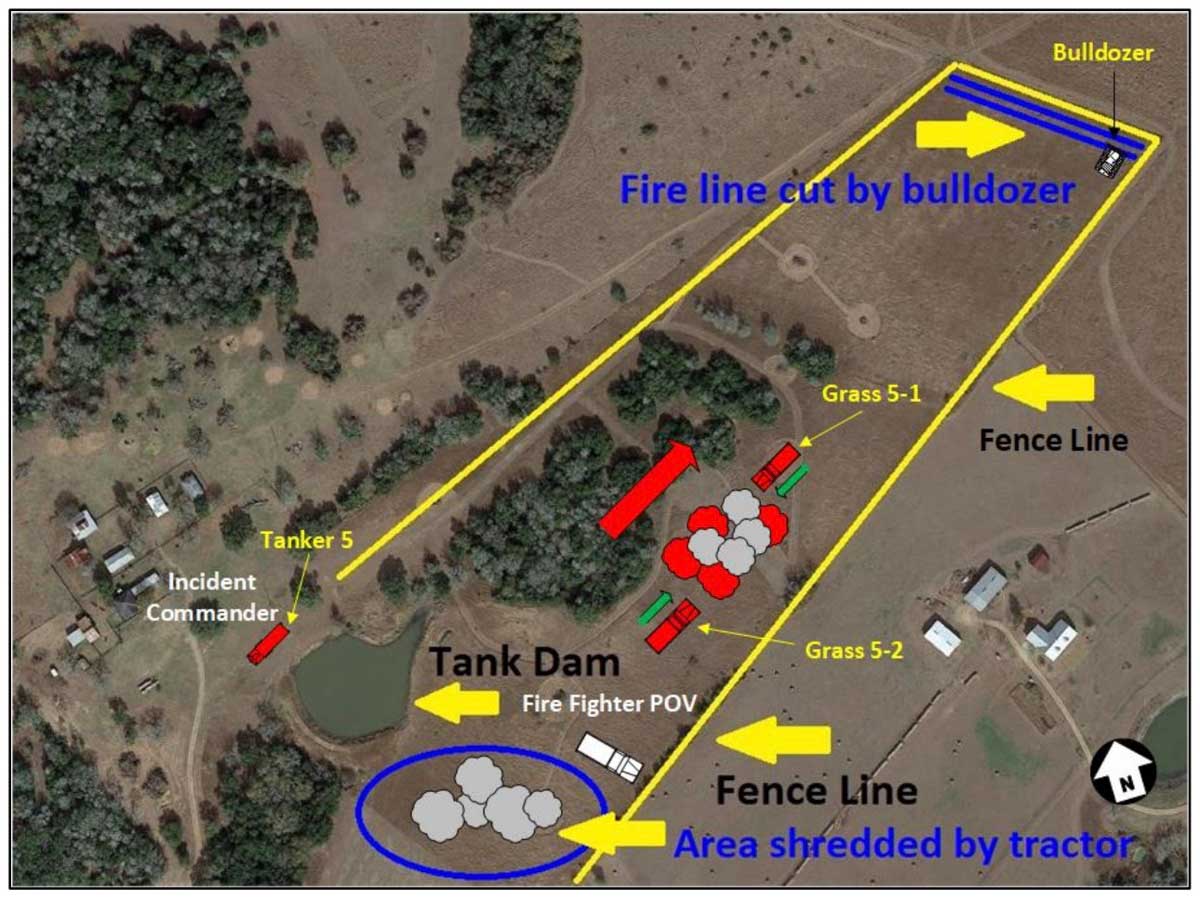

arrows indicate the direction of travel for the brush trucks. The red arrow is the

direction the fire is traveling. The time is approximately 1124 hours. (NIOSH)

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has released a report about a 68-year old firefighter that died from burn injuries while fighting a grass fire in Texas last year.

“Firefighter A” was one of three firefighters on a Brush Truck, Grass 5-1, that was initial attacking a grass fire on March 10, 2018 that was burning in two to three foot high Little Bluestem grass. He was riding on an open side step behind the cab when he fell off and was overrun by the fire. The firefighter was flown to a burn center but passed away March 23, 2018.

Below is an excerpt from the report:

“Grass 5-1 began attacking the fire from the burned “black” area. Grass 5-1 was attempting to extinguish the fire in the tree line and fence line while moving north. A bulldozer was operating north of Grass 5-1. A citizen was operating a private bulldozer independent of the fire department operations. The bulldozer was attempting to cut a fire break in the very northern part of the property ahead of the fire.

“Grass 5-2 arrived on scene at 1121 hours. Another fire fighter from Fire Station 5 had responded in his POV to the scene. He got in the cab of Grass 5-2 at the tank dam. Grass 5-2 went east in the field towards the fence line. The grass fire was near the POV owned by Fire Fighter “B” on Grass 5-1. Grass 5-2 extinguished the fire around the POV and moved north towards Grass 5-1.

“Grass 5-1 reached the head of the fire and lost sight of the bulldozer. The driver/operator of Grass 5-1 attempted to turn around and the wind shifted, causing the smoke to obscure his vision. The driver/operator inadvertently turned into the unburned grass. The driver/operator described the grass as two to three feet tall. The time was approximately 1124 hours.

“The wind shift caused the fire to head directly toward Grass 5-1. Grass 5-1 Fire Fighter “B” advised the driver/operator to stop because they were dragging the “red line” (booster line). Fire Fighter “A” and Fire Fighter “B” exited the vehicle to retrieve the hoseline. The driver/operator told them to “forget the line” and get back in the truck. Fire Fighter “B” entered the right side (passenger) side step and Fire Fighter “A” got back on Grass 5-1 on the side step behind the driver. Fire Fighter “A” had a portion of the red line over his shoulder. When the driver accelerated to exit the area, Fire Fighter “A” was pulled from the apparatus by the red line that remained on the ground due to the gate not being properly latched. Fire Fighter “B” started pounding on the cab of Grass 5-1 to get the driver/operator to stop the apparatus. Grass 5-1 traveled approximately 35 – 45 feet before the driver/operator stopped the apparatus. The time was approximately 1127 hours.

“When Fire Fighter “A” fell off of Grass 5-1, he fell into a hole about 6 – 12 inches deep and was overrun by the fire. The driver/operator and Fire Fighter “B” found Fire Fighter “A” in the fire and suffering from burns to his face, arms and hands, chest, and legs. They helped Fire Fighter “A” into the cab of Grass 5-1 with assistance from the two fire fighters on Grass 5-2. The driver/operator of Grass 5-1 advised the County Dispatch Center of a “man down”. Once Fire Fighter “A” was in the cab of Grass 5-1, the driver/operator drove Grass 5-1 to the command post, which was located near Tanker 5. Fire Fighter “B” was riding the right step position behind the cab of Grass 5-1. The time was approximately 1129 hours. At 1131 hours, the County Dispatch Center dispatched a county medic unit (Medic 2) to the scene for an injured fire fighter.”

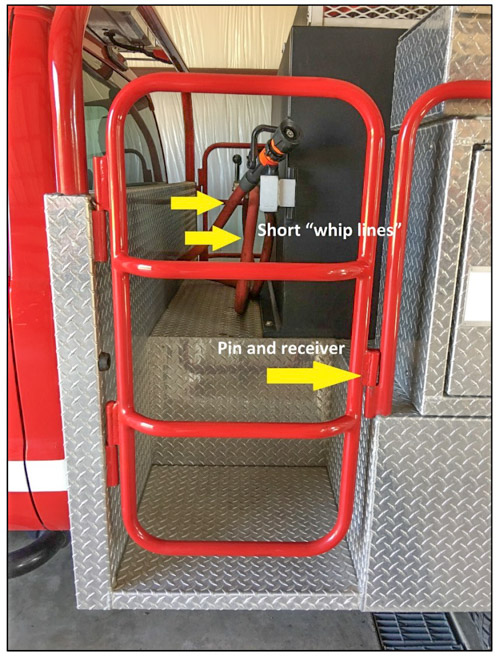

mechanism and the short hoselines on each sided of the apparatus

(NIOSH Photo.)

Instead of wearing the fire resistant brush gear or turnout gear he had been issued, Firefighter A was wearing jeans, a tee shirt, and tennis shoes.

Contributing factors and key recommendations from the report:

Contributing Factors

- Lack of personal protective equipment

- Apparatus design

- Lack of scene size-up

- Lack of situational awareness

- Lack of training for grass/brush fires

- Lack of safety zone and escape route

- Radio communications issues due to incident location

Key Recommendations

- Fire departments should ensure fire fighters who engage in wildland firefighting wear personal protective equipment that meets NFPA 1977, Standard on Protective Clothing and Equipment for Wildland Firefighting

- Fire departments should comply with the requirements of NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Program for members riding on fire apparatus

The report referred to an August 17, 2017 tentative interim amendment to NFPA 1906, Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus, 2016 edition with an effective date of September 4, 2017.

“NFPA 1906 Paragraph 14.1.1 now reads, “Each crew riding position shall be within a fully enclosed personnel area.”

“A.14.1.1 states, “Typically, while engaged in firefighting operations on structural fires, apparatus are positioned in a safe location, and hose is extended as necessary to discharge water or suppressants on the combustible material.” In wildland fire suppression, mobile attack is often utilized in addition to stationary pumping. In mobile attack, sometimes referred to as “pump-and-roll,” water is discharged from the apparatus while the vehicle is in motion. Pump-and-roll operations are inherently more dangerous than stationary pumping because the apparatus and personnel are in close proximity to the fire combined with the additional exposure to hazards caused by a vehicle in motion, often on uneven ground. The personnel and/or apparatus could thus be more easily subject to injury or damage due to accidental impact, rollover, and/or environmental hazards, including burn over.

“To potentially mitigate against the increased risk inherent with pump-and-roll operations, the following alternatives are provided for consideration: (1) Driver and fire fighter(s) are located inside the apparatus in a seated, belted position within the enclosed cab. Water is discharged via a monitor or turret that is controlled from within the apparatus.

(2) Driver and fire fighter(s) are located inside the apparatus in a seated, belted position within the enclosed cab, but water is discharged with a short hose line or hard line out an open cab window.

(3) Driver is located inside the apparatus in a seated, belted position within the enclosed cab with one or more fire fighters seated and belted in the on-board pump-and-roll firefighting position as described in a following section.

(4) Driver is located inside the apparatus in a seated, belted position within the enclosed cab. Firefighter(s) is located outside the cab, walking alongside the apparatus, in clear view of the driver, discharging water with a short hose line.

“Under no circumstances is it ever considered a safe practice to ride standing or seated on the exterior of the apparatus for mobile attack other than seated and belted in an on-board pump-and-roll firefighting position. [2016b].”