There are at least 39 published studies about the effects of bark beetles on wildland fire behavior. With such a bounty of government-funded work, you could hope that we would have some definitive answers, but unfortunately, while there is some agreement among the studies, there is substantial disagreement on some key issues, including the impacts of beetle-caused tree mortality in key areas such as fire behavior during the red needle phase, which is typically one to four years after a beetle attack.

This was one of the conclusions in a recent study that analyzed 39 other published works about the effects of pine beetle mortality. It is titled Effects of bark beetle-caused tree mortality on wildfire, and was written by Jeffrey A. Hicke, Morris C. Johnson, Jane L. Hayes, and Haiganoush K. Preisler.

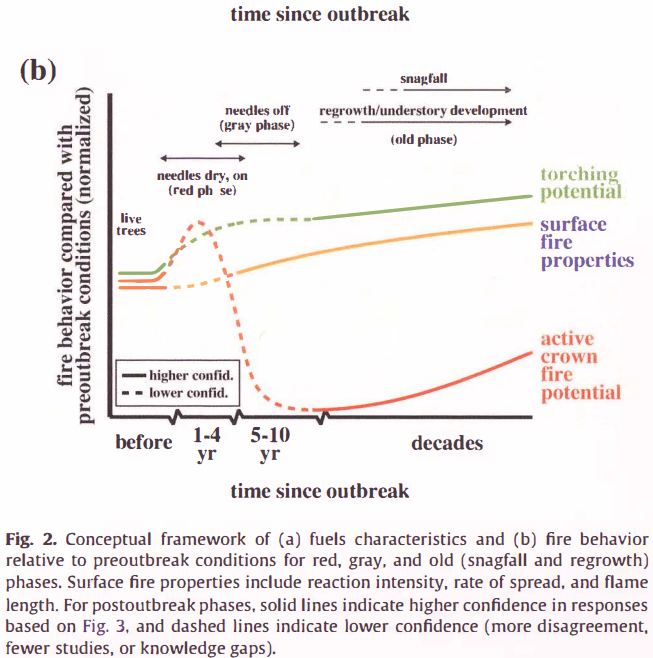

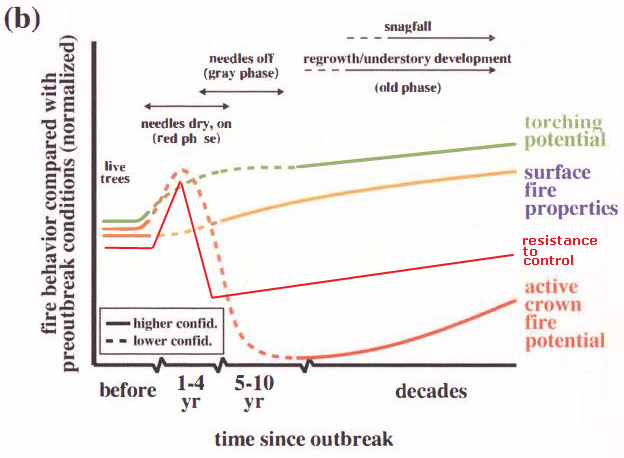

The chart below is from their paper.

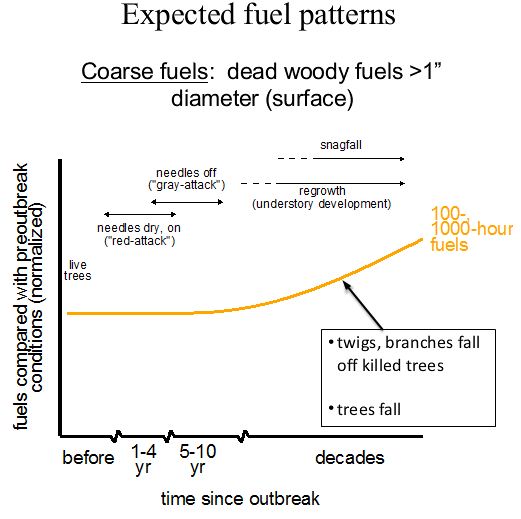

The author’s confidence in the conclusions reached about torching potential and active crown fire potential for the first ten years was low, but it is probable that active crown potential would increase for the first four years after mortality and then decrease dramatically. Torching potential would probably increase.

Surface fire properties, defined as reaction intensity, rate of spread, and flame length, would likely increase, but the confidence in the prediction for the first four years was low.

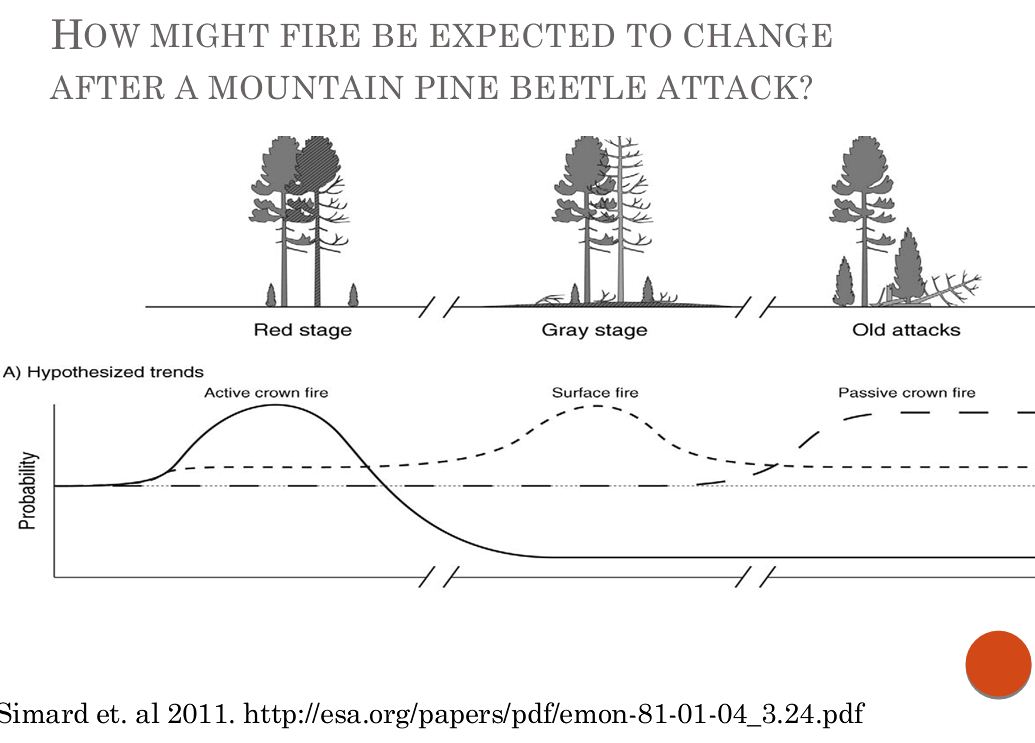

The authors pointed out that changes in fire behavior following a pine beetle outbreak…

…may only occur under some environmental conditions. For example, effects may be manifested during intermediate wind speeds (Simard et al., 2011) or in moister conditions, such as earlier in the fire season (Steele and Copple, 2009). Past controversy on this topic can be partly reconciled by this consideration of more specificity about study question, time since outbreak, and fuels or fire characteristic when describing results.

Our view of the research

It would be helpful if all of these parameters and studies could distill the conclusions into one index, which I will call Resistance To Control (RTC). Simultaneous increases in surface fire, torching, and crowning would result in more RTC. But it becomes more complicated to characterize when, for instance, crown fire potential decreases to near zero, while surface fire intensity and torching increase. Long distance spotting is a firefighter’s biggest headache and makes fires almost impossible to control, at least at the head. Crown fires are the major culprit for long distance spotting, but surface fires and individual or multiple tree torching can also create spot fires. And all of this varies, of course, with the weather. Strong winds can make ANY fire very resistant to control as long as the fuels are continuous.

If a person leaps to the possibly incorrect conclusion that all of the fire behavior parameters shown in the chart above are accurate, including the sections with low confidence, then RTC would increase one to four years after a beetle outbreak, and then would probably decrease since the crown fire potential would dramatically decline. Surface fires, including those with some torching, can be more easily controlled using tactics, sometimes with aerial support, such as direct hand line construction, hose lays, indirect line construction with burnouts, and backfiring from out ahead of the fire. When crowning is the primary method of fire spread, you usually have to wait for either the weather or the fuels to change. Air tankers and helicopters dropping fire retardant or water can be more effective when the fire is confined to the surface, as long as firefighters are on the ground to take advantage of the temporary slowing of the rate of spread, and if the wind is not too strong.

With apologies to the authors of this very good research paper, I took the liberty of adding a Resistance To Control variable to their chart:

And of course the authors of the paper included the familiar phrase, “more research is needed”, which is a mandatory section in every research paper.

The authors, who are employed by taxpayers, arranged to have the government pay a fee to have their paper published by the for-profit Elsevier corporation which is headquartered in the Netherlands. But thankfully, this time the USFS also published it on their U.S. Government web site where taxpayers can access it at no additional charge.

If you believe taxpayer-funded research should always be available to taxpayers freely over the internet, go to the White House web site and sign the petition. (Update Jan. 23, 2013: you can still read the petition at the site, but it is closed to new signers.)

Thanks go out to Tom, who, in a comment on another article on Wildfire Today about bark beetles, pointed out this new research paper.