Colorado’s wildfire risk map was so inaccurate that state officials just about ignored it — for many years. The map was outdated, especially in western Colorado, where 3+ million acres of forest was covered in beetle-killed pines.

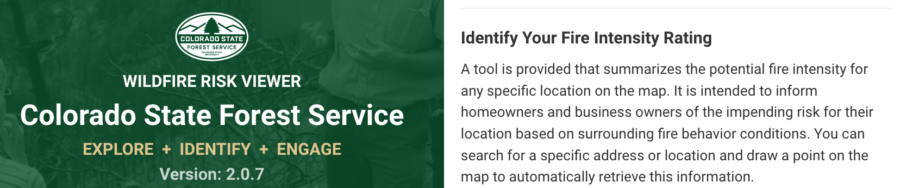

Carolina Manriquez, a lead forester with the state’s forest service, said they were supposed to use the state risk map, but they knew it was not accurate and therefore couldn’t rely on it. As the E&E News recently reported, an infusion of $480,000 in state funds resulted in a new Colorado map with updates including pine beetle damage and densely populated mountain towns.

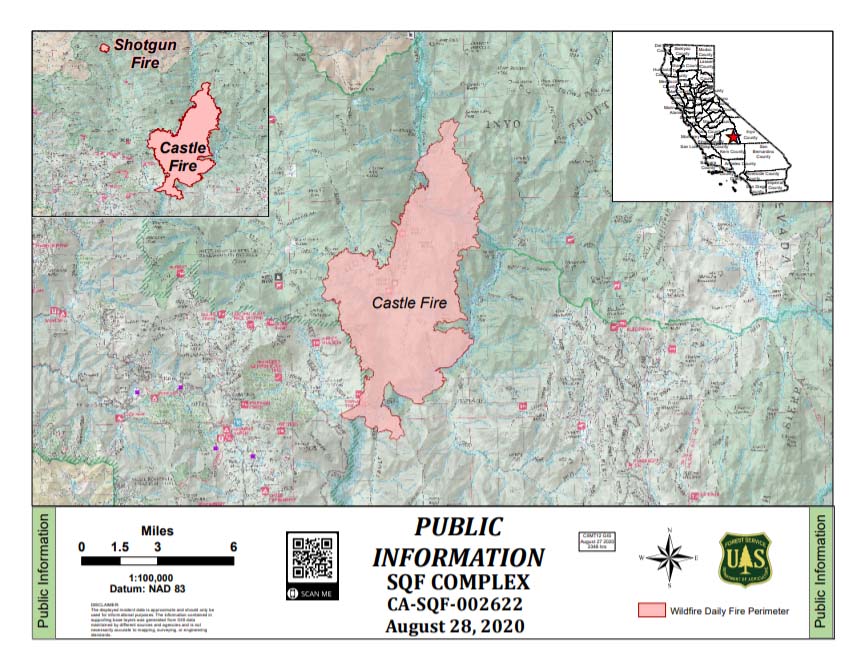

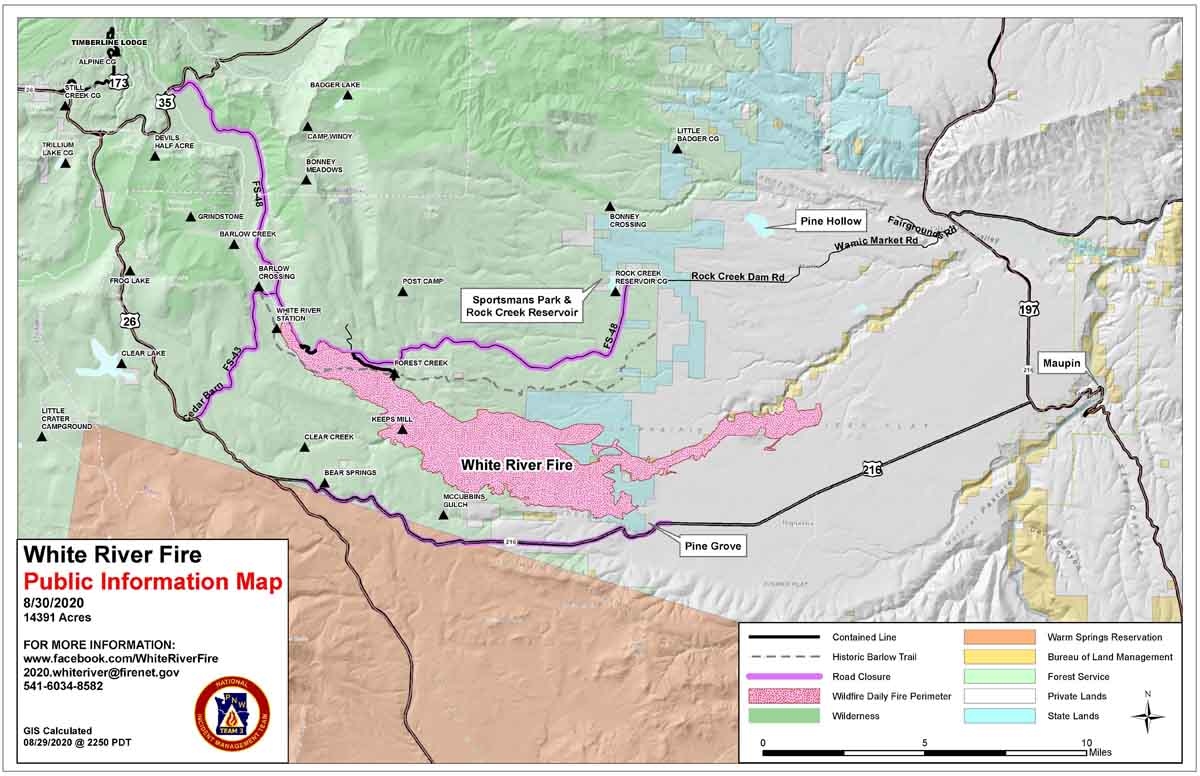

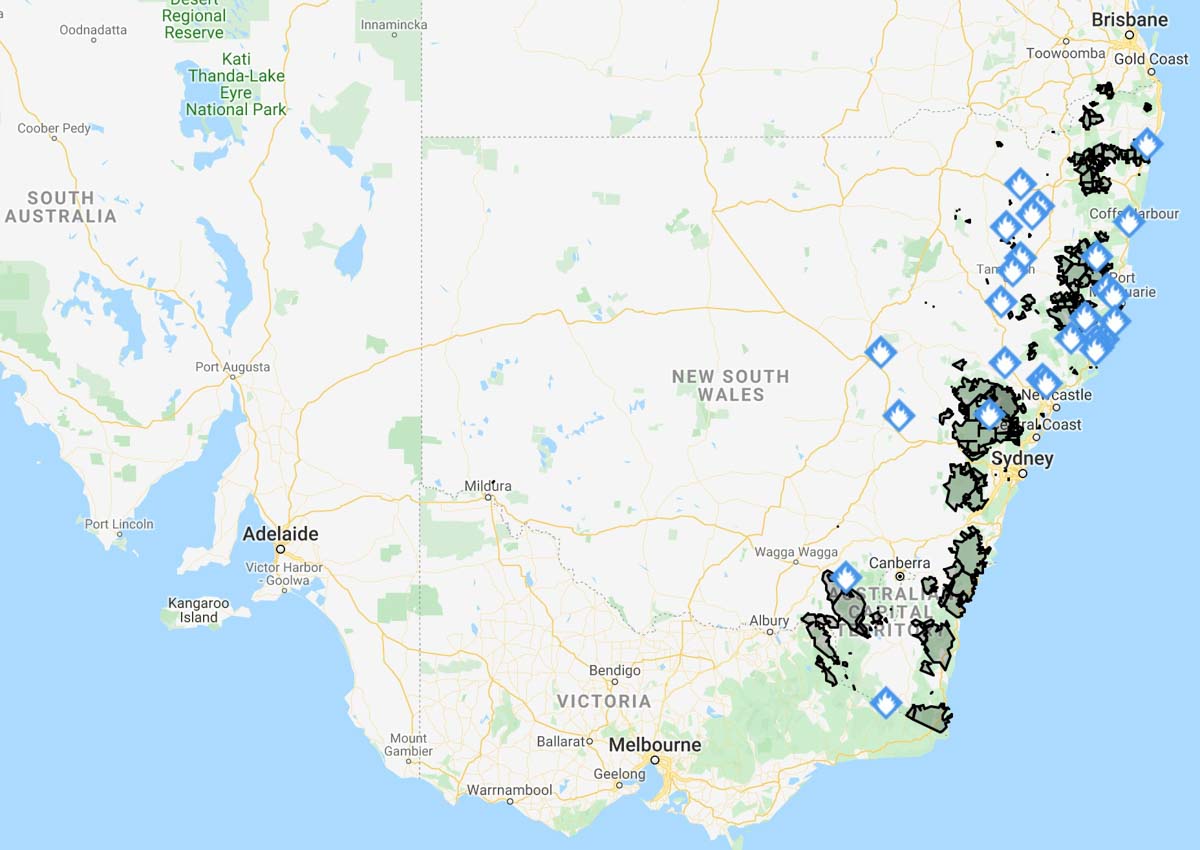

Including 2017 and 2020, when annual wildfires burned more than 10 million acres, the last decade has marked some of the worst fire seasons in history. The risk is compounded by both climate change and growing wildland/urban interface areas, particularly in the West. Some states — including Colorado, Oregon, Utah, and Texas — have moved toward ensuring their fire risk information and maps are updated and more accurate, displaying areas of highest risk and most in need of prevention and mitigation.

“There is a slowly growing push among different states to do this,” said Joe Scott, founder of Pyrologix in Missoula. The firm provides utility wildfire risk assessment, catastrophe modeling, fuels treatment prioritization and management, and exposure analysis.

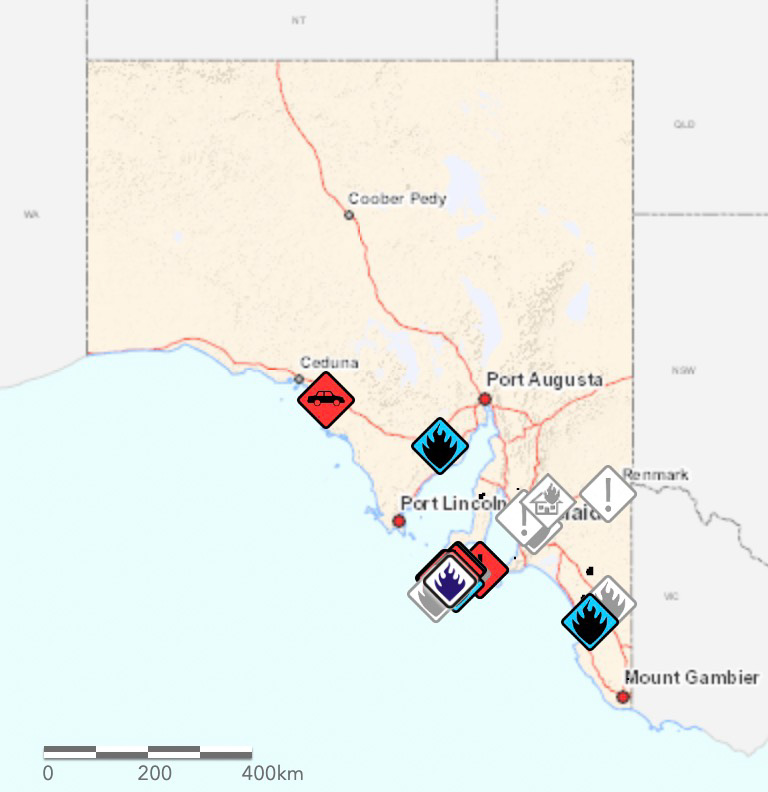

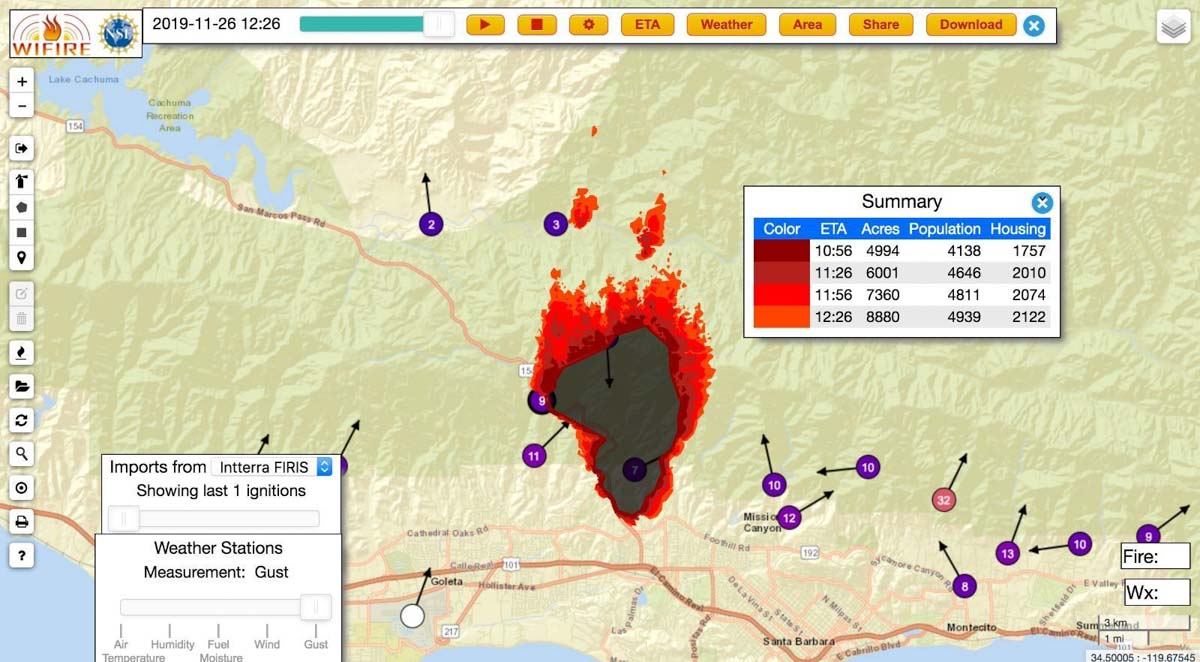

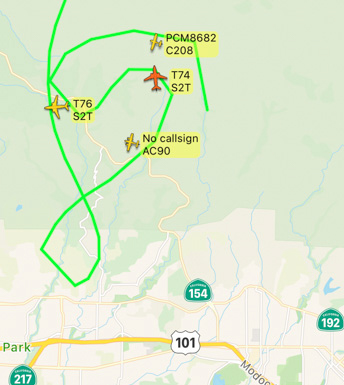

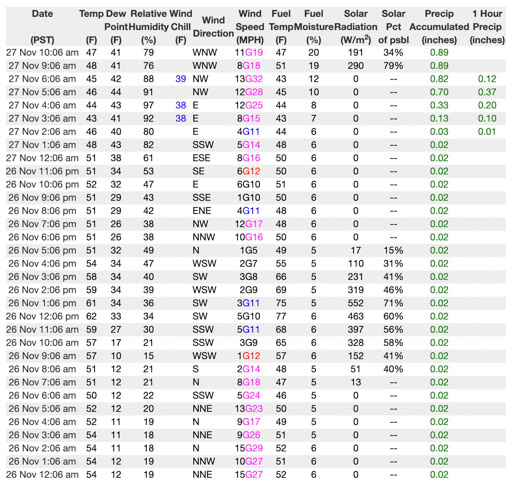

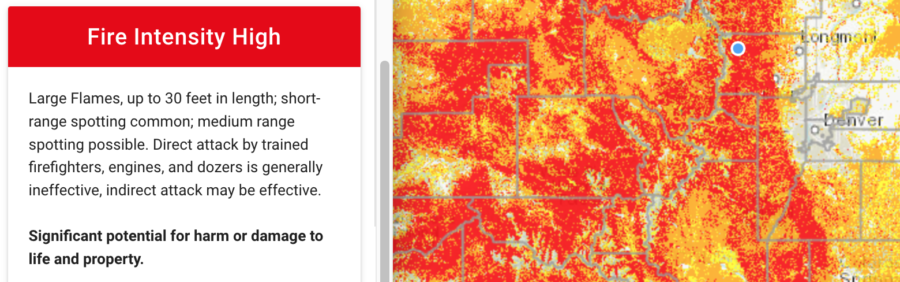

To improve wildfire risk maps, many states are partnering with firms such as Pyrologix that can build public-access display of fire risk data and conditions. Using satellite imagery, census information, and other data, advanced tools can determine locations and ranges of ignition probability and fire intensity, along with threatened resource types. Gregory Dillon, director of the USFS fire modeling institute, says the state-specific maps are not a duplication of federal fire maps, but rather a more refined product.

The Kansas Forest Service unveiled in September its new wildfire risk explorer, a digital interactive map that provides a detailed look at statewide fire risk. The effort began in 2018 after several major wildfires including the 2017 Starbuck Fire, which burned some 500,000 acres and destroyed or damaged more than $50 million worth of livestock, fencing, and other resources.

“A lot of state-led efforts are trying to communicate to communities and residents about the risk to private property or municipalities,” said Jolie Pollet, wildfire risk reduction program coordinator at the Department of the Interior.

That’s slightly different from federal mapping efforts focused on protecting federal lands, Pollet said. State-focused mapping can assess evacuation routes, encourage homeowners to reduce their risk, and improve prepared applications for federal grants. State improvements such as those in Kansas also help forestry and fire officials allocate limited resources to focus on the highest priority areas.