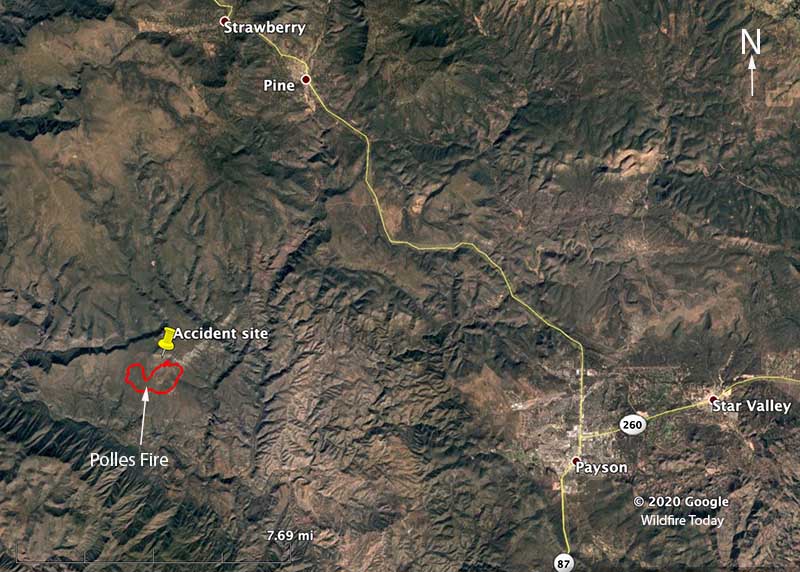

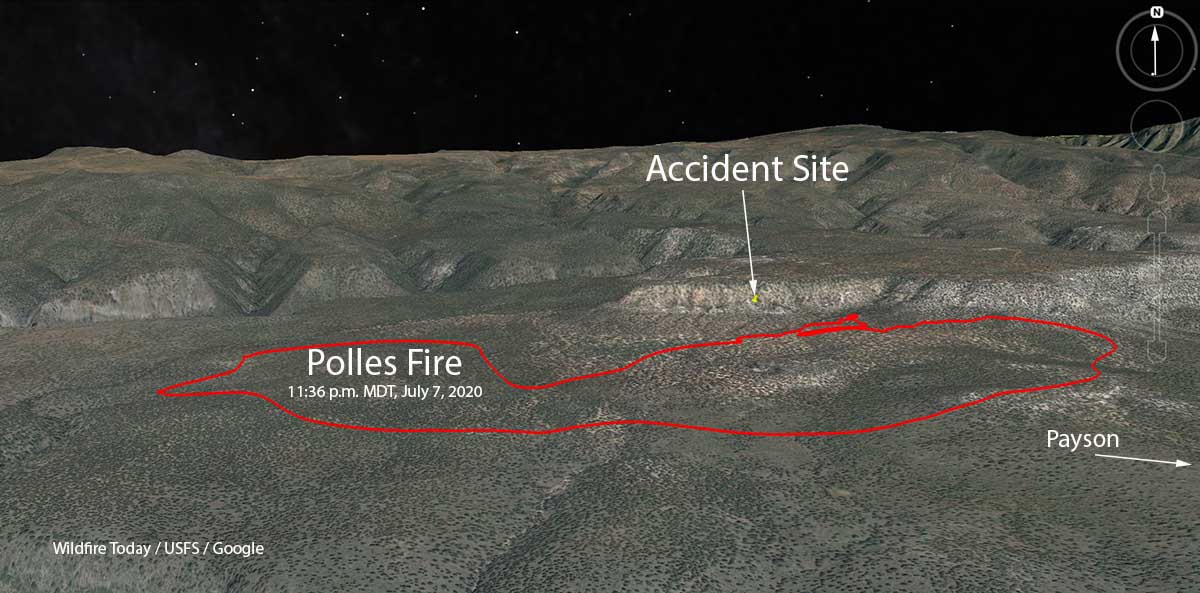

On July 7, 2020 a UH-1H helicopter crashed while transporting supplies to firefighters who were spiked out (camping) while working on the Polles Fire about 10 miles west of Payson, Arizona. The only person on board, pilot Bryan Jeffery “BJ” Boatman, 37, of Litchfield Park, Arizona was killed. We send our sincere condolences to the family and friends of Mr. Boatman, and to the forestry technicians who were at the fire.

The brief preliminary report issued by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) did not mention any obvious causes for the crash, which happened while transporting firefighters’ equipment in an external sling load. Multiple personnel on the ground observed the helicopter flying erratically until finally “it entered a steep nose up attitude and then descended rapidly,” according to the report. Fire personnel saw no signs of fire before the crash and all major structural components of the helicopter were accounted for at the accident site.

BJ was born on June 8, 1983 in Provo, Utah. He was a third-generation pilot and worked alongside his parents to build their company, Airwest Helicopters of Glendale, Arizona.

The helicopter, N623PB, serial number 64-13689, was manufactured in 1964. It is a UH-1H registered to Aero Leasing in Glendale, Arizona, the same city where Air West Helicopters is located.

In addition to the preliminary report released by the NTSB, a 23-page facilitated learning analysis (FLA) was commissioned by the U.S. Forest Service.

The FLA is solely devoted to analyzing the response to the accident — the Incident Within an Incident and the actions taken in the following days. It does not address what caused the helicopter to crash. The report found very little to criticize and praised most of the actions that were taken. It goes into quite a bit of detail about how the fire’s Incident Management Team handled the emergency response during the first few hours, as well as organizing over the next several days to care for BJ’s family and the forestry technicians that were witnesses to the crash or were otherwise affected.

Anyone who could in the future find themselves in a similar unfortunate situation would benefit from reading this FLA. Firefighting is dangerous, in the air and on the ground, and others will have to walk this same path.

During a 49-day period that began July 7, 2020 there were six crashes of firefighting aircraft — three helicopters and three air tankers. In addition, three members of the crew of a C-130 from the U.S. died when their air tanker crashed January 23, 2020 while fighting a bushfire in New South Wales, Australia.

Below is the text from the narrative portion of the three-page NTSB report. The complete report which will analyze the cause, might be released within the next year.

“On July 7, 2020, about 1213 mountain standard time, a Bell/Garlick UH-1H helicopter, N623PB, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Payson, Arizona. The pilot was fatally injured. The helicopter was operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 133 external load flight.

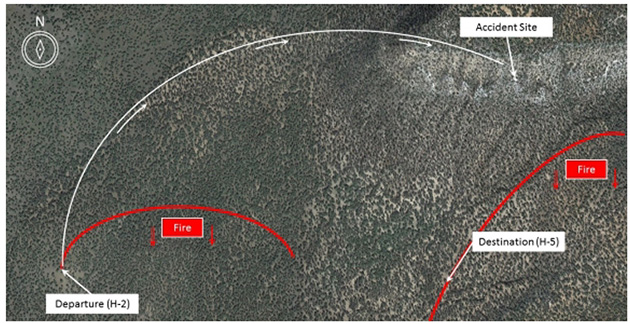

“The helicopter was owned by Airwest Helicopters LLC and operated by the United States Forest Service at the time of the accident. According to witnesses, the helicopter was transporting supplies using a long line for a hotshot firefighting crew that were repositioning on the ground. The pilot transported three loads to the new destination uneventfully prior to the accident and had been using an indirect route to the north to avoid a fire area (Figure 1). While transporting the fourth load, witnesses observed the helicopter begin to fly erratically while en route to its destination. During this time, a witness stated that he observed the helicopter enter a high nose-up pitch attitude and the external payload began to swing. The helicopter then displayed irregular movements for several seconds before the external payload settled and the helicopter appeared to stabilize. However, after about 3 seconds, multiple witnesses observed The witnesses did not observe the helicopter on fire during the accident flight, nor did the pilot report any anomalies over the helicopter crew’s common air-to-ground radio frequency or any other assigned frequencies for the fire.

“The helicopter wreckage came to rest about 0.5 nm north of its drop off destination, oriented on a heading of 074° magnetic and was mostly consumed by postcrash fire. All major structural components of the helicopter were accounted for at the accident site. The helicopter’s external payload was found 123 ft southeast of the main wreckage.

“The wreckage was retained for further examination.”

Greetings Bill,

I hope this well written comment on the tragic fatal helitack crash on the Polles Fire near Payson Az is helpful.

I enjoy forwarding your fire aviation articles to a very good friend of mine here in Taos NM, who works for the US Heli Ski association. He has the very tough job of inspecting the major heli ski operations throughout AK, Canada & the lower forty eight states as well.

Of course, some of these heli ski operations safety track records do not speak well for a clean safe track record, as they have been marred by some poor decision making, usually because of just trying to please cranky anxious clients jonesing to get out & ski in high risk, very unsafe hazardous unstable snow conditions and of course as a result of these mistakes in good guide judgment, there has been some tragedy & loss of lives as a result over the years.

Below here was his professional take on the crash. I’m sure there are many other considerations, he tried bring in to the scope of the discussion here, but obviously he was not totally familiar with this helicopter, nor was he part of the first response incident team.

Just sharing,

-JB

Somehow the most critical sentence in the narrative was cut off. “However, after about 3 seconds, multiple witnesses observed” and it ends there.

My guess is that he had a hydraulic system failure. That would account for the erratic flying, which momentarily resolved, followed by a steep upward pitch before the crash. I am not familiar with the mechanical systems on UH-1’s. More modern helicopters have completely redundant hydraulic systems, but I don’t think civilian helicopter of that vintage (1964) would have had a redundant system.

The three great vulnerabilities of single engine helicopters are: 1. Tail rotor (anti-torque) failure; 2. Gear box failure; 3. Hydraulic system failure. Notice that engine failure is not listed. If your engine fails, provided you have sufficient altitude and/or speed, you auto-rotate to a hard, but survivable landing. If you have problem #1, the helicopter spins wildly and is uncontrollable. The witnesses didn’t describe that. If you have #2, you lose power transfer from the engine to the main and rear rotors. It is difficult to impossible for a pilot to control that, but the helicopter usually drops out of the air or “glides” in at a steep angle. Helicopters are controlled by their hydraulic systems – a pump that runs off the gear box which manages the pitch angle of the blades of the main rotor (and the tail rotor blades) as they rotate. If the system fails, the pilot cannot control the pitch angle or bank angle of the helicopter.

Not to second guess the pilot – 20:20 hindsight – but sling loads are always jetisonable at the touch of a button on the collective control stick. If the pilot had jettisoned the sling load as soon as he realized that he had a problem, he might have been able to put the helicopter on the ground safely. Notice I didn’t say “got back to base safely.” If you have a possible hydraulic system failure, you put it down anywhere you can, as soon as possible.