Northern California’s first major fire of the year has burned 12,500 acres in San Joaquin County. The Corral Fire started Saturday afternoon near the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Site 300, and CNN reported that the fire started in the city of Tracy.

Two Alameda County firefighters were injured, Cal Fire Battalion Chief Josh Silveira told CNN on Sunday. They had minor to moderate injuries and were transported to a local hospital.

UPDATE: 14,170 acres Sunday evening; the Associated Press reported 50 percent containment and one home destroyed.

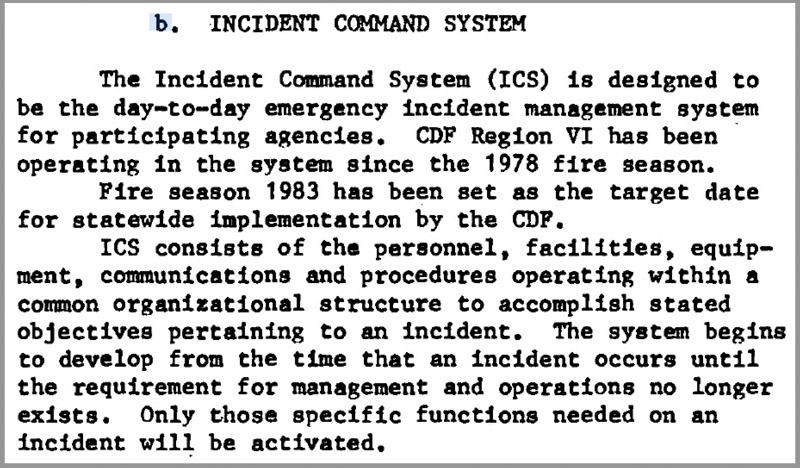

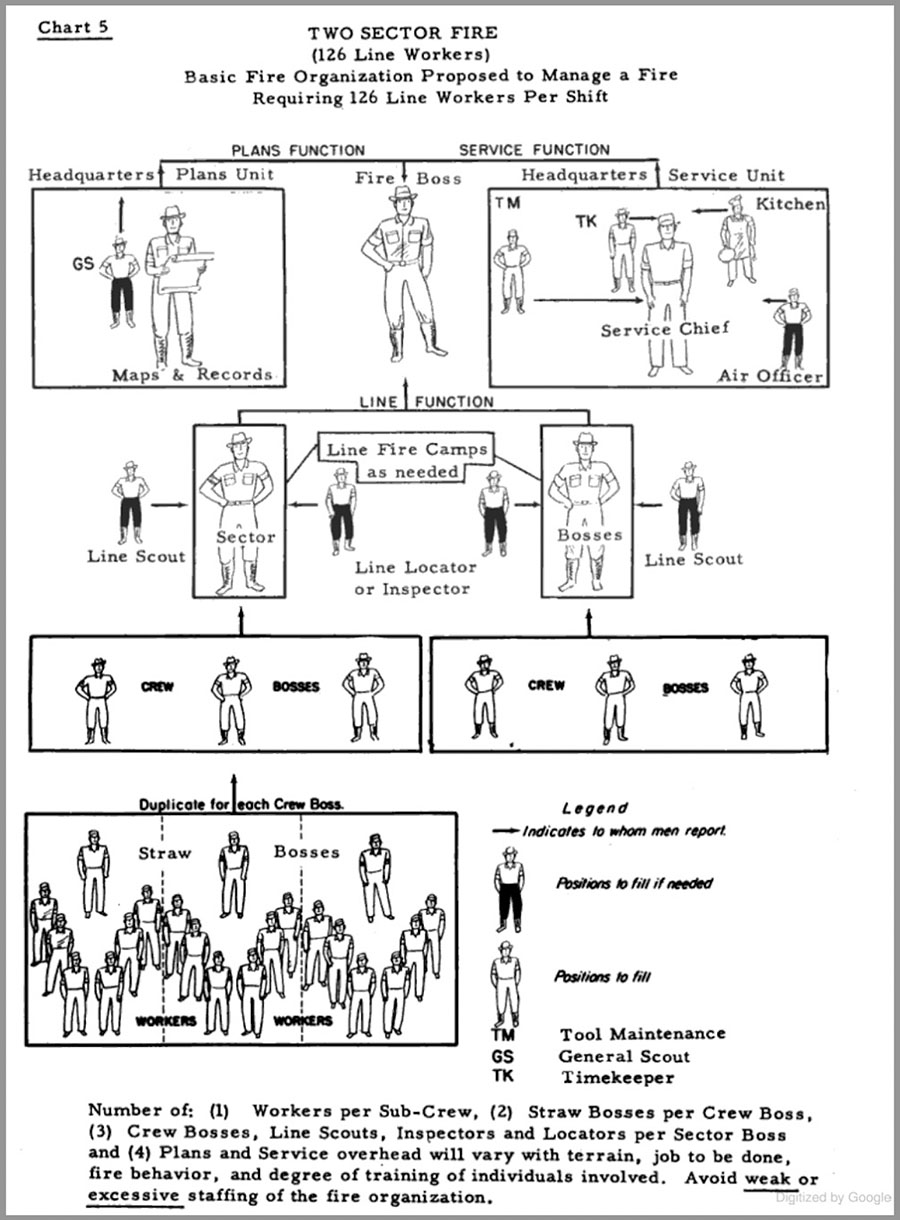

The fire was at 15 percent containment this morning, according to Cal Fire, and fire managers said the gusty winds and dry grass have made it difficult to contain. About 400 people are assigned on the fire 60 miles east of San Francisco. ABC10.com has aerial images.

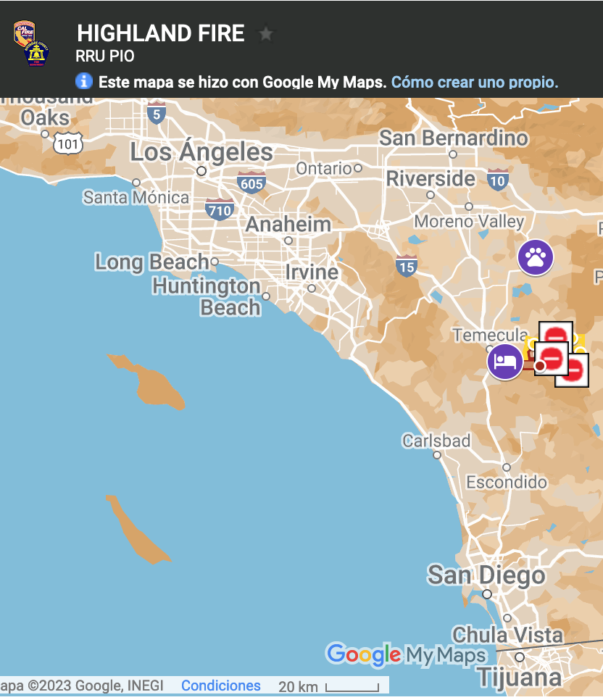

San Joaquin County Office of Emergency Services ordered residents to evacuate, as sfgate.com reported, and an evacuation map from the county is [HERE]. Interstate 580 is closed from 4.7 miles east of the junction of State Route 132 at Gaffery Road to the San Joaquin-Alameda county line; smoke has reduced visibility to “zero” according to Caltrans.

The Sacramento Bee reported this afternoon that both sides of I-580 had been re-opened. Caltrans officials said one eastbound lane would remain closed between I-205 and I-5 to buffer firefighting traffic; Highway 132 was also reopened after it was shut down for about 17 hours.

The Corral Fire grew rapidly after 7 p.m. Saturday and Cal Fire said it was at 5,000 acres and 40 percent containment; a few hours later, containment dropped to 13 percent and the fire doubled in size.

The cause of the fire is unknown. The New York Times reported that residents were prohibited from burning anything on their own properties, and fire officials for the Santa Clara area announced that all burn permits in the region would be suspended beginning Monday. Lawrence Livermore National Lab said the fire started near the lab’s Site 300 but was not related to controlled burns conducted there.

“LLNL recently completed a series of controlled burns to eliminate dangerous dry grass areas and provide buffer zones around Site 300 buildings,” said Michael Padilla, deputy director of public and media relations. “There are no current threats to any Laboratory facilities and operations as the fire has moved away from the site. There was no on- or offsite contamination.”

Site 300 is a testing location at which researchers “formulate, fabricate, and test high-explosive assemblies to assess the performance of nonnuclear weapon prototypes and components.”