Above: Figure from “Experiments on Wildfire Ignition by Exploding Targets”, by Mark A. Finney, C. Todd Smith, and Trevor B. Maynard. September 2019.

Researchers with the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives detonated almost 100 exploding targets to gather information about how likely they are to ignite a wildfire.

Exploding targets consist of two ingredients that when mixed by the end user explode when shot by a gun. They have caused many fires since they became more popular in recent years, have been banned in some areas, and caused the death of at least one person. In 2017 an exploding target started what became the 46,000-acre Sawmill Fire southeast of Tucson, AZ. After the ingredients are combined, the compound is illegal to transport and is classified as an explosive by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives.

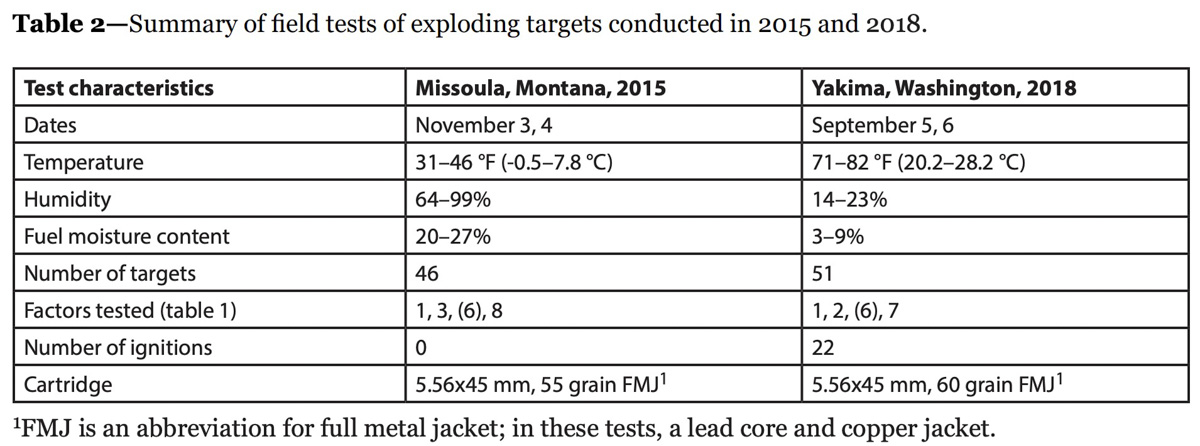

The tests were carried out in 2015 and 2018 by shooting a high powered rifle at the targets — 46 tests in 2015 and 51 in 2018. The results could not have been more different in the two batches of tests. There were no ignitions of the nearby straw bales from the exploding targets in 2015 (zero percent), but there were 22 in 2018 (43 percent). The weather conditions made the difference. In 2015 the temperature was 31 to 46 and the relative humidity was 64 to 99 percent. During the 2018 experiments the temperature was 71 to 82 and the relative humidity ranged from 14 to 23 percent, conditions much more conducive to ignition of vegetation.

The experiments in 2018 were carried out with 5.56×45 mm ammunition, which is used in some AR-15 rifles.

The researchers’ findings can be found in “Experiments on Wildfire Ignition by Exploding Targets”, by Mark A. Finney, C. Todd Smith, and Trevor B. Maynard. September 2019. (7.3 MB file)

The most common ingredients of exploding targets are the oxidizer ammonium nitrate (AN) and for fuel, aluminum powder (AL). Commercially available exploding targets have various concentrations of aluminum which is what actually burns during the explosion, which generates temperatures of about 6,700 °F.

The testing showed a direct relation between the aluminum content of the products and the prevalence of ignition and visible burning aluminum in the explosion.

The AL content of the target mixture had an effect on ignition of the straw bales:

The popularity of these products has led to a wide range of formulations to include more rimfire products that rely on increased metallic fuel content for sensitivity. The testing did show a direct relation between the aluminum content of the products and the prevalence of ignition and visible burning aluminum in the explosion. Wildland fire investigators considering an exploding target hypothesis for a fire start should be aware of the range of products available and how aluminum content, mixing, and other variables might impact the performance of the product and the likelihood of ignition. Tannerite is one of the most common commercial brands of exploding target, but with only approximately 1.6 percent AL, it is among the least likely to cause ignitions compared to brands or formulations with higher AL concentration.

During the tests in 2018 researchers used mixes with AL ranging from 1 to 10 percent.

Some of the first exploding targets had to be shot by a high-velocity projectile fired from certain center-fire rifles. Variants are now available that can be shot by rimfire cartridges (e.g., .22 Long Rifle) or pistols. These targets rely on a greater percentage of AL or other ingredients to increase sensitivity to initiation. Rimfire targets have been found with up to 25 percent AL.

The researchers had some tips for fire cause and origin investigators:

Informal observations during this research suggested that the use of exploding targets may leave evidence in and around the blast seat. The research team observed some shattered pieces of the plastic containers in and around the blast seat following testing. This plastic, which exhibited exposure to high temperatures, appeared to have embedded AN on one side of the plastic. The team also observed unconsumed AN prills on the ground around the blast seat during testing. While this in no way means such evidence is present after all exploding target explosions, fire investigators should be cognizant that potential forensic evidence may be located around the blast seat that should be collected and documented.

In addition to documenting physical evidence that can aid investigators, another thing this research accomplishes is it makes it easier to prosecute cases where a defendant is accused of starting a fire by shooting at an exploding target. It proves that the devices CAN start a fire. Prior to this, an attorney might argue, exploding targets do not ignite fires.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to LM. Typos or errors, report them HERE.

Attn: Trevor B. Maynard,

I ran across a study of the above title name, ref USDA Forrest Service Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-104.2013,

of which you were one of the authors.

It was of interest because an analytical testing approach was used to sort out and put some light on fires started from rifle bullets.

My interest was more on does 22 LR 40 grain solid lead bullets cause fire starting in dry brush, more typically from Blazer ammo at 1235 fps.

Your artical –mentioned it in some bullet ammo descriptions– but gave no data or Statistical probability of starting a fire from that specific 22 LR ammo.

Would there be anything you can add to the probability of such 22 LR lead RN, mv 1235 feet per second in starting a brush fire.

We have a situation in southern California—- that seems to band nearly all shooting in San Diego County because of fire season,

I was just wondering if there is any actual data that would show /prove such above 22LR ammo would start such fires.

PS. I am an Engineer, and must show data/test results to substantiate all statements— or is the overall band on all shooting

is just– gun control– bureaucratic assumptions– with no credibility.

Thank You

William H Weitzel

Sir please take a look at the following Research paper that describes fragment tamps based on velocity and bullet material.

Rocky Mountain Research Station

Research Paper RMRS-RP-104

August 2013

So can we just ban tannerite already? Yes I know that it’s great juvenile fun to blow stuff up but aside from the fire danger it also leaves a considerable amount of pollution behind and the racket is disturbing to wildlife for a large area around the blast.

A break-thru in scientific research! When fuels are cool and wet, they don’t burn but when they are hot and dry, they do. Who woulda thunk it?