There's nothing cool about cancer. Clean it!@paulcombsart #drawnbyfire @fireengineering pic.twitter.com/S92z9d1Qc1

— Paul Combs (@paulcombsart) October 13, 2016

Tag: safety

Stupid people are confident, while the intelligent are doubtful

Here is a blast from the past — an article we wrote May 12, 2010.

That headline is how an introduction to a transcript from a radio program begins on the Australian network, ABC. On the program The Science Show, they explored the conclusions reached by David Dunning and Justin Kruger when they studied people’s perceptions of their own talents. Now known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, it helps explain why moderately skilled people act as experts, and inept politicians get our votes.

We’ll touch on how this relates to wildland fire in a moment, but first here are some excerpts from the radio show transcript.

…And here’s the kicker; across every test, the students at the bottom end of the bell curve held inflated opinions of their own talents, hugely inflated. In one test of logical reasoning, the lowest quartile of students estimated that their skills would put them above more than 60% of their peers when in fact they had beaten out just 12%. To put that misjudgement in perspective, it’s like guessing that this piece of music [music for 5 seconds] lasted nearly half a minute.

Even more surprisingly, the Dunning-Kruger effect leads high achievers to doubt themselves, because on the other end of the bell curve the talented students consistently underestimated their performance. Again to the test of logic; those topping the class felt that they were only just beating out three-quarters of their classmates, whereas in reality they had out-performed almost 90% of them.

The verdict was in; idiots get confident while the smart get modest, an idea that was around long before Dunning and Kruger’s day. Bertrand Russell once said, ‘In the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.’ From his essay ‘The Triumph of Stupidity’, published in 1933.

…

Charles Darwin once said, ‘Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than knowledge,’ and Dunning and Kruger seem to have proven this point. In light of this, it suddenly becomes clear why public debate can be so excruciating. Debates on climate change, the age of the Earth or intelligent design are perfect real-life examples of the Dunning-Kruger effect. It beautifully explains the utter confidence of those who, with no expertise, remain stubborn in their views regardless of overwhelming evidence. It makes you want to shake them by the collar and scream about how stupid they are. But evidence shows that’s not the best strategy.

Have you ever been on a fire and met a Squad Boss, Crew Boss, or Division Supervisor who you knew was not the sharpest tool in the cache, but who was supremely confident in their abilities? They might be the person who just can’t understand why their supervisors have not recognized their huge potential and wonder why they have not been promoted every year.

In some cases, this person may be ineffective but benign. Their screw-ups may be inconvenient or costly but not life-threatening. But if someone on a fire, with power and authority, over-estimates their skill and ability, the consequences can be disastrous.

Some people don’t know what they don’t know. They have no idea or self-awareness about the holes in their knowledge and experience. You may know of a politician or two that can be described this way coughsarahpalincough.

I can think of several fatality and near-miss incidents on wildfires where this was, in my humble opinion, the primary cause of the accident. But it is not politically correct for the writers of the accident reports to spell it out so clearly. One report that came close is the one about last August’s escaped prescribed fire in Yosemite National Park where the the writers used the term “hubris”.

How do we avoid the trap of over-confident people making poor decisions on fires?

- The first step is to be sure that firefighters can proficiently perform the jobs that appear on their red cards.

- Next, be sure that everyone receives an honest performance rating on every fire, at least a verbal one, and preferably a written one for significant fires or assignments.

- Conduct After Action Reviews at the end of shifts or fires.

- And, if you are given an assignment that does not make sense, or causes the hair on the back of your neck to stand up, say something.

- If an individual does this to you repeatedly, have a chat with their supervisor or the Safety Officer. Filing a SAFENET form that does not list names may not be effective.

****

More about the Dunning-Kruger effect.

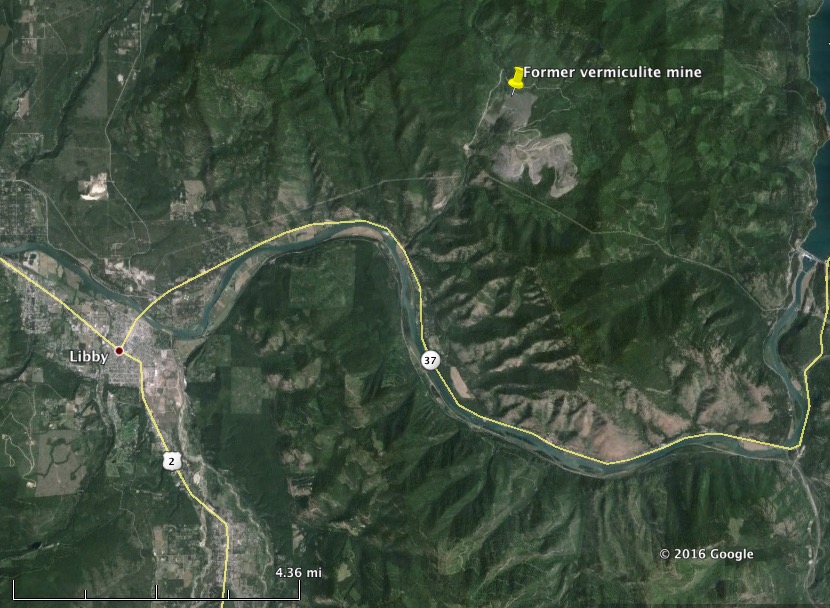

USFS having difficulty hiring firefighters to suppress wildfires in area contaminated with asbestos

The U.S. Forest Service is trying to fill positions on a very specialized 10-person wildland firefighting crew. The mission of the crew would be to suppress wildfires that occur near a mining site at Libby, Montana where vermiculite contaminated with asbestos was extracted by the Zonolite Corporation and later by W.R. Grace from 1919 until the mine closed in 1990. The asbestos became airborne and deposited in the adjacent forest and other areas. Wastes from the mine were used throughout Libby in many public places such as school tracks, public parks, baseball fields, as insulation in public buildings and schools.

The area is now designated by the Environmental Protection Agency as a Superfund Site. The first public health emergency ever declared by the EPA was the Libby asbestos site in 2009. Hundreds of asbestos-related disease cases have been documented in the small community, which covers the towns of Libby and Troy.

Below are excerpts from an article at The Western News:

…As part of a previous agreement, the Forest Service is responsible for fire containment and cleanup in the mine area. Libby District Ranger Nate Gassmann said having a team located in the area is critical to containing the threat of airborne asbestos if that case were to happen.

“Both agencies understand that importance if the community of Libby and the surrounding area is affected by fire in someway,” Gassmann said. “We do not take this as a light consideration for the Forest Service.

Christina Progess, remedial project manager for Operable Unit 3, known also as the former W.R. Grace mine site, said that the EPA worked hand-in-hand with the Forest Service to develop the action plan, while state agencies like the Department of Environmental Quality and Department of Natural Resources and Conservation took support roles, providing input while the plan was under development. Progess said the plan released on Tuesday has been in the works since spring of 2016.

The team would be composed of Forest Service firefighters, according to the plan, but filling that roster has already proven difficult. According to the memo, Forest Service Fire Managers have discussed firefighting within OU3 with Forest Service firefighters and “most have indicated that they would refuse to work in OU3 due to the presence of (Libby Amphibole asbestos) in forest duff and tree bark.”

Gassmann said while efforts to build the team has been met with hurdles, some support positions have already been filled and the Forest Service may begin looking to outside sources to compose the 10-person squad.

Gassman also said the Forest Service has provided forest fire containment in the mining area before, including two incidences in 2015, although those fires totaled a .75-acre area.

“On average, we receive four fires a year” in the former mine area, Gassman said. “Sometimes you get more, sometimes you don’t.”

Progess said the EPA and Forest Service conducted a test burn earlier this year to determine the exposure levels found in the smoke and ash of a fire in the former mine area. The test burn was a small fire, she said, but the exposure levels were great.

“We had the test burn and had firefighters do some mop up in the area. We found that their exposures were well above the risk target set by the EPA,” she said.

“Exposures were significant and of concern.”

Progess said that if a large forest fire were to tear through the former mine site, the EPA is currently unable to quantify how far or how concentrated the mobilized asbestos would travel through smoke and ash.

“There’s so many variables that would factor into it, from wind to topography to the relative humidity,” she said. “We don’t have any way of understanding what the concentrations would be to residents in Libby but the best way to minimize exposure is to prepare to stop a fire.”

Gassmann said while the primary objective is to keep area residents safe from such asbestos exposure levels, there’s plenty of concern for the safety of the firefighting team, once that crew is assembled.

“We have a requirement to provide health and safety for our fire fighters. That’s above and beyond what you would consider a normal fire fighting activity,” he said.

Safely training the tactical athlete

After reading the Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) about the Rhabdomyolysis (Rhabdo) injury that occurred May 2 in South Dakota on the first day of the fire season after running for more than nine miles before doing uphill sprints, I started thinking about, not so much WHAT happened, but how to prevent similar serious injuries.

After reading the Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) about the Rhabdomyolysis (Rhabdo) injury that occurred May 2 in South Dakota on the first day of the fire season after running for more than nine miles before doing uphill sprints, I started thinking about, not so much WHAT happened, but how to prevent similar serious injuries.

A couple of weeks before the Rhabdo case, on April 19 a wildland firefighter in the Northwest suffered a heat stroke while running on day 2 of their season. The employee was unconscious for several hours and spent four days in the hospital.

Both of these exercise-induced conditions can be life-threatening; 33 percent percent of patients diagnosed with Rhabdo develop a quick onset of kidney failure, and 8% of all cases are fatal.

Heat stroke can also kill, according to Medscape:

When therapy is delayed, the mortality rate may be as high as 80%; however, with early diagnosis and immediate cooling, the mortality rate can be reduced to 10%.

These two very serious incidents in a two week period that occurred at the beginning of the fire season should be a wakeup call for agencies employing wildland firefighters.

I am not a medical or exercise specialist, but neither were any of the four members of the South Dakota Rhabdo FLA team. It was comprised of a District Fire Management Officer, a Natural Resources Specialist, an Assistant Superintendent on a Hotshot crew, and an Assistant Fire Engine Operator.

A person might expect that for an exercise-induced injury that is fatal in eight percent of the cases, a medical expert and an exercise physiologist would be members of the team. The FLA concentrated on recognizing symptoms of Rhabdo, which is good. Firefighters need to be be informed, again, about what to look for. But the necessity of treating the symptoms could be avoided if the condition was prevented in the first place.

Prevention was not addressed in the document, except to mention availability of water. Dehydration isn’t the leading cause of Rhabdo, which is caused by exertion, but it can be a contributing factor.

With two life-threatening medical conditions on firefighting crews in a two-week period that occurred during mandatory exercise on day one and two of training, medical and exercise professionals perhaps could have evaluated what caused the injuries, and suggested how to design and implement a physical fitness program that would lessen the chances of killing firefighters on their first or second day on the job. But the LEARNING opportunity of the FLA was squandered.

The wildland fire agencies are not alone in hiring people off the streets and throwing them into a very physically demanding job. The military does this every day, as do high school athletic programs. There is probably a large body of research that has determined how to turn a person into an athlete without putting their lives in danger.

While the three firefighters and the natural resources specialist I’m sure meant well and did the best they could to write the FLA within the limits of their training and experience, the firefighting agencies need to get serious about a professional level exercise training program. After all, they are employing TACTICAL ATHLETES.

This issue is serious enough that the NWCG (since there is no National Wildland Firefighting Agency) should hire an exercise physiologist who can design, implement, and monitor a program for turning people off the street into tactical firefighting athletes.

Facilitated Learning Analysis for May 2 Rhabdo injury

33% of patients diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis develop a quick onset of kidney failure, and 8% of all cases are fatal.

The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center has released a Facilitated Learning Analysis for the Rhabdomyolysis injury that occurred May 2, 2016. It does not specify that it was the case that occurred on the Black Hills National Forest, but many of the facts in the document point to it being the same incident.

The short version of what preceded the injury is that on the morning of the first day of the seasonal firefighters reporting for duty this fire season, the crew was directed to complete an 8.8 mile run which they did in 96 minutes. Approximately 1/2 mile into the run one crewmember dropped out and was evaluated by a squad boss and an EMT. The crewmember and the EMT returned to the base. This was not the person later diagnosed with Rhabdo.

After the 8.8 mile run the crew jogged another 3/4 mile to a location where they ran uphill sprints and a “loop run”. From the report, after the 8.8 mile run:

Upon return to station, the remainder of the crew reconfigured and lined-out in “tool-order” to continue PT. It was noted that during this brief lull in activity, the employee who would eventually be diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis made the comment “It’d be nice to have some water…”, to which another within ear-shot replied “yeah… I know”. The “long, slow run” was followed by three rounds of relatively short uphill sprints interrupted by a “loop-run” within sight of the hot-shot base. This event lasted roughly forty-five minutes.

Although dehydration isn’t the leading cause of Rhabdomyolysis, which is a condition caused by exertion, it can be a contributing factor.

The crewmember did not inform the supervisors that he was having discomfort and cramping, but about an hour after the work day ended he drove himself 41 miles to seek treatment at a medical facility.

At 0745 on the [next] morning of May 3rd, the hotshot superintendent was notified by the injured employee’s family that he was in the hospital with dehydration and were awaiting additional test results. He was subsequently diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis.

The FLA points out, and this should not be news to wildland firefighters, that Rhabdo and compartment syndrome are extremely rare and difficult for a physician to diagnose. Therefore it is imperative that wildland firefighters familiarize themselves with what can cause the condition and how to recognize the symptoms.

Not all past cases of rhabdo in wildland firefighters were correctly diagnosed during initial care. Heat illness and dehydration share common signs/symptoms and can lead to a missed diagnosis for rhabdo. In addition, rhabdomyolysis is a very rare occurrence in the general population. Many physicians will go their entire careers without seeing a single case of rhabdomyolysis. Since early detection and treatment can greatly reduce the severity and recovery time, it is important that medical providers understand and test for rhabdo.

If you are a wildland firefighter, and especially if you are a supervisor, read the entire report, make copies of the Handout for Medical Providers, and if someone exhibits the symptoms and needs treatment, accompany them to the medical facility and diplomatically talk to the physician about the possibility of Rhabdo while giving them a copy of the Handout.

In another injury involving early fire season physical training, on April 19 a wildland firefighter suffered a heat stroke on day 2 of their season. The employee was unconscious for several hours and spent four days in the hospital.

Another serious injury during PT at beginning of fire season

The firefighter spent four days in the hospital after suffering heat stroke.

Another firefighter has sustained a very serious injury during physical training at the beginning of their fire season. The first one that we are aware of this year occurred on May 2 in South Dakota when on the first day of training the firefighter was diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis.

The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center just released a “72 hour report” from the Pacific Northwest Region about an April 19 heat stroke victim that happened on the second day.

Both of these conditions are extremely serious and in the worst case, can lead to death.

It must be very difficult to develop a perfect exercise regimen for all 20 people on a hand crew. Especially at the beginning of the season when some of the experienced firefighters may have had an ongoing physical fitness program during the off season, and others are brand new, never having held a shovel, and may have spent the winter on a couch.