups work together to find common ground.”

Moritz, M.A., C. Topik, C.D. Allen, P.F. Hessburg, P. Morgan, D.C. Odion, T.T. Veblen, and I.M. McCullough. 2018. A Statement of Common Ground Regarding the Role of Wildfire in Forested Landscapes of the Western United States. Fire Research Consensus Working Group Final Report.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Ben.

Typos or errors, report them HERE.