A conference in Glenwood Springs, Colorado on Wednesday and Thursday of this week explored a topic that does not make the news very often. It was titled The True Cost of Wildfire.

Usually the costs we hear associated with wildfires are what firefighters run up during the suppression phase. The National Incident Management Situation Report provides those daily for most ongoing large fires.

But other costs may be many times that of just suppression, and can include structures burned, crops and pastures ruined, economic losses from decreased tourism, medical treatment for the effects of smoke, salaries of law enforcement and highway maintenance personnel, counseling for post-traumatic stress disorder, costs incurred by evacuees, infrastructure shutdowns, rehab of denuded slopes, flood and debris flow prevention, and repairing damage to reservoirs filled with silt.

And of course we can’t put a monetary value on the lives that are lost in wildfires. In Colorado alone, fires since 2000 have killed 8 residents and 12 firefighters.

The total cost of a wildfire can be mitigated by fire-adaptive communities, hazard fuel mitigation, fire prevention campaigns, and prompt and aggressive initial attack of new fires with overwhelming force by ground and air resources. Investments in these areas can save large sums of money. And, it can save lives, something we don’t hear about very often when it comes to wildfire prevention and mitigation; or spending money on adequate fire suppression resources.

Below are some excerpts from a report on the conference that appeared in the Grand Junction Sentinel:

[Fire ecologist Robert] Gray said the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire in New Mexico ended up having a total estimated cost of $906 million, of which suppression accounted for only 3 percent.

Creede Mayor Eric Grossman said the [West Fork Complex] in the vicinity of that town last summer didn’t damage one structure other than a pumphouse. But the damage to its tourism-based economy was immense.

“We’re a three-, four-month (seasonal tourism) economy and once that fire started everybody left, and rightfully so, but the problem was they didn’t come back,” he said.

A lot of the consequences can play out over years or even decades, Gray said.

He cited a damaging wildfire in Slave Lake, in Alberta, Canada, where post-traumatic stress disorder in children didn’t surface until a year afterward. Yet thanks to the damage to homes from the fire there were fewer medical professionals still available in the town to treat them.

“You’re dealing with a grieving process” in the case of landowners who have lost homes, said Carol Ekarius, who as executive director of the Coalition for the Upper South Platte has dealt with watershed and other issues in the wake of the 2002 Hayman Fire and other Front Range fires.

The Hayman Fire was well over 100,000 acres in size and Ekarius has estimated its total costs at more than $2,000 an acre. That’s partly due to denuded slopes that were vulnerable to flooding, led to silt getting in reservoirs and required rehabilitation work.

“With big fires always come big floods and big debris flows,” Ekarius said.

Gray said measures such as mitigating fire danger through more forest thinning can reduce the risks. The 2013 Rim Fire in California caused $1.8 billion in environmental and property damage, or $7,800 an acre, he said.

“We can do an awful lot of treatment at $7,800 an acre and actually save money,” he said.

Bill Hahnenberg, who has served as incident commander on several fires, said many destructive fires are human-caused because humans live in the wildland-urban interface.

“That’s why I think we should maybe pay more attention to fire prevention,” he said.

Just how large the potential consequences of fire can be was demonstrated in Glenwood Springs’ Coal Seam Fire. In that case the incident commander was close to evacuating the entire town, Hahnenberg said.

“How would that play (out)?” he said. “I’m not just picking on Glenwood, it’s a question for many communities. How would you do that?”

He suggested it’s a scenario communities would do well to prepare for in advance.

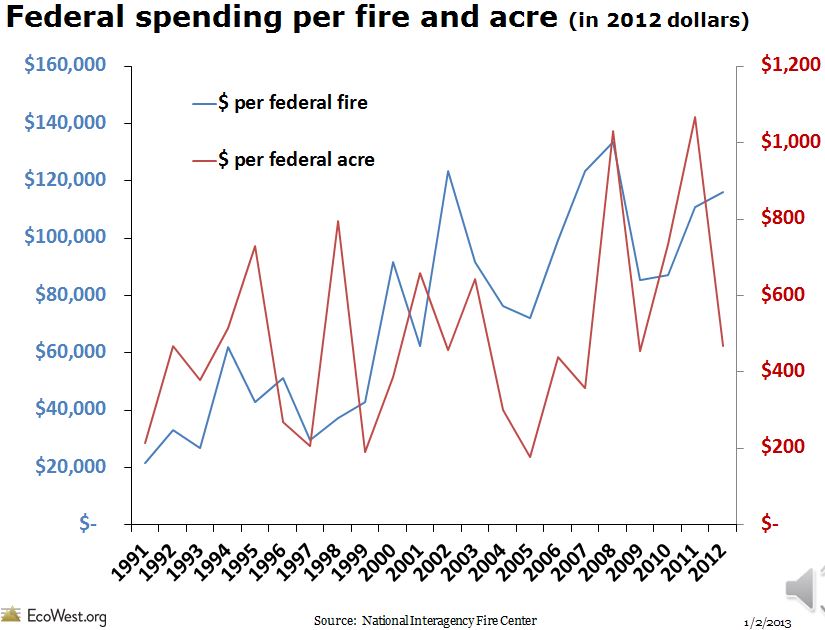

The chart below from EcoWest.org shows that federal spending per wildfire has exceeded $100,000 on an annual basis several times since 2002. Since 2008 the cost per acre has varied between $500 and $1,000. These numbers do not include most of the other associated costs we listed above. (click on the chart to see a larger version)

I have to disagree with saw4fire.

By and large, federal lands do quite well without any management, it’s called nature. The problem is us. We put out fires for the past 100 or so years, build our houses in forested areas (yes, even mine), recreate carelessly, alter the landscape, and generally ignore science and nature.

We all need to share in the costs. State and local governments that allow and encourage development in high hazard areas, insurance company’s that don’t charge according to the risk, property owners that expect something for nothing, and yes, even the Feds need to share this burden.

The real issue that I see with the Feds is their lack of cooperation with local governments. In a recent forest health/mitigation project in my area, the USFS jumped through all of the correct hoops (public meetings, comment periods, etc) then promptly ignored it all and did exactly what their first plan said. Private owners, the county, and state had all done work in the area (and continue to), but there is functionally no coordination with the major work being done by the USFS.

Have to agree with saw4fire…..

Goes for BOTH Congress and the land management agencies….

Until you both realize the word SUSTAINABILITY for the future, then we can start talking intelligently about funding sources and the future of fire…….that includes climate change!

Talk is cheap, making policy to satisfy individual agencies is just an exercise in justification of agency self interest and self preservation, we all got that and it is understandable. But why does one suppose there is such lack of trust in all Guv operations?

Take care of what you own before you lecture the public and make policy on the fly and on the backs of everyone else

That includes both parties, Congress, and the land management agencies……if you can not take care of what you own already, give it to some one else

A lot of folks here chirp about the military and its waste, and that it on them and Congress also and those issues on the CFR’s that regulate how equipment ( after war) and how it is destroyed and sent onto Foreign Military Sales, etc

The land management agencies and their managers probably best learn to be real stewards of the land and get out and mange the land rather than the last 20 + years of “four wall forestry” and hanging out behind technology and social media and we can all see how that has been applied in the true world of forest management and fuels reduction!!!

One of the biggest issues is that Congress funded the purchase of vast federal lands, primarily in the west. Buying it was easy. You have to maintain what you own, but Congress does not want to pay for that. They need to pay for significant thinning, but they actually pay for a tiny, tiny fraction of what is needed.

Here’s a study updated in 2010 for those who want more information on the cost of wildfires.

http://www.blm.gov/or/districts/roseburg/plans/collab_forestry/files/TrueCostOfWilfire.pdf

Bean,

Thanks for the link. It shows that data can be manipulated any way the analyst wants…

To me within the bureaucracy, I see it as just another series of regurgitated “talking points” said over and over again until they are blindly repeated as “facts”.

IMHO

It is widely known and understood that smaller fires have a larger cost per acre. It is simple mathematics of numbers of resources assigned vs. the number of acres burned.

Often missing in the “equation” are the values at risk and their actual cost values.

Much like wars the follow up costs can exceed the initial costs. A single claim for damages or lawsuit can make what appears to be a low cost fire very, very expensive.

Fixing the dispatch system and an aggressive inital attack would drive down the cost per acre.