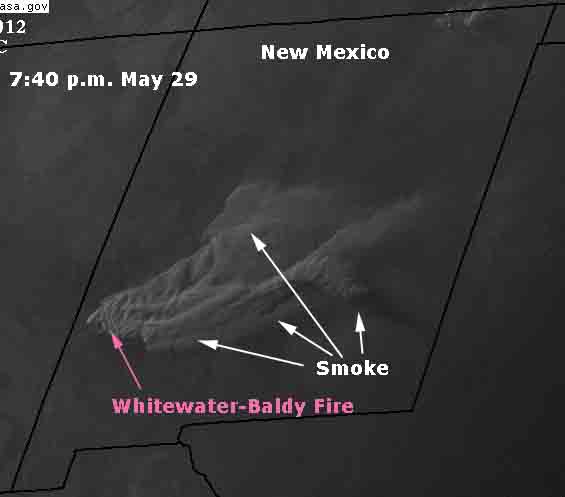

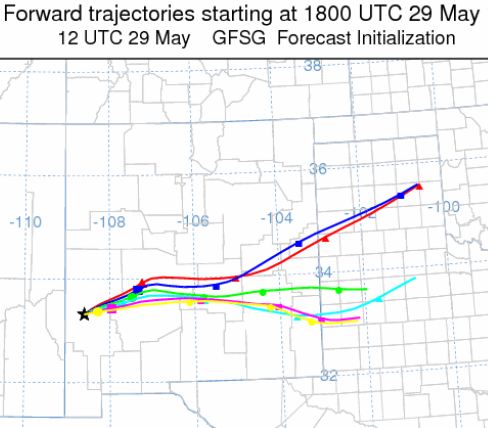

U.S. Representative Steve Pearce has assembled five reports about two huge wildfires, megafires, that burned hundreds of thousands of acres and destroyed many homes in New Mexico in 2012. The Whitewater Baldy Complex blackened over 297,000 acres and destroyed 12 summer homes, while the Little Bear Fire burned 44,000 acres and 254 structures.

In June, 2012, Representative Pearce was extremely critical of the way the U.S. Forest Service was managing the fires, mentioning the name of Tom Tidwell, Chief of the Forest Service, many times during a 22-minute speech on the floor of the House of Representatives.

In June, 2012, Representative Pearce was extremely critical of the way the U.S. Forest Service was managing the fires, mentioning the name of Tom Tidwell, Chief of the Forest Service, many times during a 22-minute speech on the floor of the House of Representatives.

The five reports, plus one bonus article from the 1940s, can be found on Representative Pearce’s web site, and include the following:

- William A. Derr, retired as Special Agent in Charge of the Law Enforcement and Investigative program in California. Mr. Derr was asked by Rep. Pearce to evaluate the management of the two fires, and was given the title of Legislative Fellow during his fact finding mission. It was an unpaid assignment, and Mr. Derr told Wildfire Today that he is not even sure if he will ask to be reimbursed for his travel expenses.

- Roger Seewald, retired from the U.S. Forest Service, began his career in wildland fire on the El Cariso Hot Shots in California, and after a decade or two switched over to law enforcement. At one point late in his career he worked out of the Washington office as Deputy Director, Law Enforcement and Investigations. In his report he stated he was representing the U.S. Forest Service. In Mr. Derr’s report he was described as “representing the Chief of the Forest Service”.

- Doug Boykin, Socorro District Forester, New Mexico – Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, Socorro District. Mr. Boykin was the Type 3 Incident Commander during one of the early stages of the Whitewater Baldy Complex. He wrote a 17-page report packed with details and photographs. One of those details that is surprising for an objective report by a government employee about a disastrous wildfire, is that he apparently thinks God controlled the fire, and wrote: “But, given what we know now, I feel this was the perfect set up by a higher power that had grown tired of our inability to use common since [sic] in forest management and chose to set things right in his own way.”

- Allen Campbell, a local resident and rancher who spent his early years “guiding clients”. His report covers the legacy and the environmental impacts of the fire, and is critical of the USFS fire management policy.

- Impact DataSource, is an economic consulting, research, and analysis firm working out of Austin, Texas. Their report is titled “The Full Cost of New Mexico Wildfires”. The purpose of the report was to “…estimate the full impact of wildfires in New Mexico both during and after the wildfire occurs.” And, “…additional environmental,societal, economic and fiscal impacts are typically not tracked by any federal, state or local government or organization making the full impact of wildfires difficult to quantify.”

- Earl W. Loveridge, formerly the Assistant Chief of the USFS, and before that the Assistant Chief of it’s Division of Operation and Fire Control. This reprint of a Journal of Forestry article appears to have been written in the mid-1940s. Chief Loveridge covered fire management policy, was critical of a “let burn” strategy, and pointed out the “importance of speed of control”. He also covered the 1935 origin of the “10 a.m. policy”, in which “Forester” F. A. Silcox stated, in part:

- “The approved protection policy on the National Forests calls for fast, energetic and thorough suppression of all fires in all locations, during possibly dangerous fire weather. When immediate control is not thus attained, the policy then calls for promptly calculating of the problems of the existing situation and probabilities of spread, and organizing to control every such fire within the first work period. Failing in this effort the attack each succeeding day will be planned and executed with the aim, without reservation, of obtaining control before ten o’clock of the next morning…. No fixed rule can be given to meet every situation; the spirit implied in the policy itself will determine the action to be taken in doubtful situations.”

The management of both fires, the Whitewater Baldy and the Little Bear, has been criticized. The Whitewater Baldy began as two fires, the Whitewater and the Baldy fires, which burned together. The Baldy was a “modified suppression” fire and was monitored, but the Whitewater was managed under a suppression strategy.

Much of the criticism of the Little Bear fire, including from Wildfire Today, was focused on what appeared from a distance to be less than aggressive suppression tactics, even though it was a suppression fire. Two firefighters worked the fire on the first day, and from day two through day five, while the fire was only four acres, a hotshot crew was assigned, but they had very, very little aerial firefighting support; limited use of one helicopter and no air tankers. On the fifth day the wind increased, a tree in the interior of the fire torched, and spot fires took off. The fire grew from 4 acres to 44,000 acres and destroyed 254 structures.

Mr. Derr’s report does not dig into the tactics of the fires, but concentrates primarily on the fire management policy of the USFS. He is critical of less than aggressive strategies, and regrets the abandonment of the 10 a.m. policy.

Mr. Seewald visited the four-acre site that comprised the Little Bear Fire for the first 5 days and cited steep slopes, heavy downed fuel, tree canopy, and rolling rocks as issues that made aerial support inadvisable, and for any more than one crew of firefighters to work the fire. He concluded that the USFS “…made every reasonable effort to extinguish the Little Bear Fire and used acceptable methods and strategies to control the fire.” He found very little to criticize other than suggesting that the USFS could “revisit” the methods used for communicating with the public and cooperators.

The Seewald report said the strong winds that caused the spot fires to take off were not predicted in the spot weather forecasts provided to the firefighters.

Doug Boykin, the Incident Commander on the Whitewater Baldy Fire, believes that the decisions about management of the Whitewater and the Baldy fires were appropriate, after taking into consideration the firefighting resources available, weather, fuels, and topography. Mr. Seewald, while he did not say so explicitly, seemed to agree with that assessment.