All suicides are tragic, but when it happens to a young firefighter who had been on the job for less than a year it is especially so. Nicole Hladik was not a wildland firefighter, but could it happen in any fire organization?

From FirefighterCloseCalls.com:

FIREFIGHTER TAKES HER OWN LIFE.

A family is searching for answers after a 27-year-old Hinsdale Firefighter (Illinois) who died by suicide. Firefighter Nicole Hladik was the only female firefighter at the Hinsdale Fire Department and the third in the town’s history. “Nicki was a bright rising star in the fire service, she was beloved by all of us of course and very happy early on,” Brian Kulaga, Hladik’s uncle, said.

But Kulaga said something changed recently.

“Then she traded shifts and suddenly just a lot of negativity and then leading up to today, which was obviously a complete surprise to all of us,” he said. Hladik died by suicide Tuesday and her brother Joseph Hladik said it was a complete shock. “Super active, super fit, a family person, a great friend, she’s my sister but my best friend,” he said. Hladik’s family said it doesn’t make sense. “Our goal is, we just want someone to look into this, it’s not an accusation. It’s just the facts are, how could someone who was so happy and loved what she was doing go from one spectrum to the other end? It just doesn’t make any sense,” Joseph Hladik said.

Newspaper stories about Nicole Hladik shortly after she was hired at the Hinsdale Fire Department:

–The Hinsdalean, October 9, 2019: Village’s Newest Firefighter Is Happy To be “One Of The Gang”

–Chicago Tribune, October 20, 2019: Shout Out: Nicole Hladik of Willowbrook-Hinsdale’s newest Firefighter

Suicide rates among wildland firefighters have been described as “astronomical.

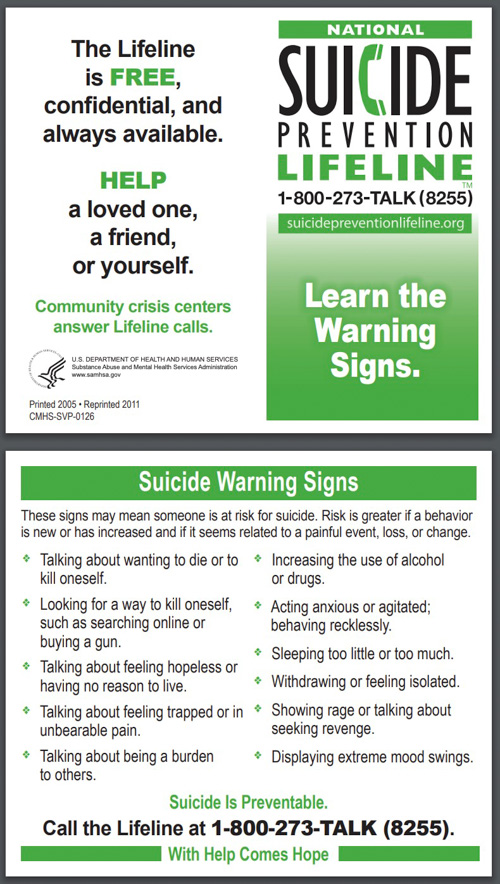

Help is available for those feeling really depressed or suicidal.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255. Online Chat.

- Anonymous assistance from the Wildland Firefighter Foundation: 208-336-2996.

- National Wildland Fire and Aviation Critical Incident Stress Management Website.

- Code Green Campaign, a first responder oriented mental health advocacy organization.

- Would you rather communicate with a counselor by text? If you are feeling really depressed or suicidal, a crisis counselor will TEXT with you. The Crisis Text Line runs a free service. Just text: 741-741