(Originally published at 2:46 p.m. MT December 4, 2013; updated at 8:30 p.m., December 4, 2013)

Today the Arizona Division of Occupational Safety and Health (ADOSH) proposed fines totaling $559,000 to be imposed on the Arizona State Forestry Division as a result of the fatalities on the Yarnell Hill Fire near Yarnell, Arizona. Their findings were presented to the Industrial Commission of Arizona during a 1:00 p.m. public meeting in Phoenix. The documents can be found HERE.

On June 30, 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshots were entrapped by rapidly spread flames from a brush fire and were killed. One member of the crew who was in a different location serving as a lookout was not injured.

Two citations were proposed, one “willful serious” with a tine of $545,000, and another that was “serious” with a fine of $14,000.

[UPDATE at 6:46 p.m. MT December 4, 2013; The commission approved the fines. The Arizona State Forestry Division has 15 days to appeal the decision.]

The willful serious citation included the following (paraphrased):

- Failure to furnish a place of employment which was free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm.

- Implementation of suppression strategies that prioritized protection of non-defensible structures and pastureland over firefighter safety.

- The employer knew the suppression was ineffective, and that the wind would push the fire toward non-defensible structures, but firefighters were not promptly removed from exposure to smoke inhalation, burns, and death.

- Thirty-one members of a structure protection group charged with protecting non-defensible structures were exposed to possible smoke inhalation, burns, and death.

- A lookout was exposed to the same dangers.

- Approximately 30 firefighters working on an indirect fireline in Division Z were exposed to the same dangers.

- The Granite Mountain Hotshots continued with suppression activities until 1642 hours on June 30 when they were entrapped by a rapidly progressing wind driven wildland fire.

The serious citation, totaling $14,000:

- The employer failed to implement appropriate fire suppression plans in a timely fashion during a life-threatening transition between initial attack and extended attack.

- When the fire escaped initial attack none of the following analysis procedures were implemented: Incident Complexity Analysis, Escaped Fire Situational Analysis, Wildland Fire Situation Analysis, Wildland Fire Decision Support System, or Operational Needs Assessment.

- On June 29 an Incident Action Plan was not completed for the next operational period prior to transitioning to a more complex management team.

- The positions of Safety Officer and Planning Section Chief were not filled on June 30.

- On June 30 the Division Z Supervisor (adjacent to the Granite Mountain Hotshots’ Division) departed from his assigned position which left Division Z without supervision during ongoing fire suppression operations.

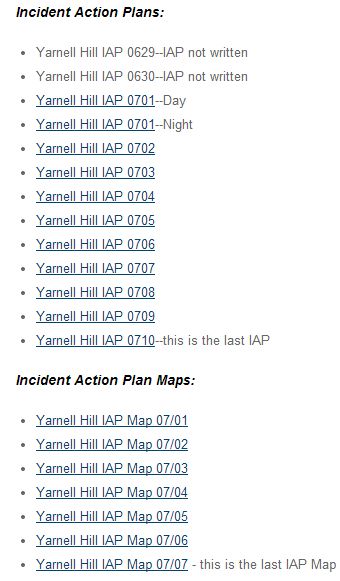

Today, in addition to the citation information, the following documents were released by the Industrial Commission of Arizona:

- Incident narrative and timeline.

- Maps, photos, and diagrams.

- The “Entrapment and Burnover Investigation” report prepared by Wildland Fire Associates.

We will add to this article later with more details about the investigation report, but below are the conclusions reached by Wildland Fire Associates, the consultants hired by the Arizona Division of Occupational Safety and Health:

- Fire behavior was extreme and exacerbated by the outflow boundary associated with the thunderstorm. The Yarnell Hill Fire continually exceeded the expectations of fire and incident managers, as well as the firefighters.

- Arizona State Forestry Division failed to implement their own extended attack guidelines and procedures including an extended attack safety checklist and wildland fire decision support system with a complexity analysis.

- The incident management decision process failed to recognize that the available resources and chosen administrative strategy of full suppression and associated operational tactics could not succeed. This also remained the case when the strategy changed from full suppression to a combination of point protection and full suppression.

- Risk management weighs the risk associated with success against the probability and severity of failure. ASFD failed to adequately update their risk assessment when the fire escaped initial attack leading to the failure of their strategies and tactics that resulted in a life-threatening event.

****

UPDATE at 8:30 p.m. MT, December 4, 2013

We just finished reading the “Inspection Narrative” compiled by AZ OSHA, and the “Granite Mountain IHC Entrapment and Burnover Investigation” report written by Wildland Fire Associates (WFA).

The Inspection Narrative

We noticed a couple of interesting tidbits in the Inspection Narrative that we don’t remember being pointed out in the previous Serious Accident Investigation Team report which was released on September 28.

One was found on page 18. At approximately 1545 hours, one of the the Type 2 Operations Section Chiefs called the Granite Mountain Hotshots and asked if they could spare resources to assist in Yarnell. Either Marsh or GMIHC Captain Steed responded that they were committed to the black and he should contact the Blue Ridge Hotshots.

While the GMIHC said they were not available for the change in assignment, the request from the Ops Chief informed them that they were needed in Yarnell. This may have influenced their decision to move toward the ranch, perhaps with the ultimate goal of assisting in the town. We could not find a mention of this in the WFA report.

One other item in the Narrative (on page 17) we noticed was a disagreement and/or confusion about the break between Divisions A and Z. The Division Z Supervisor didn’t arrive on the fire line until 1 p.m. on June 30. I in addition to the Division break fiasco, he was not clear at all about what tactics in the area could be successful. He left the fire line to head to the Incident Command Post and did not return. Parts of this were also mentioned in the WFA report. The problem with filling the Division Z position was mentioned in the citation.

Below are some quotes from the WFA report:

P. 15: At 1558, ATGS abruptly leaves the fire and goes to Deer Valley. He turned air tactical operations over to ASM2 who was busy dealing with lead plane duties at the time. ASM2 got a very brief update from ATGS that did not include division breaks locations and the location of the on-the-ground firefighters. ASM2 had been ordered as a lead plane because ATGS functions were covered.

Continue reading “State analysis of Yarnell Hill Fire fatalities proposes $559,000 fine for Arizona State Forestry Division”