The Chief of the U.S. Forest Service has laid out some very broad guidelines about how the agency will approach fire management during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a letter to Regional Directors dated April 3, 2020, Chief Victoria Christiansen said one of the objectives during this fire year will be to minimize the exposure from the virus and smoke to firefighters and communities. Local resources will be prioritized and the predominant strategy will be rapid containment, Chief Christiansen said.

Additionally, resources should be committed to fires “only when there is a reasonable expectation of success in protecting life and critical property and infrastructure.”

Additionally, resources should be committed to fires “only when there is a reasonable expectation of success in protecting life and critical property and infrastructure.”

Click here to read the full letter from Chief Christiansen.

Kari Cobb, a Public Affairs Officer with the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise told us about some steps the federal wildland fire agencies are considering:

- Hiring more seasonal employees than usual to help reduce risk;

- Focusing on aggressive initial attack to quickly contain fires while relying more on aviation and local resources;

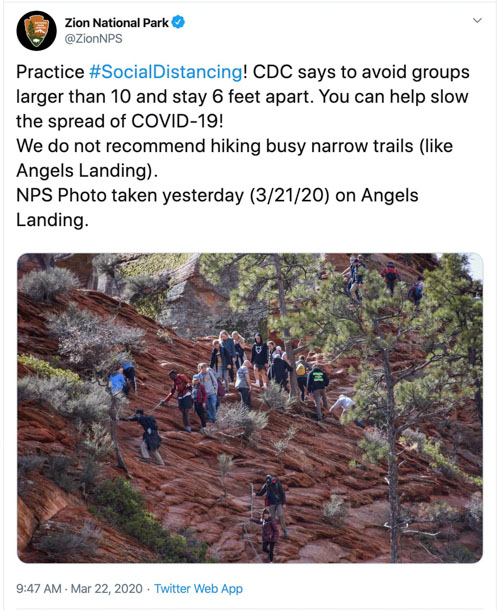

- Social distancing by unit, without traditional fire camps and with quarantines both before and after fires;

- Deploying resources in a way that minimizes travel to other geographic areas;

- Where feasible, increasing technology use through virtual work to reduce the risk of exposure to the coronavirus;

- Setting up systems for screening, testing, quarantining, and tracking our firefighters;

- Tailoring the way we communicate and coordinate with our workforce, partners, cooperators, and the public to the novel risks we face this year; and;

- Shifting our workloads to respond to COVID-19, protect the public, and safely manage wildland fire throughout the fire year.

Area Command Teams

As we first reported on March 17, the National Multi-Agency Coordinating Group (NMAC) has assigned three Area Command Teams to work with partners at all levels in the fire community to develop protocols for wildfire response during the COVID-19 pandemic. The protocols will be integrated into Wildland Fire Response Plans and will be available to Geographic Areas, Incident Management Teams, and local units to help guide effective wildfire response. The Teams will also be working with and following guidance from federal, state, county and tribal health officials. Area Command Teams are working directly with NMAC and agency representatives; Geographic Area Coordination Groups; the National Wildfire Coordinating Group; dispatch and coordination centers; local units; and federal, state and county health officials as appropriate to ensure thorough and current wildfire response plans are in place.

Response plans will include procedures for potential wildland fire personnel infection, which will be led by the local State Health Department following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance and protocol.

Annual training and fitness tests

The Fire Management Board reported last week that Work Capacity Tests, including Pack Tests, are suspended in 2020 for some returning employees.

The annual refresher training, RT-130, is also not required this year. Instead, employees are encouraged to complete a self-study refresher utilizing the WFSTAR videos and support materials. The Board recommends that the study include topics that focus on entrapment avoidance, related case studies, current issues, and other hazards and safety issues.

Many training events, meetings, and conferences that had been scheduled for months have been cancelled or postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Will firefighters be tested for COVID-19?

We asked Kaari E. Carpenter, a Lead Public Affairs Specialist with the Forest Service if wildland firefighters would be tested for the virus. She told us, “Specific risk-based protocols for how we will respond will be developed at the field level by line officers and through the National Multi-Agency Coordinating Group.”

Ms. Carpenter said no Forest Service firefighters have tested positive for the virus or died from COVID-19. She did not say how many have been tested.

Leadership defers some COVID-19 decisions to field level

When asked if firefighters are still reporting for duty at their fire stations, Ms. Cobb replied, “Specific risk-based protocols for how fire stations are being staffed is developed at the field level by line officers and can vary by location.”

Our take

It is hard for me to conceptualize how small, medium, and large wildfires can be safely suppressed during this pandemic. Wildland firefighting in the best of times is one of the more hazardous occupations, but now, with no treatment, widespread testing, or vaccines for COVID-19 firefighters will be risking their lives at another level by working together as they always have. The three Area Command Teams have been laboring for 17 days to develop protocols for managing a wildland fire department during the pandemic, so it will be interesting to see what they are able to develop.

In a couple of examples above, important decisions about the health and safety of federal employees are being punted. Instead of leaders making tough decisions about how to protect personnel they are backing away and ordering them to be made at the field level. Leaders at the highest level should be making decisions about how to utilize testing, for example. Leaders at the Department or White House level should have the authority and responsibility to order that tests be made available for all wildland firefighters on a recurring basis. This is not a field level decision. The Area Command Teams should make this their Number One Recommendation. But firefighters ought not to have to wait for the Teams to put this in writing. Testing should have been implemented a month ago.

Time is being squandered.

Epilogue

The administration is keeping a very close handle on information about how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting wildland fire management in the federal agencies. All of Wildfire Today’s official inquiries are passed along a chain that goes up to the headquarters of the agencies in Washington and then further, to the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. Due to the laborious approval process, it is unusual to receive a substantive response in less than two days. Very specific questions about firefighting sometimes receive a response like, “we will follow guidance from local State Health Departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”