Of the 22 research proposals funded by the Joint Fire Science Program in June, 16 of them were various ways of studying vegetation. At the time we wrote, “It would be refreshing to see some funds put toward projects that would enhance the science, safety, and effectiveness of firefighting.”

A recently completed study is directed toward the firefighters on the ground. The U.S. Forest Service has paid to have researchers study the feasibility of using LiDAR and computers to determine the most efficient and quickest escape routes if firefighters have to withdraw while attacking a wildfire. The LiDAR helped researchers evaluate how landscape conditions, such as slope, vegetation density, and ground surface roughness affect travel rates.

I have a feeling that there will have to be significant advances in portable handheld technology before fire crews in remote areas can take advantage of this type of data. However, who knows, maybe in 10, 20, 30, or 40 years grunts on the ground will have access to sophisticated tools that we can’t even imagine today. They might just speak into a lapel pin to ask for the best escape route, and an augmented reality head-up display or an orbiting drone with a visible laser will designate the path.

Even though the research was paid for by United States taxpayers through the U.S. Forest Service, those same taxpayers will be charged a second time if they want to see the full results of their investment. The fee is $25 to get a copy of the .pdf. It may be available months or years down the road at no additional cost.

The title of the paper is, A LiDAR-based analysis of the effects of slope, vegetation density, and ground surface roughness on travel rates for wildland firefighter escape route mapping.

A year ago the same group of researchers studied how to find and evaluate safety zones in a paper titled, Safe separation distance score: a new metric for evaluating wildland firefighter safety zones using lidar. This research IS accessible to taxpayers without paying a second time.

The recent paper about escape routes was written by Michael J. Campbell, Philip E. Dennison, and Bret W. Butler. Here is a summary of some of their findings.

Every year, tens of thousands of wildland firefighters risk their lives to save timber, forests and property from destruction. Before battling the flames, they identify areas to where they can retreat, and designate the best escape routes to get from the fire line to these safety zones. Currently, firefighters make these decisions on the ground, using expert knowledge of fire behavior and assessing their ability to traverse a landscape.

Now, a University of Utah-led study has developed a mapping tool that could one day help fire crews make crucial safety decisions with an eagle’s eye view.

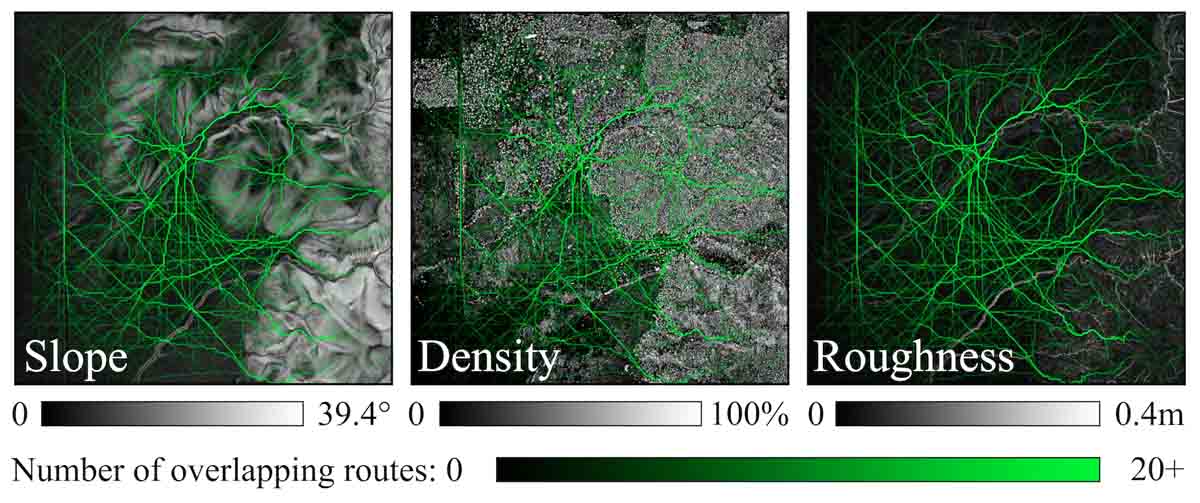

The new study is the first attempt to map escape routes for wildland firefighters from an aerial perspective. The researchers used Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology to analyze the terrain slope, ground surface roughness and vegetation density of a fire-prone region in central Utah, and assessed how each landscape condition impeded a person’s ability to travel.

“Firefighters have a great sense for interactions between fire and landscape conditions. We hope to offer to them an extra tool using information collected on a broad scale,” says lead author Michael Campbell, doctoral candidate in the U’s Department of Geography.

“Firefighters have a great sense for interactions between fire and landscape conditions. We hope to offer to them an extra tool using information collected on a broad scale,” says lead author Michael Campbell, doctoral candidate in the U’s Department of Geography.

Department of Geography professor and co-author, Philip Dennison, adds, “Finding the fastest way to get to a safety zone can be made a lot more difficult by factors like steep terrain, dense brush, and poor visibility due to smoke. This new technology is one of the ways we can provide an extra margin of safety for firefighters.”

The findings were published online on September 26, 2017, in the International Journal of Wildland Fire.

Mapping escape routes

Firefighters identify escape routes by assessing the landscape on the ground. The three conditions that determine how efficiently a firefighter can move through an area are terrain steepness, or slope, vegetation density, especially of plants in the understory and ground surface roughness, such as a boulder field or a well-maintained dirt road.

The study used a combination of LiDAR, geographic information systems, and human volunteers to examine how landscape conditions impact a person’s ability to travel within Levan Wildland Management Area in the foothills of Utah’s Wasatch Mountains.

The volunteers timed themselves walking along 22 paths that the researchers designed to capture a variety of slopes, ground surface roughness and vegetation densities. The researchers compared these travel times to LiDAR-derived estimates of the three landscape conditions along the transects, and extracted their effects on travel rates.

The analysis revealed that the fastest travel rates with respect to slope are slightly downhill, and going steeper uphill or downhill reduces travel speed on average. As vegetation density increases, travel rate decrease and as ground surface roughness increases, travel rates also decline.

“A lot of it is intuitive; if you’re walking through dense vegetation, you’re going to move more slowly than you would through a field of grass. But we found that no-one had quantified just how much vegetation density or surface roughness can slow you down,” says Campbell.

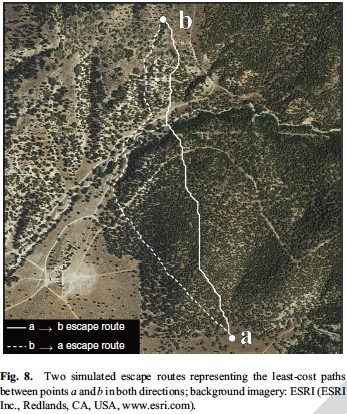

After assessing travel impedance, Campbell ran thousands of simulations evaluating potential escape routes within the study area. He chose random starting points representing a crew location, and random end points representing a safety zone. By plugging the effect of slope, ground surface roughness and vegetation density on travel rates into a route-finding algorithm, he successfully identified the most efficient routes.

Quantifying landscapes from the sky

Currently, firefighters base all of their decisions on ground-level information using fire safety protocols, such as the Incident Response Pocket Guide. The guidelines recommend avoiding steep slopes, dense vegetation, and rough ground surfaces when designating an escape route.

“It’s built into the safety protocol, but there are no numbers behind it. What is steep? Is it steep uphill? Downhill? What is dense vegetation?” asks Campbell. “Using LIDAR information, we were able to turn it from these subjective judgement calls into something more robust and quantitative.”

LiDAR is unique in that it has the ability to map both understory vegetation and ground surface roughness at very high levels of precision. The technology is sensitive enough to pick out individual bumps, rocks and boulders on the ground surface with a resolution of 10 cm per pixel.

The result of a LiDAR data collection effort is a 3-D ‘point-cloud’ containing millions of points that record the longitude, latitude and elevation of the structural features that make up a given landscape. When combined with the LiDAR-derived landscape conditions, firefighters can apply existing route-finding algorithms to the data to identify the path of least resistance.

LiDAR data currently aren’t well-suited to real time mapping of evacuation routes, because they can take a long time to process and coverage is limited in some regions. However, land managers in areas with high wildfire risk could prepare the data ahead of the fire. With the LiDAR information in hand, firefighters could run the route-finding software to identify escape routes in real-time.

“The goal is to turn this into a tool that can be implemented in a realistic sense,” says Campbell. “Because our work is sponsored by the U.S. Forest Service, we hope to get our tools into the hands of people on the ground, and turn it into something that’s used in a fire-fighting scenario.”

Bret W. Butler of the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula, Montana also contributed to this work.

“and if you don’t like how the Forest Service is funded, call your congressional representatives. They are the only ones who can change the situation.”

We do, but nothing changes.. congress is the most dysfunctional part of government.

If you go to Dr. Dennison’s webpage, he says he provides reprints on request. You should note he had to buy those copies from the publisher so be considerant in how many you ask for.

https://geog.utah.edu/people/faculty/9-philip-dennison.html

And if you don’t like how the Forest Service is funded, call your congressional representatives. They are the only ones who can change the situation.

The Forest Service is at a crossroad. Here in western Oregon they have stopped selling timber and as a result they don’t have the money ( according to them) to protect and preserve the forest, which if i recall is the reason the forest service was given the job on managing OUR land and forests. Clearly, in this heavy forested country this new let everything go to hell while we purchase studies is not producing anything really worthwhile. They have burned at least 3/4 of the Siskiyou NF in the last 15 or so years. It happens that in this time they quit all logging, road maintenance, no longer do brush disposal work on an on going basis, closed campgrounds and trash removal services, and tell the public the forest will be fine if we make sure none of you folks go there. Other than in active firefighting, you will not see any sort of Forest Service crews doing any work in the forest at all anymore, and it is certainly not because there is no work in need of doing.

Across the west all the federal land agencies more and more are running the public off, not doing any sort of real prevention work with regard to fire, flood, or erosion and holding giant camp outs each summer keeping an eye on fires they don’t fight until they are big enough to provide steady work until the rain returns and ends the party. I’m sure there are folks on here that have strong feelings about this perception, but here in southwest Oregon more and more people are beginning to understand that the USFS is the very worst sort of neighbor they can have. If they have a fire start and it burns you out, it is your fault for being there and not in town where you belong. If the fire starts on you and gets out and on them, you bought all the costs they are really really good at adding up, when they get that done, so are you. Around 80% of Oregon land is being “managed” by the feds, who weather stated or not, are doing everything possible to make sure no resource based industry survives. The state and our elected “servants” told us tourism and recreation would replace good paying timber jobs with a vibrant service economy… well not so much… We are smoked out in the travel season, forest roads are not passable, no campsites except for the most basic and unwelcoming and an attitude that the motives and means of their management is not something the public is qualified to comment on or insist be changed. So all of you that work fire, your work is important, your service is honored and valued. That said your voice must be heard by the policy folks and politicians, you know better work containing there conflagrations can and must be done, so let’s get to it and make it work for everyone and not just the activist that want no people permitted in the forest at all.

Thanks for the summary Bill, as a researcher I believe it is our responsibility to explore all potential avenues and solutions to the question we are facing. This was the case of the study exploring the use of LiDAR as a tool to identify safety zones. Spinoffs from this work have helped us understand not only how LiDAR might be useful for improving firefighter safety but also how vegetation density, slope and trail qualify affect escape route effectiveness. I agree whole heartedly that we as a culture and agency can do more to enhance firefighter safety. But as you eluded to in your comments tax payer $’s are limited. Thus we try to do the best we can with the limited funds we have. If you wanted to contribute more, I suggest you plead to the wildland fire community for stories, anecdotes and pictures of safety zones that have been identified, built etc. They don’t have to have been used, but rather just considered. The information should include a description of the fuels, weather and fire behavior. With this information we could add to a collection of understanding about what we are using for safety zones and hopefully how we are identifying safety zones. Thanks for your efforts.

Very interesting use of evolving technology. One thing I wonder about is the philosophical swing from “put ’em all out” to “let ‘er burn”. Can we assess conditions for wildfire environments before we apply a philosophy? Early intervention can and has prevented these huge devastating wildfires from sweeping whole environments. Also with the decreasing number of employees on BLM and National Forest lands we cannot adequately manage the increase in numbers of people who are responsible for 75-85% of all wildfires. Reducing access, reducing the number of motor vehicles and more boots on the ground would help. Just the evaluation of an Old Broad.

Having worked in three different Regions in the course of 36 years prior to retirement, one common thread that I have seen tugged on repeatedly, is the “reducing access” approach.

Lack of access, or the closing off of existing access is a hot topic here in Montana. Citizens have been led to believe that the NF’s, BLM, and School Trust Lands, belong to the citizens, and are fed up with watching them be slowly closed off.