(Originally published at Fire Aviation.)

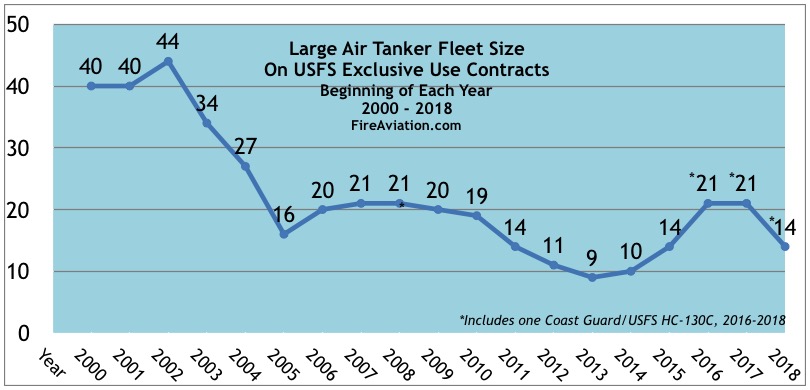

The U.S. federal government has taken steps over the last 16 years that have reduced the number of large air tankers on exclusive use contracts from 44 in 2002 to 13 in 2018. After the wings fell off two air tankers in 2002 killing five crew members, the Forest Service, the agency responsible for managing the program, began cancelling contracts for World War II and eventually Korean War vintage aircraft that had been converted to fight fire.

There was no substantial effort to rebuild the fleet until 11 years later when the USFS began awarding contracts for “next generation” air tankers. A few years after that the last of the 50-year old P2V tankers were retired. Following the half-hearted attempt at rebuilding the program, the total number of tankers on contract rose to 20 in 2016 and 2017, but by 2018 had dropped to 13.

The policies being implemented recently could further reduce the number in the coming years.

In 2016 the USFS awarded a one-year exclusive use contract for two water scoopers, with the option for adding four additional years. In 2017 at the end of the second year the USFS decided to not extend the contract for 2018. But during the 2018 fire season they hired the scoopers on a Call When Needed (CWN) basis. An analysis Fire Aviation completed in February, 2018 found that the average cost to the government for CWN large air tankers is much more than Exclusive Use aircraft that work for an entire fire season. The daily rate is 54 percent higher while the hourly rate is 18 percent higher.

The practice of advertising one-year contracts is now metastasizing, with the solicitation issued by the USFS on December 3 for one-year contracts for “up to five” large air tankers. These potential contracts also have options for four additional years, but could, like the scoopers, be cancelled or not extended at the discretion of the USFS. If the agency decides to award contracts for five aircraft, it would bring the total up to 18.

Earlier this year the USFS shut down the program that was focused on converting seven former U.S. Coast Guard HC-130H aircraft into air tankers. Now they are being moved to the aircraft boneyard in Arizona until the planes can be transferred to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection as required in legislation in August. From 2016 to the summer of 2018 one of the HC-130H’s was used occasionally on fires with a borrowed retardant tank temporarily installed.

Air tankers are very expensive to purchase and retrofit. Most of the jet-powered tankers being used today before being converted were retired from their original mission and are decades old, but two models of scooper or large air tankers can be purchased new. The CL-415 amphibious scooper cost about $37 million in 2014 but Bombardier stopped building them in 2015, and the new owner of the business, Viking, has not resumed manufacturing the aircraft. A new Q400 can be ordered from Bombardier with an external retardant tank for around $34 million.

Most air tanker operators in the United States prefer to buy retired airliners like the BAe-146, DC-10, or variants of the C-130 and convert them to carry and dispense retardant. Retrofitting alone runs into the millions. Few if any vendors can simply write a check to purchase and convert an air tanker, so they have to convince a lender to give them large sums of money usually even before they have a contract with the USFS. With this new one-year contract policy, obtaining those funds could be even more difficult.

Below is an excerpt from the Missoulian:

“They’re only offering a one-year contract,” said Ron Hooper, president of Missoula-based Neptune Aviation. “We can’t go to the bank with a one-year contract to finance airplanes. They just laugh at us.”

Even if a vendor received a guaranteed five-year contract it can be difficult to establish and implement a long-term business plan that would make sense to their banker and the solvency of the company.

The province of Manitoba just awarded a 10-year contract for the management, maintenance, and operation of their fleet of seven water-scooping air tankers (four CL-415s and three CL-215s), supported by three Twin Commander “bird-dog” aircraft.

If the occurrence of wildfires was rapidly declining, reducing the air tanker fleet would make sense. However everyone knows the opposite is happening.

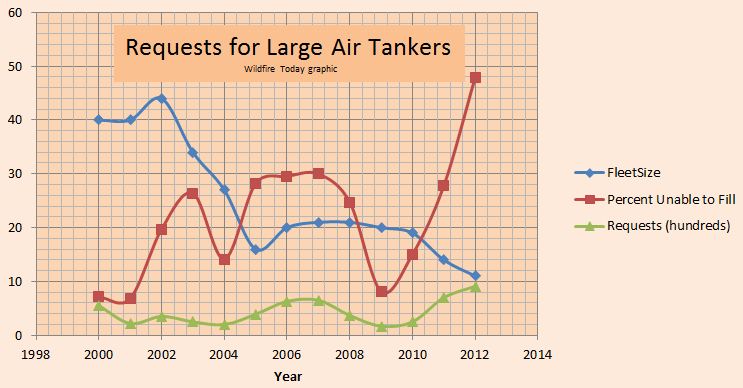

(The two charts below were updated February 2, 2019)

In the late 1980s the average size of a wildfire in the U.S. was 30 acres. That has increased every decade since, bringing the average in the 2010s up to 101 acres.

More acres are burning and the fires are growing much larger while the Administration and Congress reduces the capability of the federal agencies to fight fires.

For the last several years Congress has appropriated the same amount of funds for the U.S. Forest Service, for example. But meanwhile, it costs more to pay for wages, fire trucks, office expenses, travel, and more expensive but safer more reliable air tankers. This leaves less money for everything including vegetation management, prescribed burning, fire prevention, salaries, and firefighting aircraft.

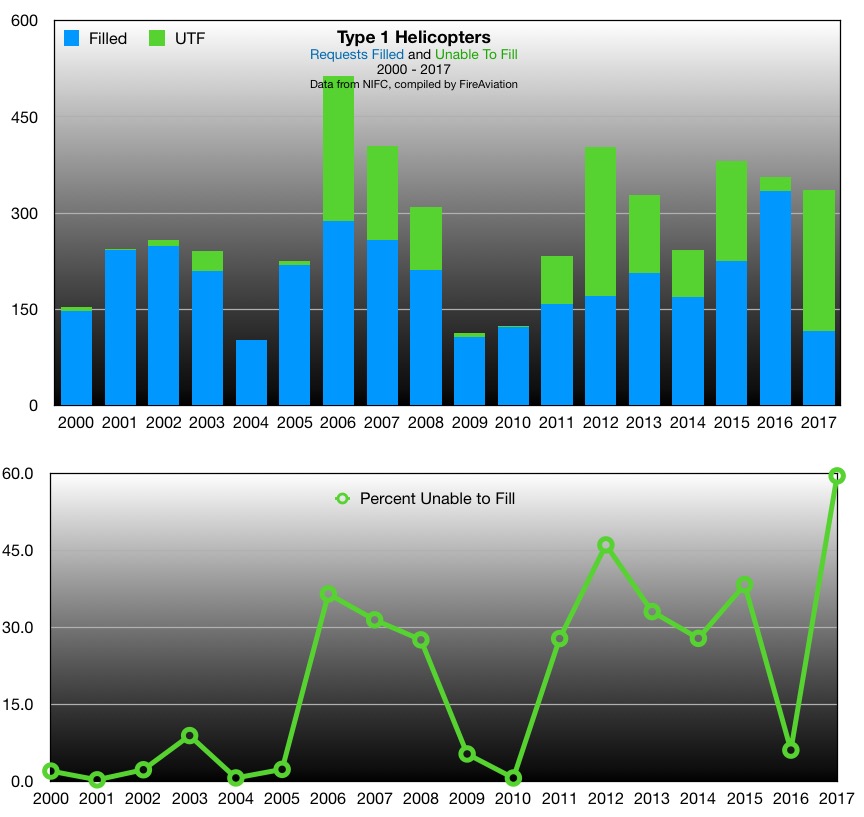

In addition to the reduction in air tankers, the largest and most efficient helicopters, Type 1’s such as the Air Crane, were cut two years ago by 18 percent, from 34 to 28.

In 2017 the number of requests for Type 1 helicopters on fires was close to average, but the number of orders that were Unable To be Filled (UTF) was almost double the number of filled orders. In 2017, 60 percent of the requests were not filled — 220 of the 370 that were needed. That is by far the highest percentage of UTFs in the last 18 years. The second highest was 46 percent in 2012.

Aircraft can’t put out fires, but under ideal conditions they can slow the spread of a fire enough to allow firefighters on the ground to move in and put them out.

It might be easy to blame the USFS for the cutbacks in fire suppression capability, but a person in the agency’s Washington headquarters who prefers to not have their name mentioned said it is a result of a shortage of funds appropriated by Congress. The Administration’s request for firefighting in the FY 2019 budget calls for 18 large air tankers and intends to maintain the 18 percent reduction in Type 1 helicopters, keeping that number at only 28 for the third year in a row.

What can be done?

These one-year firefighting aircraft contracts need to be converted to 10-year contracts, and the number of Type 1 helicopters must be restored to at least the 34 we had for years.

In addition to aircraft, the federal agencies need to have much more funding for activities that can prevent fires from starting and also keep them from turning into megafires that threaten lives, communities, and private land. More prescribed burning and other fuel treatments are absolutely necessary.

The only way this will happen is if the President and Congress realize the urgency and pass and sign the legislation. The longer we put this off the worse the situation will become as the effects of climate change become even more profound.