Fitness tracking data from 29,928 individuals representing 421,247 individual hikes, jogs, and runs on trails in and around Salt Lake City was used to calculate travel rates on slopes. Researchers hope their findings can be used to help develop a smart phone app that would suggest to wildland firefighters the best escape route if faced with a possible entrapment.

Funding provided by the U.S. Forest Service and the National Science Foundation, helped Michael J. Campbell (Fort Lewis College), Philip E. Dennison (Univ. of Utah), Bret W. Butler (USFS), and Wesley G. Page (USFS) complete the research which is summarized in their paper, “Using crowdsourced fitness tracker data to model the relationship between slope and travel rates.”

They undertook the study basically because it had not been done before using a large amount of raw foot travel data and the information is needed to develop an app that can enhance the situational awareness of firefighters. Some preliminary work was done two years ago by some of the same researchers. They used Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology to analyze the terrain slope, ground surface roughness and vegetation density of a fire-prone region in central Utah, and assessed how each landscape condition impeded a person’s ability to travel. At the time, Department of Geography professor and co-author of that study, Philip Dennison, said, “Finding the fastest way to get to a safety zone can be made a lot more difficult by factors like steep terrain, dense brush, and poor visibility due to smoke. This new technology is one of the ways we can provide an extra margin of safety for firefighters.”

The researchers felt they needed more accurate travel rate data to build on their previous work to calculate the best escape routes.

The data used in this study were obtained from Strava, a popular fitness tracking and social networking app that allows users to track their movement while hiking, running, and cycling using GPS on phones or fitness tracking devices to compare their travel rates to their peers. The company aggregates and anonymizes the data and makes them available to planning organizations and researchers. The information used in the study represents hiking, jogging, or running a combined 81,000 miles.

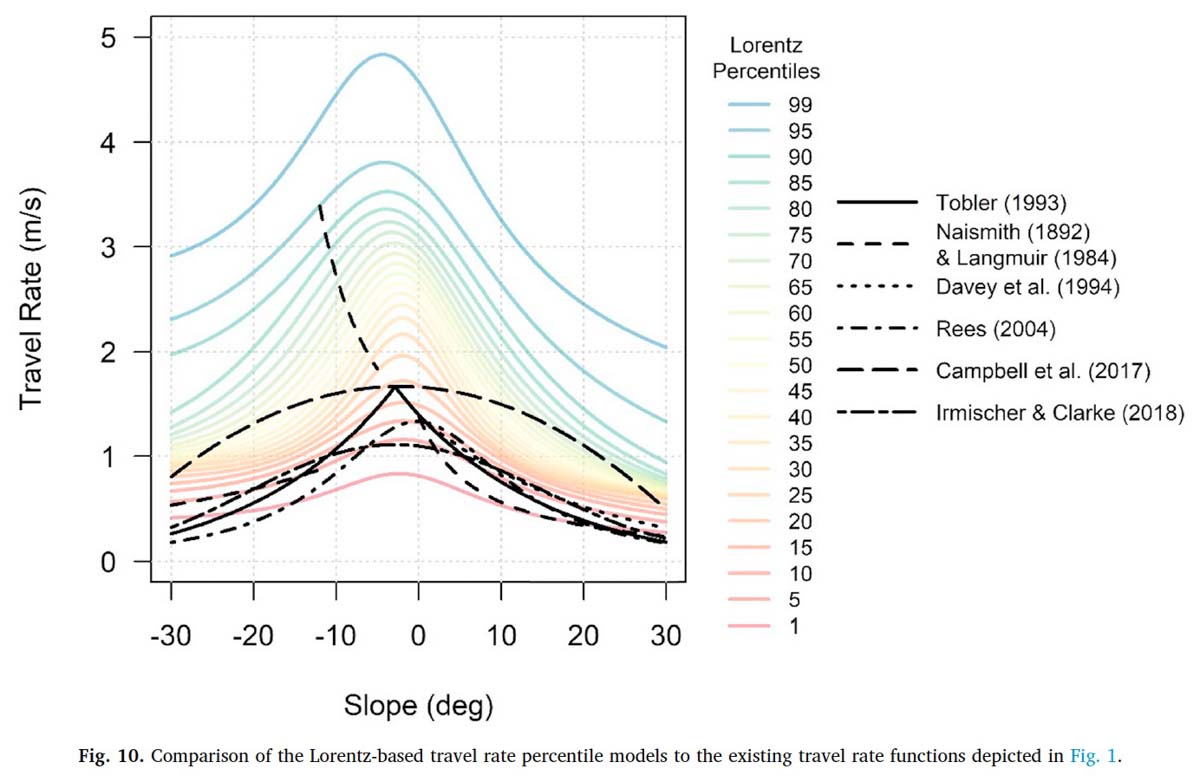

“This will revolutionize our understanding with how terrain affects pedestrian movement,” said Michael Campbell, assistant professor at Fort Lewis College and lead author of the study. “From a firefighter perspective, under normal conditions a fire crew may have ample time to hike to a safety zone, but if the sh*t hits the fan, they’re going to have to sprint to get there. We tried to introduce predictive flexibility that can mimic the range of conditions that one might need to consider when estimating travel rates and times.”

“Calculating how quickly people move through the environment is a problem more than a century old. Having data from such a large number of people moving at all different speeds allowed us to create much more advanced models than what’s been done before,” said Phil Dennison. “Any application that estimates how fast people walk, jog, or run from point A to point B can benefit from this work.”

According to the results of the study, a slow walk on a flat, 1-mile (1.6 km) trail takes about 33 minutes on average, whereas that same level of exertion on a steep, 30 degree slope will take about 97 minutes. On the other end of the spectrum, a fast run on a flat, 1-mile trail takes about six minutes, as compared to 13 minutes up a 30 degree slope. People move most rapidly on a slightly downhill slope, and travel rates were faster for downhill than uphill movement. For example, walking down a steep slope of 30 degrees was done at the same speed as walking up a slope of 16 degrees.

“For wildland firefighters, the slope of the terrain is largely what determines the most efficient path to safety, and dictates how long it’s going to take,” Mr. Campbell told Runner’s World. “Our goal is to provide firefighters with the ability to press a button on their phone and not only map the best route to safety, but also provide a travel time estimate.”

Of course hiking times on established trails is not always completely transferable to the situations faced by wildland firefighters. Presumably ground surface roughness and vegetation density from the earlier work will be factored in when developing the app to make the results more realistic.

Starting this month, the geographers will apply their new models to wildland firefighters. During their spring training, nearly a dozen fire crews in Utah, Idaho, Colorado and California will use GPS trackers to record their movements and log their travel rates. This will allow them to better understand the travel rates of the unique firefighter population, who are often traversing rugged terrain, working long hours, and carrying heavy packs.

An interesting study, lots of variables at play. Any idea what types of crews in Utah under study, as in types 1, or 2? That in itself is sometimes a huge difference. Look forward to the results.