Maps are a great way to communicate with a public that may be starving for information about an ongoing fire, or to inform them about conditions that could lead to more fires. They can provide information very quickly — if thoughtfully created.

The two maps below distributed by Geographic Area Coordination Centers (GACC) on Twitter attempt to warn the public about the elevated danger of wildfires caused by actual or predicted lightning. I would venture a guess that the general public would have great difficulty figuring out what part of the country they represent based solely on the images. There are no state boundaries that can be easily identified and no cities or highways to make the guessing game easier. The polygons within the maps (which are not counties on the RMACC map) do not convey any worthwhile information to the casual Twitter user, only adding to the confusion.

Wet/dry thunderstorms in E/Co today; lightning activity in the RMA for the past 24 hours showed 10,714 strikes. Strikes blanketed CO, S/WY & E/KS. Western SD saw strikes across the western part of the state w/some in central SD. pic.twitter.com/6pqenkCKFn

— RMACC (@RMACCinfo) August 30, 2020

Fire Potential Impact Map for Sunday-Tuesday, 8/30/2020 – 9/1/2020.#gbcc #greatbasincoordinationcenter @GreatBasinCC

Daily Outlook video briefing located at: https://t.co/PNWyKaeHDh pic.twitter.com/lowcYgoz3V

— GBCC News and Notes (@GreatBasinCC) August 30, 2020

I am a harsher critic of maps than most, having spent many fire assignments as Situation Unit Leader and Planning Section Chief, producing maps for firefighters and the public. Map making continues at Wildfire Today, producing graphics to illustrate the location of fires.

When the public sees smoke or they hear about new fires, many of them have one overriding question. Where is the fire? Unless they have property in the area, the typical person does not need to know that the fire is 300 feet west of Forest Service Road 24D3. They also don’t care about division breaks or helicopter dip sites. They need a map so they can figure out, in many cases, where the fire is in relation to them or their community. A map that is zoomed in so tight that the geographical context of the fire can’t be seen, is often not helpful to the public. A person can get oriented more easily if they can see highways and one or more cities/towns/communities. But if the incident is in a very remote area, that can be difficult.

I visited InciWeb today and found some good, bad, and ugly examples. All of the images below were large files that needed to be reduced in size to show here; the original images have more detail.

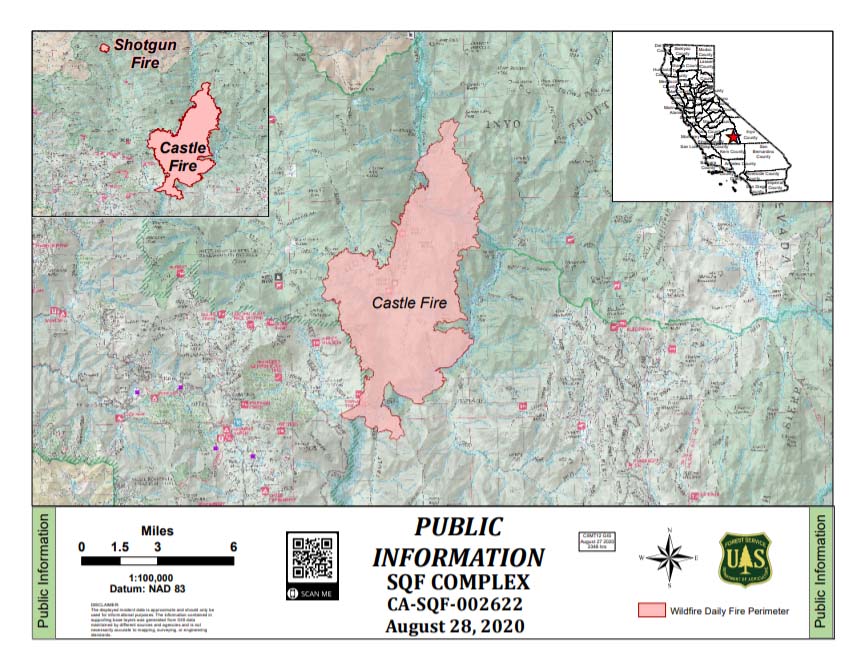

The map below of the Castle and Shotgun Fires on the Sequoia National Forest appears to be based on the standard Forest Service recreation map that forest visitors can purchase — on paper. It is shaded, which may represent vegetation and/or topography and also includes virtually every Forest Service site or feature that exists, including dirt roads. The result is clutter that unless a person has a high-resolution copy of the image and plenty of time, it is difficult or impossible to find paved roads, highways, or communities that could help a person to get oriented. At least it has a vicinity map at upper-right so we know it is in central California.

The base map used for fire public information maps should not be topographical lines or the standard F.S. recreation map.

The map of the Griffin Fire below is better. It is zoomed out providing geographical context, and is not cluttered. But much of the very small text is difficult or impossible to read.

The map below shows five widely separated fires in Arizona so it has quite a bit of context. It shows many, many dirt roads, but that helps to show the location of the three fires on the east side. I don’t know that the shaded relief background adds value, but it has a vicinity map, which is a plus. Overall, a very good map.

The map of the P515 and Lionshead Fires in Oregon deserves praise for its simplicity and lack of clutter. The colors showing ownership are all very different from each other, making it simple to compare them to the helpful legend. It is effective and easy to comprehend. The Lionshead Fire is so close to the edge it makes me wonder what is just off the map to the west. Probably more of the same, but still…

(One of my pet peeves is when six similar shades of brown, for example, represent different features. Not a problem on this map.)

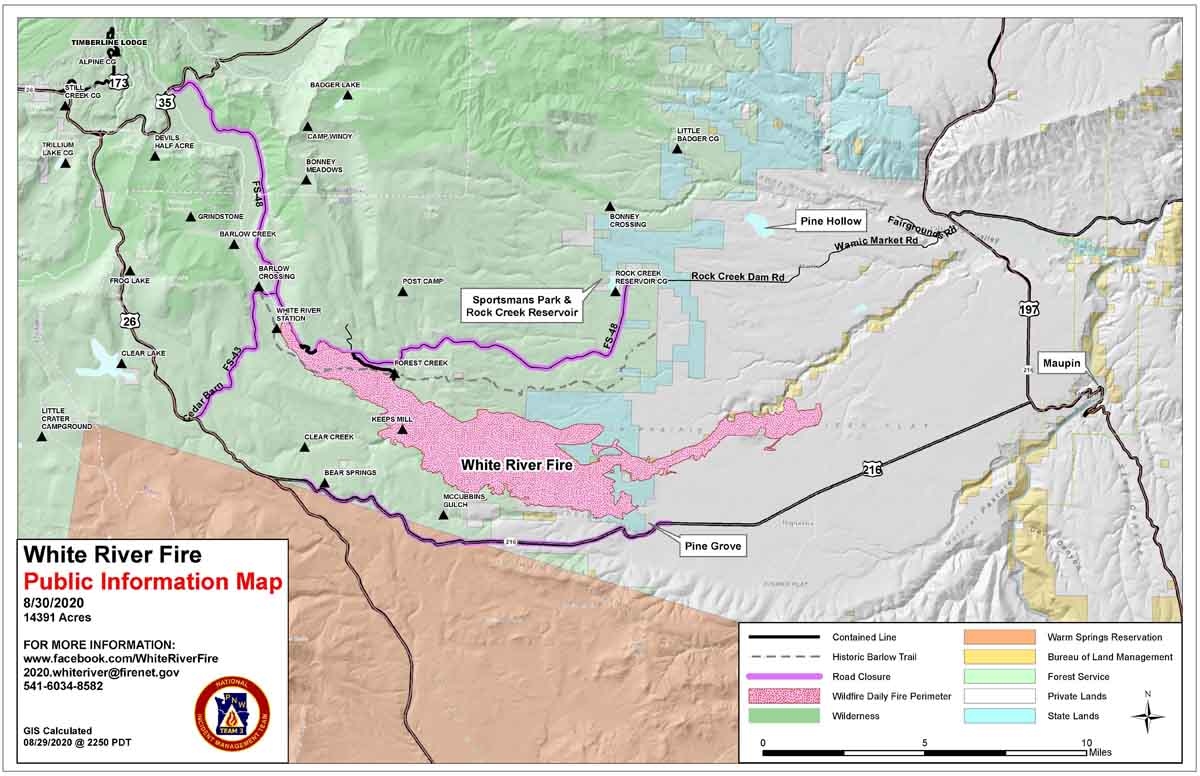

The best map that I ran across during my quick perusal of InciWeb today is the White River Fire on the Mt. Hood National Forest in Oregon. The map maker made sure to include at least one community and several highways. They even went the extra step of adding three labels to features with which the public may be familiar. It is pleasing to the eye, has a useful legend, and the highways near the fire are identified. Even though much of the fire is on Forest Service responsibility land, they resisted the urge to use the FS recreation map as a base map. Great job, White River Fire. (Contact us and we’ll send you a prize, a Wildfire Today cap.)

This is a wonderful article and an important topic.

As typical, emergency management looks for simple answers for complex problems.

First, it fails to address “Who is this map for?” and “What do they need it for?” Many maps are created for one purpose, but are used for other audiences and other purposes.

“The two maps below distributed by Geographic Area Coordination Centers (GACC) on Twitter attempt to warn the public about the elevated danger of wildfires caused by actual or predicted lightning.” Did the person creating the map know that it would eventually be tweeted out to be interpreted by the public? Is this a fault of the GIS person, the organization, the tweeter, or those reading the map? If this tweet tells you the map shows high amounts of lightning, where are you deciding that the map is “…attempt[ing] to warn the public” of anything? I understand the context may have been lost in the tweets before or after, but pity the poor mapper who just wanted to say “Here’s where the lightning was.” for the wildfire audience.

“I visited InciWeb today and found some good, bad, and ugly examples. All of the images below were large files that needed to be reduced in size to show here; the original images have more detail.” That statement alone indicates that the files were never intended to be reduced to a twitter tweet, conveyed much more information that is indicated in the post, and were never intended as for a public audience. No wonder, they are not great maps.

But that is one of the great misunderstandings of map creation. The map was never created for “me” to use. It was created for groups to use. Firefighters. Incident Management Teams. Evacuation areas. Fire Spread. Dipping points. It was never intended for one family to say “my house is gone”, one neighborhood to say “here’s the safe evacuation route”, or one person to show “I am exactly here on this map”.

No wonder the maps providing the exact information each single person needs. Different audiences need different maps. Different uses need different layers. We need to understand that who, what, when, where, why, and how each requires different maps of different scales with different references, for different time projections and different reader abilities.

Which is why mapping is difficult.

Maps! Don’t get me started. Oooops. too late… I’m starting. I just returned from a 17 day assignment as a FOBS on one of the still active record setting fires in California. This is a State responsibility fire, with a Cal Fire Incident Command Team running the show. Before my map critique I’ll share a little of my background… 2020 is my 42nd fire season, 35 with CDF/Cal Fire, 7 more with a local government department. I’ve been a qualified FOBS since the early 1990’s, I spent 5 years as the GISS Lead on a Cal Fire Incident Command team (2007-2012); I’ve been an Engine Captain, an inmate Crew Captain, a Helitack Captain and a Unit Pre Fire Engineer. My point is, I’ve used maps on the lines; I’ve contributed data to the compilation of incident maps, and I’ve personally made OPS, IAP, Progession Maps and all the rest. As a GISS Lead my focus was always and only on what the troops on the lines needed in a map to safely and efficiently do their jobs. (I always assigned PIO and Evac maps to someone on my team). Regardless of the type of map one is charged with making, the key principle is meeting the needs of the target audience/end user. Let me offer an example.

During my first FOBS shift on this ongoing fire I noticed immediately that the IAP maps had nothing but contour lines highlighted by hill shading. When I asked the young Sit Unit Leader why they weren’t using standard USGS topo maps as the base he said “… this contour layer looks pretty”. Looks pretty! USGS topo maps provide an incredible amount of information well beyond the topographic contours. USGS maps are a critical component of situational awarenss. Fighters on the line benefit from that information. This incident’s IAP maps were seriously deficient – no geographic feature names, no roads, no structures, no water course symbology, no section/township lines and numbers, none of the information provided in a USGS topo… nothing but “pretty” contour lines. This Sit UL is so enamored by new technology, and so lacking in fireline experience, he has failed to concern himself with what the fighters in the field need. He clearly doesn’t understand what his target audience / end user needs to function safely and efficiently. Every day on the line I spoke with at least one Div Supe, crew Captain or Strike Team Leader who told me the IAP maps were useless. After several days I was finally able to convince the GISS lead to put the section lines on the map; so we in the field at least had those to use as a reference when relaying information concerning the location of resources or fire progression or firing ops or dozer lines etc.

Putting oneself in the boots of the end user and trying to understand the needs of your customer is key to building an effective, informative, useful map.

While not mentioned in your write up, the fact that many incident maps can be accessed and uploaded by incoming resources prior to arrival at the incident is a huge improvement from where we used to be…..I will take a poorer quality map any day over nothing…not that I disagree about your take on quality of product.That should come out in the team de-brief…right….lol….

Being out on the line or even public maps I get annoyed at the lack of section lines – even if we don’t identify locations via the section, I know that square is 1 mile x 1 mile and is 640 acres. I also never see a map scale ratio – 1:24,000 or 1:whatever. Two useful things.

This is fascinating and informative-thank you!

I agree with your observations 100% … as a former PIO on regional and national teams I was always grateful to have a Tech Support shop that actually realized the mapping needs of a Div Sup are way different from the needs of the surrounding public. It requires extra effort to produce another map set for the Public but it is essential.

Sometimes, (if we could find some local agreement), we would ask the GIS folks to insert local names in parentheses next to the “official” names of landmarks.

Kudos to Teams that make the extra effort.

Thanks for highlighting the problem of indistinguishable colors. As one of many folks with reduced red/green color vision, when I see one with pale orange, light orange, orange, dark orange, red, dark red….it’s meaningless. Using very different colors, or as suggested above, something like cross-hatching, is far superior for a lot of folks.

Bill

Thank you for the great maps. Keep it up!

Nice article! I’ve always been a map person myself (never use GPS) ever since I can remember. Thanks for giving props to the Oregon mapmakers.

Were I not a long time California Native, I would not be able to guess that the Castle Fire is in the vicinity of Lake Isabella and heading up into the Kern River Canyon. The Golden Trout Wilderness is off to the left in Inyo Co. section of the Sequoia NF.

Seeing the town of Madras and the US Hwy 87 symbol on he left edge of the Lion’s Head fire tells me its in north part of Oregon west of the main Hwy between California and the Columbia River that traverses the center of the state and continues through Washington.

With the Walbridge Fire burning north of the Russian River here in California, it was frustrating to find only reference to roads seldom traveled by non-residents until I pulled out a Thomas Brothers map book to see where the mentioned location were, but that did not help in identifying the fire boundaries until our local daily began including good maps with the latest edition–6 or 7 days after the fires were reported. CalFire rarely updates its website more than once a day, although it held both morning and afternoon press conferences that were informative, and Radio Station KSRO managed to get additional updates from the County Emergency Coordinator.

Because your maps have been the best, I’ve sent a number of your reports to friends in the Phoenix area and within California who were close by over the past two months, as well as your Projected Smoke Drift projections so they would know the actual fires were not close by.

Since my fire assignment was FIO for two thirds of my Forest Service career, I’ve been less than pleased with the quality of fire information over the past two decades and truly appreciate the quality of effort you are making.

THANKS FOR THE HOURS OF WORK. WE LIVE AT THE BASE OF THE BIG HORN MTS IN WYOMING AND THUS WE NEED TO WATCH THE WARNINGS AND FIRES, IF WE HAVE ANY.

THIS HELPS TO EXPLAIN WHERE THE SMOKE COMES FROM

MANY THANKS AGAIN

SHELL,WY

Timely in selecting the inferior Castle Fire map. I had resorted to creating my own maps to share information about this very fire, exactly for the reasons stated. At times I’ve created 3 maps of the same area, detailed to zooming out. The Castle Fire info and map seemed to be overly slow in coming out, much to the frustration of many locals in the nearby foothills and mountain communities needing to know if they would be evacuating. When I finally saw that map I was shaking my head.

Color shades have always been a gripe for me, and I’ve wondered why not add a cross-hatch, dots, etc. Take a step back and look at the map from a civilian’s perspective and ask if it’s fitting the need for everyone. I hope some of those folks will be reading this.

I agree, both with the varied quality from fire to fire, and to the call that Oregon’s was the best. I think that the touch of adding some local landmarks to help people orient is immensely helpful!

A good map is always a treat. The ability to create something that is both operationally useful as well as of “wall hanging quality” for the command folks is a real talent. Busy maps are just as useless as pretty maps with little valuable info. Map making is as much a art as a science. Find a good map maker and treat him like gold as it will pay off for you in spades on any incident as well as back at your base.