Fighting wildland fires as we have known it is likely to go through a transformation during the next 6 to 18 months. As the COVID-19 pandemic begins to reach into more segments of the daily human existence the way we suppress wildfires may have to be modified.

Obstacles to firefighting

At a White House briefing on March 16 the President and Dr. Anthony Fauci said people should not assemble in groups larger than 10 and recommended “Social distancing”– spacing between individuals needs to be at least 6 feet. Being near any infected person, even if it is just one person, runs the risk that droplets expelled from their mouth or nose, or viruses on their face, hands, or clothing could be transferred to others. Without widespread testing, it is impossible to know if someone is infected without being symptomatic. The symptoms, if they occur at all, may not develop for days.

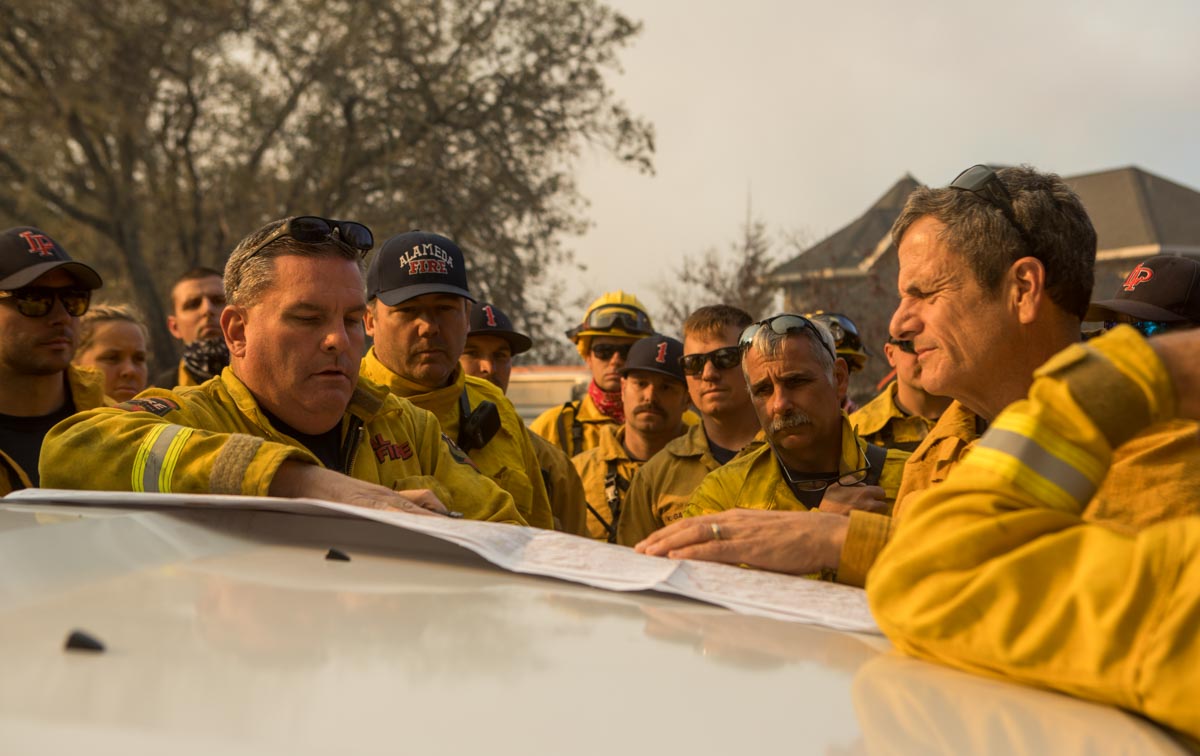

Social distancing would be extremely difficult to maintain while traveling to or extinguishing a fire. Wildland firefighters are trained to never work alone, and are always in groups ranging from 2 on a small Type 6 engine, 20 on a hand crew, and hundreds or thousands while assigned to a large fire. On Tuesday multiple engine crews battled three fires that burned 50 acres near Foxton in Jefferson County, Colorado about 20 miles southwest of Denver. On March 6, 286 firefighters responded to a 20-acre fire in the Cleveland National Forest near Lakeland Village in southern California. In 2017 more than 8,500 firefighters were assigned to the Thomas Fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties in southern California.

Time

This is not like dealing with climate change that over years and decades has slowly caused fires to grow larger. A rapidly growing pandemic that kills approximately 0.7 to 3.0 percent of those infected means we don’t have the luxury of time to come up with solutions. A new scientific report warns that without action by the government and individuals to slow the spread and suppress new cases, 2.2 million people in the United States could die.

The March 1 outlook for wildland fire potential predicted higher than average fire activity during March and April in the coastal areas of Central and Southern California.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE

Prevent fires

It is possible that with social isolation the number of human-caused ignitions will decrease. Or, will campfires in the woods increase when folks get cabin fever and have more time on their hands? Fire prevention efforts have to increase, with more public service announcements and prevention officers in the field.

Reduce the number of fires that escape initial attack

The fewer large fires we have that require hundreds or thousands of firefighters to work together, the safer firefighters will be from additional virus exposure. This would also reduce evacuations that can result in refugees assembling in large numbers. An infected person forced to leave their self-quarantine to fend around for housing is a danger to society.

How to keep fires from becoming large

There is no silver bullet that can guarantee a fire will not escape initial attack, but the most effective tactic is:

This means, if there is a report of a fire, don’t just send one unit out to verify unless you have a very good reason to suspect it is a false alarm. Dispatch overwhelming force — engines, crews, helicopters, and air tankers. This is not inexpensive, but can save millions of dollars if it keeps a fire from growing large.

The need for more firefighting resources

Congress is considering a proposal to spend $1 trillion dollars on a stimulus package to combat the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic, according to a proposal obtained by NBC News. A trillion is a number that is nearly impossible for me to comprehend. It is a thousand billion. A billion is a thousand million.

If more firefighters were hired it could make it possible to have healthy forces in reserve when 20-person crews or 5-person engines have to be quarantined when one crew member tests positive for the virus or if they are exposed while fighting a fire. It could also enhance the ability to attack new fires with overwhelming force.

Since firefighters assembling in groups to suppress a fire can put them at risk of spreading COVID-19, we need to rethink our tactics. This could include making far greater use of aerial firefighting. It should become standard operating procedure to have multiple large air tankers and helicopters safely and quickly attacking a new fire from the air, far from any people on the ground infected with the virus.

In 2002 there were 44 large air tankers on federal exclusive use (EU) contracts. Last year and at the beginning of this year there are only 13. That is a ridiculous number even in a slow fire season like last year when 20 percent of the requests for large air tankers were unfilled. The number of acres burned in the lower 48 states in 2019 was the least since 2004.

There are so few large airtankers on EU contracts that dispatchers have to guess where fires will erupt and move the aircraft around, like whack-a-mole.

The U.S. Forest Service says they can have “up to” 18 large air tankers on EU contract, but that will only be possible if and when they finally make awards based on the Next-Generation 3.0 exclusive use air tanker solicitation that was first published November 19, 2018. There are an additional 17 large air tankers on call when needed (CWN) contracts that can be activated, but at hourly and daily rates much higher than those on EU.

If multiple large air tankers and helicopters could attack new fires within 20 to 30 minutes we would have fewer large fires.

Congress needs to appropriate enough funding to have 40 large air tankers on exclusive use contracts. Until that takes place and the aircraft are sitting on ramps at air tanker bases, all 17 of the large air tankers on call when needed contracts need to be activated this summer. Right now, only one large air tanker is working.

Several years ago the number of the largest helicopters on EU contracts, Type 1, were cut from 34 to 28. This number needs to be increased to 50. Until that happens 22 CWN Type 1 helicopters should be activated this summer.

We often say, “air tankers don’t put out fires”. Under ideal conditions they can slow the spread which allows firefighters on the ground the opportunity to move in and suppress the fire in that area. If firefighters are not nearby, in most cases the flames will eventually burn through or around the retardant. During these unprecedented circumstances brought on by the pandemic, we may at times need to rely much more on aerial firefighting than in the past. And there must be an adequate number of firefighters available to supplement the work done from the air. It must go both ways. Firefighters in the air and the ground support each other.

All firefighters need to be tested for the virus at regular intervals

If firefighting crews have to isolated and put on the sidelines because one member develops COVID-19 symptoms, it is likely that they had already been shedding the virus for days, possibly infecting others.

The small town of Vò in northern Italy where the first COVID-19 death occurred in the country, has become a case study that demonstrates how scientists might neutralize the spread of the disease. On March 6 they began a program to test all 3,300 inhabitants of the town twice, including asymptomatic people. Those without symptoms that tested positive were isolated, as were those with symptoms of course, and since then there have been no new cases.

This lesson is being learned. San Miguel County in Colorado, the location of Telluride, will be the first county in the U.S. to test every resident.

If we expect to maintain wildland firefighting capability, every firefighter must be tested on a regular basis. This can greatly reduce the risk when they gather in large numbers to suppress a fire.

Other key members of the wildland firefighting community must also be tested in order to maintain the viability of the system. This would include pilots, aircraft mechanics, air tanker base crews, helitack crews, dispatchers, members of Incident Management Teams, and contractors that supply firefighting equipment and services, especially caterers.

Should we still manage “limited suppression” fires?

In the last 10 years we have seen more wildfires allowed to spread with only limited suppression. These fires can persist for months while they are being baby sat by firefighters. Yes, there are benefits to the natural resources to allow fire to run its natural course. Fewer personnel are used early in the fire, but the amount of time involved results in them being tied up for an extended period. And if a month or two into it, after it has grown large and has to be suppressed, then you will need a huge commitment of forces. If firefighting resources are extremely limited by the effects of the pandemic, the second and third order effects of this strategy need to be thoroughly examined by smart managers before they decide to not aggressively attack a new fire.

Area Command Teams activated

Three Area Command Teams (ACT) have been activated in the United States to assist in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The delegation of authority directs them to coordinate with Federal, State, local, and Tribal officials to identify issues related to COVID-19 and wildland fire response. They will develop fire response plans for maintaining dispatching, initial attack, and extended attack capability. The ACTs will also develop procedures or protocols for mitigating exposure to COVID-19 during an incident, and for responding in areas with known exposure to COVID-19.

This is an important and necessary step. We are in uncharted territory, and no one has ever fought wildland fires under these conditions, at least in the United States.

Table top exercises or simulations

They may already exist, but if not, table top exercises could be very useful for Regional and National Multi-Agency Coordinating Groups to work through the steps of allocating firefighting resources that in a worst case scenario could become scarce on an unprecedented scale. Maybe a billionaire or video game designer will develop a computer-based simulation for this purpose.

Yes, this is a lot — 40 EU large air tankers, 50 EU Type 1 helicopters, initial attack with overwhelming force, and testing for everyone involved in firefighting.

We need to be in this for the long haul. No one knows for sure, but scientists are thinking that this new virus will ebb and flow. The spread may peak every few weeks and it may or may not slow in the summer, but will most likely peak again in the fall and winter well into 2021. There is no known cure and it will be at least 12 to 18 months before a vaccine is available.

But what is the alternative? If our firefighters are isolated, quarantined, or deceased, there could be a lot of smoke in the skies this year that will exacerbate respiratory diseases being suffered by many.