New IAWF board president Kelly Martin

News and opinion about wildland fire

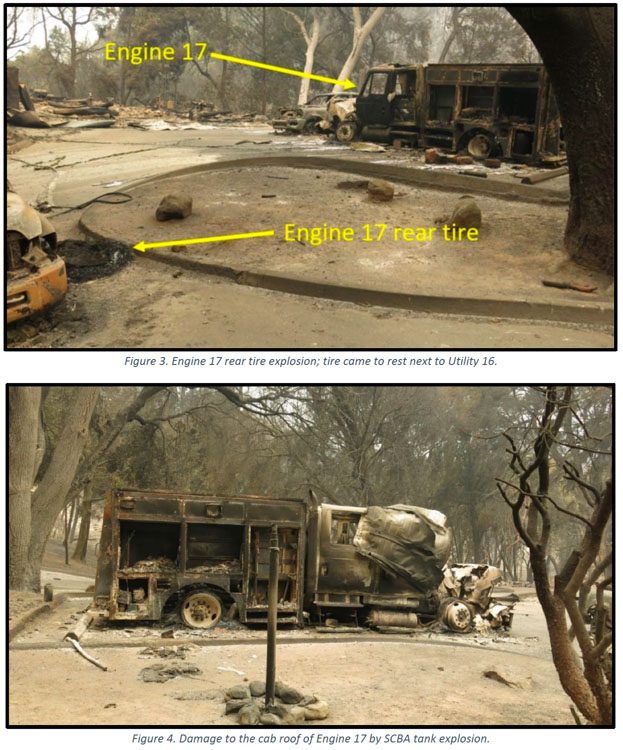

The Nacimiento guard station, two fire engines, several personal vehicles, and two dozers burned — there was one very serious injury

Several “learning reports” have been released by the U.S. Forest Service about the burnover and entrapment one and a half years ago of wildland firefighters at a remote fire station. It occurred on the Dolan Fire on the Los Padres National Forest in Southern California September 8, 2020. Fifteen firefighters deployed into only 13 fire shelters. Four firefighters were injured and three were hospitalized. One had very serious burns.

The Dolan Fire had been burning for weeks but there were about half a dozen other fires in California that were larger, some much larger such as the LNU Lightning Complex, SCU Lightning Complex, CZU August Lightning, and the August Complex.

The Incident Management Team ran a modeling scenario on September 4 which showed that within the next 14 days the probability of the fire reaching the Nacimiento Guard Station was 60 to 80 percent with no delaying tactics. At that time the fire was 3.1 miles away.

The night before the fire reached the station on Nacimiento-Fergusson Road 7 miles from the highway on the California coast, the fire ran for about three miles toward the station, burning 30,000 acres with spot fires three-quarters of a mile ahead. The map below based on infrared data shows the growth in the 26-hour period ending at 2 a.m. on Sept. 8. The fire hit the station between 7 and 8 a.m. on September 8.

When the fixed-wing aircraft mapped the fire five or six hours before the incident, it had burned about 74,000 acres, more than twice the size mapped the previous night. The sensors on the plane detected intense heat on the southern edge of the fire, 0.7 miles north of Nacimiento Station.

(To see all articles on Wildfire Today about the Dolan Fire, click here: https://wildfiretoday.com/tag/dolan-fire/)

The fire personnel at the station during the burnover included two USFS engine crews, two dozers with operators, and the only Division supervisor working the night shift — due to a shortage of personnel. Other overhead at the fire may have been distracted as a newly established Incident Command Post had to be evacuated and relocated as the fire approached in the middle of the night.

Several of those involved at Nacimiento believed there was no way to defend the station even though a hand crew had cleared some vegetation, a hand line had been dug, and there were hose lays around the structures. With that work done and the fact that the station had survived other fires, some of the locals said they could protect the buildings and the personal belongings and vehicles of the fire personnel who lived there.

Below is an aerial photo of the Nacimiento Guard Station taken almost exactly two years before the burnover. It appeared in an article on Wildfire Today about the entrapment published September 11, 2020.

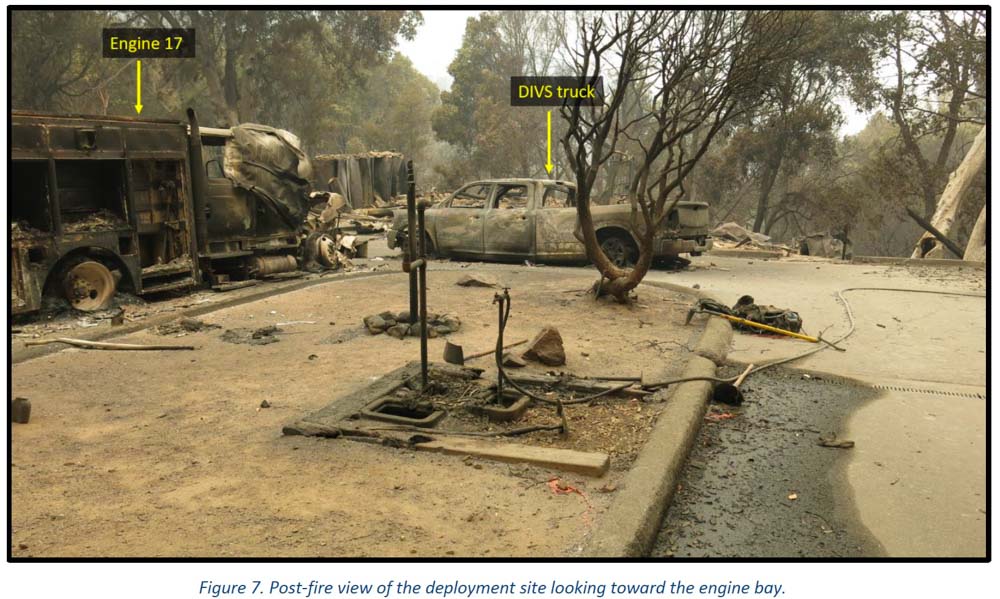

The photo below was taken after the burnover.

This is the first paragraph in the Learning Review — Narrative:

Smoke is billowing out of the barracks and hot embers are raining down all around. Engine 16 is on fire. The engine bay is on fire. Marty can’t get his pack out of the burning engine, which means he can’t get to his fire shelter. He’s just standing there, and Rene can’t get his attention. She has her shelter out, ready to go. She hits him, but he just stands there. She hits him again, but he still just stands there. Marty is not ready to commit to the shelter; he’s thinking about potential dangers from the propane tanks around them, and that more needs to or could be done. Rene hits him again and pulls down on his shirt to get him down to the ground and into the fire shelter. Rene tucks the fire shelter around him and cinches it in tight under his arms and legs. She takes a quick look around and then climbs in under the shelter with him. Eleven other firefighters are deployed around them in the parking lot of the Nacimiento guard station. The heat inside the shelters was stifling. “I could feel the skin tightening on my face. Mucous was coming out of my nose and eyes, hanging off my chin. I felt like all the fluid was being roasted out of me. My throat was so sore I could barely drink my water.” Everyone is asking the same question: “How did we get here?”

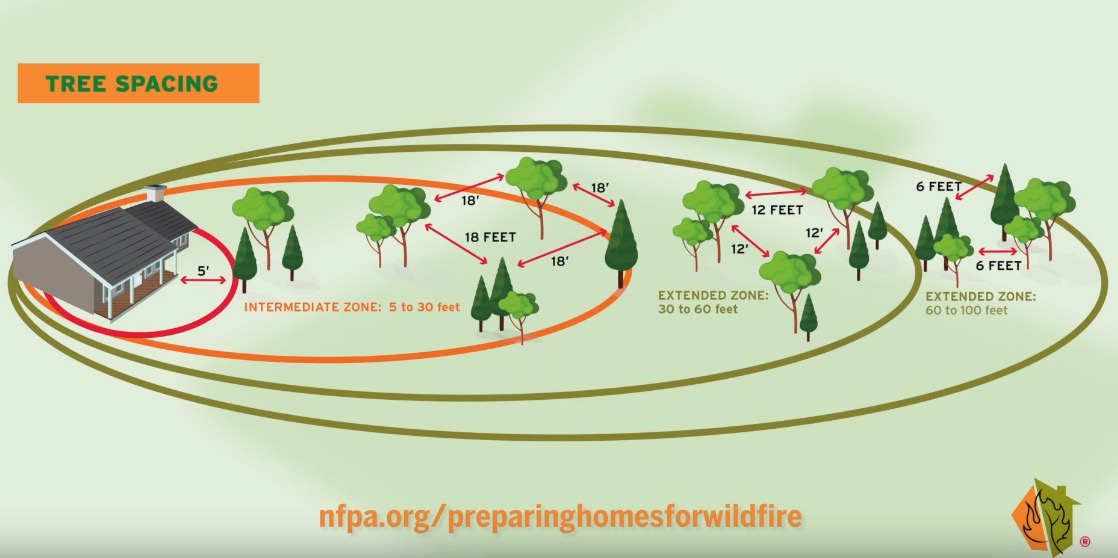

The Organizational Learning Report has a section, Theme 3, pointing out that even though the Forest Service has “preached [to homeowners] FireWise concepts for decades” about how to reduce the chances of their houses burning as a wildfire approaches, too many of the agency’s own structures lack FireWise status. The report says, “If we preach it, we should do it. ”

We asked Kelly Martin for her thoughts about the reports on the Dolan Fire. She is the current president of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters and the retired Chief of Fire and Aviation for Yosemite National Park. She replied by text:

The biggest thing that comes to mind is our over confidence in what we deem ‘defendable’ until the time wedge becomes too small to make safe, proactive decisions. The oppressive personal/social pressure to protect treasured places puts us in an untenable situation to champion the notion, ‘not on my watch’ are we going to lose this place. The protection narrative gets repeated and reinforced by the majority who consider it ‘their home turf’ and unfortunately tend to dismiss many ‘outsiders’ objective perspectives on the situation that might help reduce the deep personal attachment to ‘home turf.’ Having ‘Outsiders’ become part of the decision making process can help enhance rational decision making.

Confirmation bias may have been a factor. The fire station survived previous fires, thus lulling us to previous events rather than fully appreciating the situation we now find ourselves in with excessive fuel buildup.

Also, I think the Wildfire Decision Support System (WFDSS) process and further high level local management and Incident Management Team analysis should have spotted this mindset trap early on.

The disaster at the Dolan Fire is yet another example where knowing the real-time location of the fire may have made a difference. The Captain who ran the station and some other locals believed that they needed to protect the facility and insisted that they COULD. Others thought differently but were not assertive enough or didn’t have the authority to override that decision. They knew the fire was approaching. But would things have turned out differently with others who didn’t have emotional attachments to the buildings? Or who had real-time intelligence, and could “see” the locations of all resources as well as the entire fire — the very rapid rate of spread, the spot fires ¾ mile ahead, and the intensity? What if the Operations Section Chief, Branch Director, primary Safety Officer, or the Incident Commander had access to real-time video from a drone circling over the fire? Any one of those might have ordered the withdrawal of the engines, dozers, and 15 firefighters hours before they came close to death. They might have said, “Forget the damn structures. Think about the humans. Consider the physical and mental trauma those humans could suffer, perhaps for years.”

The decision to stay or go, in addition to human safety, should have also considered the dollar value of the personal belongings and vehicles of the employees who lived at Nacimiento. They were not evacuated days earlier even though the station was in a mandatory evacuation area. They trusted the Incident Management Team, the Forest overhead, and the Captains. How much will it cost those firefighters, on their meager salaries, to replace their personal vehicles and belongings? Then there is the cost to taxpayers of two engines, two dozers, and at least one pickup truck.

The technology has existed for years to provide real-time video of fires 24 hours a day. The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act required that by September 12, 2019 the five federal land management agencies “develop consistent protocols and plans for the use on wildland fires of unmanned aircraft system technologies, including for the development of real-time maps of the location of wildland fires.”

While this technology has been demonstrated and used sparingly, such as the FIRIS program, real-time mapping is far from being used routinely.

The Dingell Act also mandated that the five federal land management agencies “jointly develop and operate a tracking system to remotely locate the positions of fire resources for use by wildland firefighters, including, at a minimum, any fire resources assigned to Federal type 1 wildland fire incident management teams,” due by March 12, 2021.

The Bureau of Land Management has installed hardware for Location Based Services (LBS), which are now operational on more than 700 wildland fire engines, crew transports, and support vehicles. Vehicle position and utilization data are visually displayed via a web-based portal or mobile device application. Ten months after it was required by Congress, the U.S. Forest Service has made very little progress on this mandate.

It is not just the Forest Service with structures that do not all meet FireWise standards. When I was an area Fire Management Officer for the National Park Service, two of the parks for which I was responsible were threatened on different occasions by wildfires. Although the threat was low to moderate, I was able to convince the Park Superintendents that hazard reduction and thinning of the trees was necessary, now. It should have already been done, but seeing smoke in the air made it possible to make fast decisions and to get it accomplished very quickly. Up until then, removing any tree near park headquarters was a tough row to hoe. Neither fire spread into the parks, but the long-delayed and badly needed work got done. And I slept better.

Laura Paskus, a reporter and producer for PBS of New Mexico, interviewed three wildland firefighters for an episode of Our Land: New Mexico’s Environmental Past, Present, and Future. They covered some of the pressing issues faced by wildland firefighters, including health care, benefits, extensive travel, and pay.

Seen in the video are Marcus Cornwell, federal wildland firefighter; Kelly Martin, president of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters; and Jonathon Golden, former wildland firefighter.