September 25, 2020 | 5:23 p.m. MDT

This article was first published at Fire Aviation September 24, 2020

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has released an interim report about the January 23, 2020 crash of a C-130, Air Tanker 134, that killed the three crewmembers on board. This follows the preliminary report the agency issued in February, 2020. The aircraft was known as Bomber 134 (B134) in Australia.

“The interim report does not contain findings nor identify safety issues, which will be contained in the final report. However, it does detail the extensive evidence gathered to date, which has helped ATSB investigators develop a detailed picture of this tragic accident’s sequence of events,” said ATSB Chief Commissioner Greg Hood.

It was very windy on January 23, with a forecast for the possibility of mountain waves. Before the incident a birddog, similar to a lead plane, and Bomber 137 (B137), formerly Tanker 138, a Boeing 737 that Coulson sold to New South Wales, was tasked to drop on a fire in the Adaminaby area. Based on the weather the birddog pilot declined the assignment. After B137 made a drop on the fire, the crew reported having experienced uncommanded aircraft rolls up to 45° angle of bank (due to wind) and a windshear warning from the aircraft on‑board systems.

After completing the drop, the B137 crew sent a text message to the birddog pilot indicating that the conditions were “horrible down there. Don’t send anybody and we’re not going back.” They also reported to the Cooma FCC that the conditions were unsuitable for firebombing operations. During B137’s return flight to Richmond, the Richmond air base manager requested that they reload the aircraft in Canberra and return to Adaminaby. The Pilot in Command (PIC) replied that they would not be returning to Adaminaby due to the weather conditions.

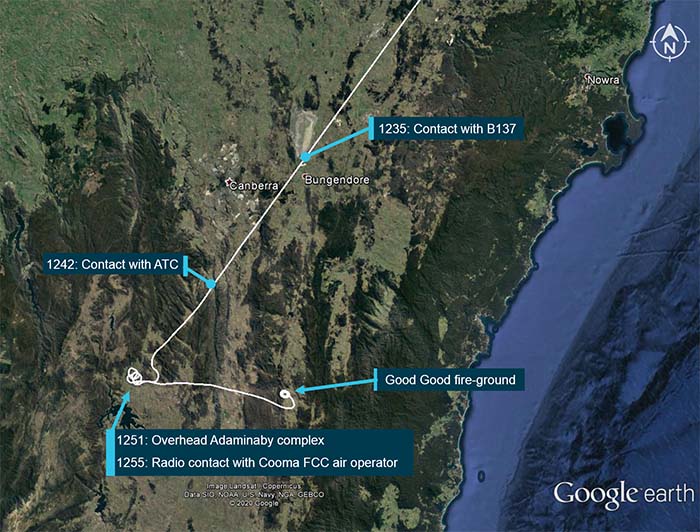

B134 was dispatched to the fire at Adaminaby. While they were in route, the PIC of B137 called to inform them of the actual conditions, and that B137 would not be returning to Adaminaby.

After arriving at Adaminaby the PIC of B134 contacted the air operations officer at the Cooma FCC by radio and advised them that it was too smoky and windy to complete a retardant drop at that location. The Cooma air operations officer then provided the crew with the location of the Good Good Fire, about 58 km to the east of Adaminaby, with the objective of conducting structure and property protection near Peak View. Again, there was no birddog operating with the air tanker.

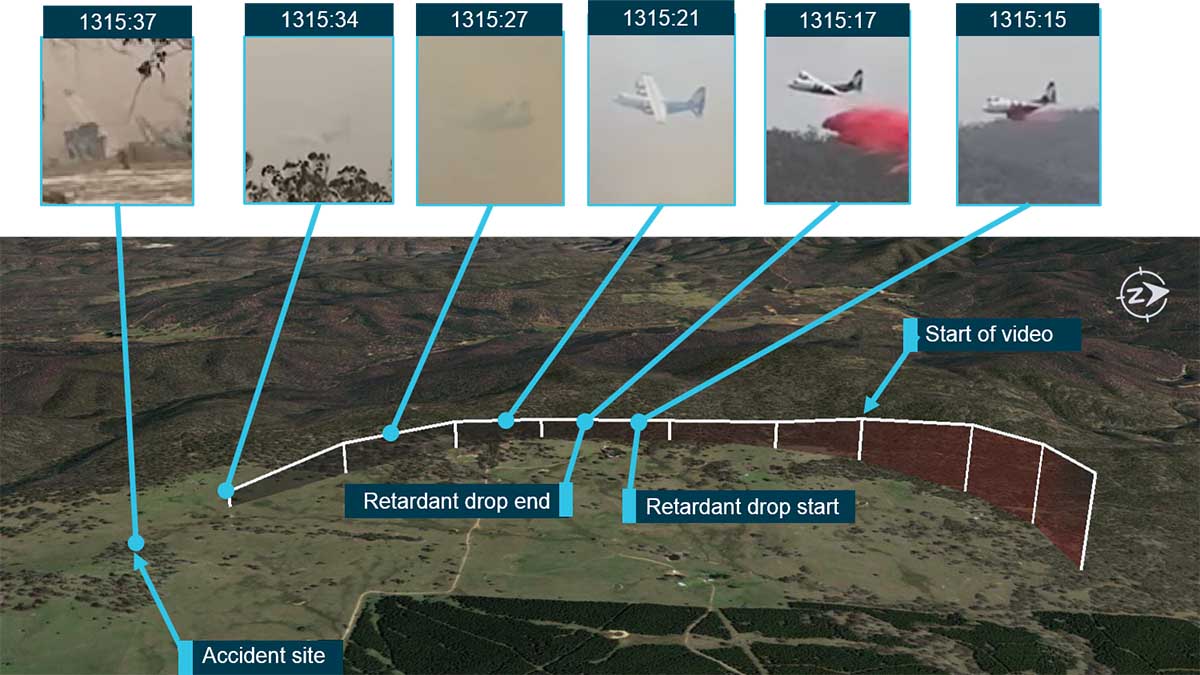

Analysis of a witness video confirmed that the aircraft initially established a positive rate of climb and was banking to the left following the retardant drop, the report details.

After climbing for about 10 seconds the aircraft was then observed to roll from a left bank to a slight right bank. A maximum height of about 330 feet above ground level was reached before the aircraft was observed descending. A further seven seconds later, the aircraft was at a very low height above the ground, in a left bank, before it collided with the ground.

In the video the aircraft is intermittently obscured by smoke, however, it is unclear if the aircraft flew behind the smoke or entered smoke, Mr Hood noted.

The report also notes that at the time of the retardant drop, the aircraft’s recorded ground speed (determined from ADS-B and SkyTrac data) was 144 knots, while prior to the impact, the groundspeed had increased slightly to a maximum of 151 knots.

Mr. Hood said the ATSB’s examination of the accident site and recovered wreckage established no evidence of structural failure or pre-existing damage to the aircraft. The engines and propellers were operating normally.

Weather

A private weather station about 1.3 km from the accident site had recorded winds from the west of 15-16 knots, with a peak gust from the north-west of 43 knots.

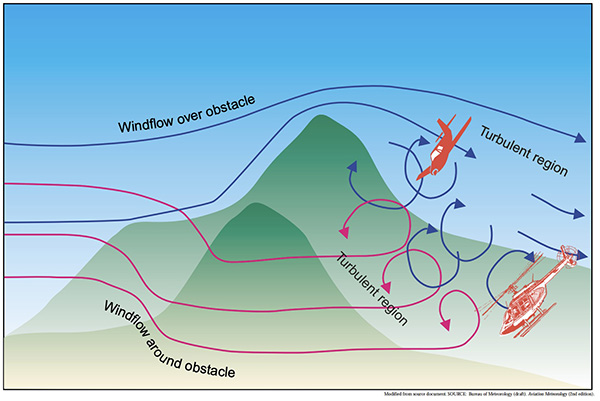

Mr. Hood said a Bureau of Meteorology analysis of the weather conditions on the day of the accident indicated that a cold front was approaching the accident location, with hot and strong north to north-westerly winds ahead of the front.

“The Bureau of Meteorology considered the conditions on the day were favorable for mountain wave development, and satellite imagery of cloud formations confirmed their presence in the general area of the accident,” he said.

“However, from the data available they were unable to determine the severity of mountain wave activity.”

The interim report also notes that the flight crew were appropriately licensed and endorsed, held valid medical certificates, and that there no indications they were fatigued. However, there was insufficient information available to the ATSB about the crew members’ sleep and non-duty activities to estimate fatigue levels with confidence.

Retardant Delivery System

The Retardant Aerial Delivery system (RADS) included a 4,000 US gallon (15,000 L) tank system located within the aircraft’s fuselage. The system could deliver discrete quantities of retardant, dependent on the duration that the doors remained open. It was controlled from the cockpit, with drop controls located on both the PIC and co-pilot yokes.

The drop quantity could be controlled either as a pre-set percentage by the crew, or alternatively, if selected at 100 per cent, the crew could control the amount of retardant released by holding the button until the desired amount was dispensed. The RADS system was designed that, if less than 100 per cent volume was selected, the system would disarm after a partial load drop, and the crew would need to re-arm the system to complete further releases. It was reported that the crew on B134 normally selected 100 per cent volume and released the drop button once the desired amount had been dispensed.

The system also included a guarded emergency dump switch, located in reach of all three crew members, which would fully open the doors and jettison the load in a period of about 2 seconds. Following an emergency dump, the doors would remain open until the RADS was reset by the crew.

Cockpit Voice Recorder

The cockpit voice recorder was recovered from the aircraft and successfully downloaded. However, the audio was from a previous flight when the aircraft was operating in the U.S. No audio from the accident flight was recorded on the CVR.

The power supply for the CVR was fitted with an inertia switch. Inertia switches are designed to stop the recording function by removing power to the CVR when a pre-set deceleration force is detected. The recovered audio was of crew training flights undertaken on May 7, 2019 near Sacramento McClellan Airport, California. The audio included four landings conducted as part of the training in the aircraft on that day. The recording ceased immediately after the fourth landing, and the post-landing taxi and engine shutdowns were not recorded. It was likely that the inertia switch was activated during this landing and consequently disconnected power to the CVR.

Following a CVR installation in an aircraft, supplemental material related to the operation of the CVR must be attached to the approved airplane flight manual. The supplement for the aircraft indicated the CVR conducted a self-test at power up, and the status of the CVR would be presented to the crew on the CVR control unit, located on the co-pilot side console. A CVR system check was not included in any of the operator’s checklists, and none of the operator’s flight crew were aware of the need to check this system status prior to flight.

Aircraft and Crew

The aircraft, a C-130 (technically, an EC-130Q), was operated by Coulson Aviation, a U.S. based operator, with a U.S. registered aircraft (N134CG) and U.S. licensed crew contracted to Australia for the 2019/2020 fire season through the National Aerial Firefighting Centre.

The PIC first obtained aerial firefighting experience as a navigator and pilot while with the U.S. Air National Guard through the Modular Airborne Firefighting System (MAFFS) program. The PIC began working part time for Coulson in 2015 and became full-time in 2017.

The PIC’s logbook, combined with the operator’s records showed that the pilot had a total flying experience of about 4,010 hours, which included 3,010 hours in the C-130 aircraft, and 994 air tanker drops. The PIC had also accrued a further 1,616.8 hours as a flight navigator.

The co-pilot and flight engineer were in the military for 20 and 25 years, respectively. This was the first fire season for both. The co-pilot had a total flying experience of about 1,744 hours, of which 1,364 were on the C-130.

Followup Actions

The ATSB was advised of the following proactive safety actions taken by Coulson Aviation in response to the accident:

- The Retardant Aerial Delivery system (RADS) software was reprogrammed so that the system will not require re-arming between partial load drops where less than 100 per cent volume is selected.

- Updated their pre-flight procedures to incorporate a cockpit voice recorder system check before each flight.

The following was not part of the ATSB interim report

Captain Ian H. McBeth lived in Great Falls, Montana and served with the Wyoming Air National Guard and was still a member of the Montana Air National Guard. He spent his entire career flying C-130’s and was a qualified Instructor and Evaluator pilot. Ian earned his Initial Attack qualification for Coulson in 2018.

First Officer Paul Clyde Hudson of Buckeye, Arizona graduated from the Naval Academy in 1999 and spent the next twenty years serving in the United States Marine Corp in a number of positions including C-130 pilot. He retired as a Lt. Colonel.

Flight Engineer Rick A. DeMorgan Jr. lived in Navarre, Florida. He served in the United States Air Force for eighteen years as a Flight Engineer on the C-130. Rick had over 4,000 hours as a Flight Engineer with nearly 2,000 hours in a combat environment.

May they rest in peace.

Note that investigation is ongoing, crawling through whatever information is available.

Perhaps analysis of turbulence, as was attempted with the Air Tractor crash in Alberta. (Though the preceding aircraft’s experience was available (s/he survived), cause was a particular type of air motion occurring in certain circumstances, substantially created by the fire itself, in this case the fire doesn’t seem severe just too close to buildings).

Note that the ‘bird dog’ airplane could not operate in the winds and turbulence in the region at that time, so the C-130 and a B-737 operated without it – perhaps unwisely, and the C-130 crew declined the assignment at the location the 737 reported trouble with.

Perhaps the C-130 crew were trying too hard, they were low on the drop run (higher on three earlier passes).

Our team was working at the Canberra LAT base, Australia..mixing and loading retardant on SEATS and LATS. We were distressed when we heard of the fatal crash of the C130. It was a crazy day, mixing over 230,000 litres of retardant, a fire at the airport and a DC10 arriving in Australia. BLACK SUMMER was a horrible year for fires, loss of life, animals and land.

Hey Tina,

Without the amazing work of everyone on the ground there would be no air-tankers doing anything…. the unsung heroes in all wildfires are the ‘ramps’ working often in unbearable heat, uber long hours and doing everything at 100% to ensure the crew can lives and structures… Really massive big well done to ALL of you that turn the ‘birds’ around and especially the ‘liquid-loaders’ You all deserve medals for your quiet and hugely unnoticed contribution to the fire efforts… Well done from blighty!! Bravo!

Condolences and prayers to the family and Coulson team mates first and foremost in what has been a terrible year for air tanker accidents. Whilst no assumptions can be made on this one, the initial report heavily weighs towards ‘weather’ being the reason for the accident.

My biggest concern though is in the coordination and accountability of the aircraft tasking from the ground which seems to pay very little attention to the risk being encountered by the operating crew. There seems to be no ‘link’ between the Fire OCC tasking cell, and the weather risk for the area what you are asking the crew to achieve..

Local knowledge of the terrain typically provided by the ‘local’ bird dog especially in regards to mountain wave, rotor and unique environmental issues bespoke to that area is totally invaluable and it’s disappointing to say the least, that the Fire OCC continued to task the aircraft when ALL the warnings were there that it wasn’t suitable or safe to task.

Better procedures needed between the fire tasking cell, local weather pilot experts and procedures for dropping in the event of no bird dog….

Really sad and seems / sounds a totally avoidable accident, RIP!

Very sad and many questions. Heavy tankers dropping without bird dog inspections and no actual leading in to the drop run. Tanker B137 drops after the bird dog pilot refused the assignment due forecast conditions and then the drop aircraft B137 reports the conditions as “horrible-don’t send anyone down here”

Then B137 is asked to reload and return. What the hell is going on? The c130, bomber 134 turns up with no lead plane and is diverted to a fire to the East. The conditions would have been no better. Footage indicates the drop went well on the fire edge, with the aircraft turning left. Turbulence, wind sheer, rotor, visibility, sudden loss of airspeed. Who knows.

I wonder about commercial pressure. I wonder why there seemed to be no real coordination with the bird dog and the two drop aircraft. Both aircraft dropped without any lead in aircraft assistance. Is this standard procedure in NSW?

I think the whole system needs a good hard looking into,

Operating these big airtankers is a very different game compared to throwing a couple of AT802’s at a bushfire.

As I said, very sad.

I worked many years in the USAF as an Aircraft Fuel Systems Mechanic. A majority of my time spent on C-130’s. It is unusual for this type of aircraft to crash, even in bad weather conditions. Keep in mind these are the aircraft the USAF Reserves use for hurricane hunters, where they encounter very windy conditions.

My condolences to the families of the experienced crew.

So we still have no definitive reason for the crash or did I miss some thing?

“The interim report does not contain findings nor identify safety issues, which will be contained in the final report.”