In another thread there was a discussion about the Yarnell Hill Fire and the fact that when the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots were killed there was only one aerial supervision aircraft over a very complex fire environment instead of two. Until recently it was more common to have both an Air Tactical Group Supervisor (ATGS) and a Lead Plane or Airtanker Coordinator over a fire that had advanced beyond initial attack.

The ATGS orbits the fire and coordinates, assigns, and evaluates the use of aerial resources, both helicopters and fixed wing. The Lead Plane directly supervises the air tankers, usually flying low and sometimes physically preceding the air tankers before they drop the retardant.

But now we sometimes see those two roles combined into one aircraft, called an Aerial Supervision Module. It can save money, but there is debate about how appropriate it is for a complex fire situation.

One of the recommendations in the first report issued about the fire, by the Arizona State Forestry Division last summer, was for the the State of Arizona to “request that the NWCG develop guidance to identify at what point is it necessary to separate the ASM and Air Attack roles to carry out required responsibilities for each platform”. Other documents released by the state of Arizona last week revealed that members of the Blue Ridge Hotshots said that they witnessed “a near miss” with aircraft, who they described as sounding “overwhelmed” adding that “the air show seemed troublesome.”

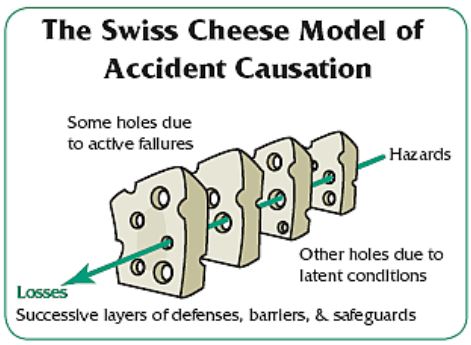

The aerial supervision on the Yarnell Hill Fire was only one element, or one slice of James T. Reason’s Swiss Cheese model of accident causation, which is defined in Wikipedia:

In the Swiss Cheese model, an organization’s defenses against failure are modeled as a series of barriers, represented as slices of cheese. The holes in the slices represent weaknesses in individual parts of the system and are continually varying in size and position across the slices. The system produces failures when a hole in each slice momentarily aligns, permitting (in Reason’s words) “a trajectory of accident opportunity”, so that a hazard passes through holes in all of the slices, leading to a failure.

Having only one aerial supervision platform on a very complex fire gives you one slice with some holes. Below we list 18 other holes in the Swiss cheese.

Another slice would be supervision of ground personnel. The holes in that slice were:

Another slice would be supervision of ground personnel. The holes in that slice were:

- Transitioning that morning from a group of firefighters to only a partial Incident Management Team (all transitions can be tough, but when done hurriedly and to only part of a team, it can be dangerous);

- Removing Supt. Marsh from the Hotshot crew and making him Division Supervisor. (A reporter who has seen the recently released documents told me that Marsh did not know he would be Div. Sup. until he got out on the fire line that day);

- No Safety Officer;

- No Division Supervisors arriving with the IMTeam;

- No Division Supervisor on the Division adjacent to the accident;

- An Incident Commander that took over the fire about six hours before the accident;

- Decision-making was poor, such as failure to designate division breaks, or decide on and communicate a firefighting strategy likely to be successful.

- Somebody, either Marsh, a Structure Protection Group Supervisor, or an Operations Section Chief (or all of the above), decided for the Granite Mountain Hotshots to leave the safe previously burned black area and walk through unburned brush, where they were entrapped by the fire and killed.

Holes in the planning slice were:

- No maps given to firefighters that day;

- No Incident Action Plan that day or the two previous days;

- There was a poor briefing that morning;

- Marsh did not attend the briefing because it was given in mid-morning after he and his crew departed the Incident Command Post and headed to their assignment (Marsh did receive some briefing info that morning).

- There was no complexity analysis completed on day one or day two (the accident occurred on day three of the fire, June 30.) It was completed three hours before the accident.

- The number of firefighting resources working on the fire for the first three days was inadequate to safely implement the strategy of fully suppressing the fire and protecting the structures and the people in the communities.

Holes in the communication slice:

- Incorrect radio programming information was given to firefighters that morning which made radio communication difficult;

- The overhead, such as it was, did not maintain adequate communication with field personnel, which led to inadequate accountability of personnel who were in harms way;

- Marsh and Granite Mountain did not clearly tell the Operations Section Chief where they were and where they were going when they left the secure black en route to the box canyon;

- The ASM had difficulty communicating with Marsh and Granite Mountain as they became entrapped, possibly due to him being “overwhelmed” (as described by the Blue Ridge firefighters).

These slices have 19 holes, and when you place the slices next to each other, all it takes is one more hazard that then passes through holes in all of the slices, leading to an unfortunate outcome. Perhaps if one or more of the holes had been plugged by better management of the fire, there would have been a more favorable result.