Climate change and land-use change are projected to make wildfires more frequent and intense, with a global increase of extreme fires of up to 14 percent by 2030, 30 percent by the end of 2050, and 50 percent by the end of the century, according to a new report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and GRID-Arendal.

The study calls for a radical change in government spending on wildfires, shifting their investments from reaction and response to prevention and preparedness.

In the report, wildfire is defined as “an unusual or extraordinary free-burning vegetation fire which may be started maliciously, accidently, or through natural means, that negatively influences social, economic, or environmental values”.

The study, Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires (117 MB), finds an elevated risk even for the Arctic and other regions previously unaffected by wildfires in recent centuries. The publication calls on governments to adopt a new “Fire Ready Formula”, with two-thirds of spending devoted to planning, prevention, preparedness, and recovery, with one third left for response. Currently, direct responses to wildfires typically receive over half of related expenditures, while planning receives less than one per cent.

To prevent fires, the authors call for a combination of data and science-based monitoring systems with indigenous knowledge and for a stronger regional and international cooperation.

“Current government responses to wildfires are often putting money in the wrong place. Those emergency service workers and firefighters on the frontlines who are risking their lives to fight forest wildfires need to be supported”, said Inger Andersen, UNEP Executive Director. “We have to minimize the risk of extreme wildfires by being better prepared: invest more in fire risk reduction, work with local communities, and strengthen global commitment to fight climate change”.

Wildfires disproportionately affect the world’s poorest nations. With an impact that extends for days, weeks and even years after the flames subside:

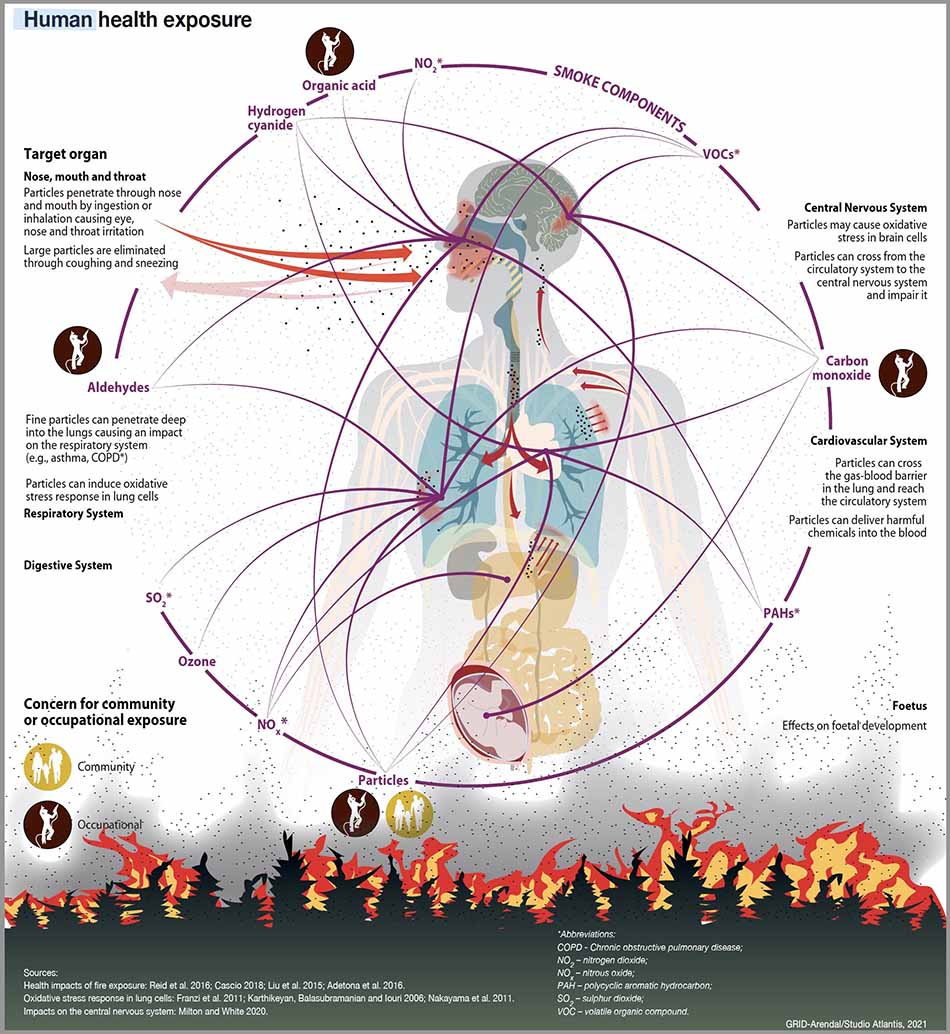

· People’s health is directly affected by inhaling wildfire smoke, causing respiratory and cardiovascular impacts and increased health effects for the most vulnerable;

· The economic costs of rebuilding after areas are struck by wildfires can be beyond the means of low-income countries;

· Watersheds are degraded by wildfires’ pollutants; they also can lead to soil erosion causing more problems for waterways;

· Wastes left behind are often highly contaminated and require appropriate disposal.

Wildfires and climate change are mutually exacerbating. Wildfires are made worse by climate change through increased drought, high air temperatures, low relative humidity, lightning, and strong winds, which causes hotter, drier, and longer fire seasons. At the same time, climate change is made worse by wildfires, mostly by ravaging sensitive and carbon-rich ecosystems like peatlands and rainforests. This turns landscapes into tinderboxes, making it harder to halt rising temperatures.

Wildlife and its natural habitats are rarely spared from wildfires, pushing some animal and plant species closer to extinction. A recent example is the Australian 2020 bushfires, which are estimated to have wiped out billions of domesticated and wild animals.

The report said the restoration of ecosystems is an important avenue to mitigate the risk of wildfires before they occur and to build back better in their aftermath. Wetlands restoration and the reintroduction of species such as beavers, peatlands restoration, building at a distance from vegetation, and preserving open space buffers are some examples of the essential investments into prevention, preparedness and recovery.

The report concludes with a call for stronger international standards for the safety and health of firefighters and for minimizing the risks that they face before, during and after operations. This includes raising awareness of the risks of smoke inhalation, minimising the potential for life-threatening entrapments, and providing firefighters with access to adequate hydration, nutrition, rest, and recovery between shifts. Women firefighters face various challenges ranging from gender discrimination and sexual harassment to ill-designed equipment and protective clothing that puts them at greater risk of injury.

Smoke associated with deforestation fires in the Brazilian Amazon has been found to be responsible for the premature death of almost 3,000 people annually (95 percent percentile confidence interval: 1,065–4,714), demonstrating the regional scale of fire impacts (Reddington et al. 2015).

Our take

The report predicts a global increase of extreme fires of up to 14 percent by 2030 and 30 percent by the end of 2050. The statistics for the United States from the National Interagency Fire Center since the 1980s indicates that the total acres burned and the average size of wildfires has been far exceeding those rates of increase. The data, which does not include Alaska since those fires are managed far differently from the rest of the US, shows during the forty-year period approximately a 400 percent increase in the average size by decade, and more than a 300 percent growth in the total acres burned each year. The statistics for the US are for all fires, not just those that “negatively influence social, economic, or environmental values.”

Another factor that may influence the size of fires in the US is that some wildfires are not totally suppressed and can be herded around to attempt to protect private land, structures, and certain resources. They may burn for months, and occasionally grow far beyond what was expected. The use of a limited suppression strategy can be to allow fire to be reintroduced to replicate natural conditions and reduce fuels. Or in recent years it could be due to extreme fire activity in the Western US and a shortage of firefighting resources as a result of difficulties in hiring, retention and recruitment.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Rick and Tom.

“Another factor that may influence the size of fires in the US is that some wildfires are not totally suppressed and can be herded around to attempt to protect private land, structures, and certain resources.” And the fact that more focus is being placed on burning out thousands of acres instead of going direct. I get it, and if we’re going to have an increase in large fires, won’t that mean less fuel to burn in the long run?

Not 100% sold, as many fire seasons aren’t as active as some. If the doom and gloomers were right, wouldn’t every season be worse than the last?

Hi Jeff,

Think of it like this – if every 10 years, the average amount of burned area, cost of suppression, houses burned etc. goes up, then you still have a problem even if there is substantial variation in between the years of that decade. Example – the 2019 season was a bummer season to be on a hot shot crew because it was so damn wet all over the west there were hardly any fires and no fires means no OT, obviously. 2016 was also not that great unless you were on the Soberanes or Pioneer as many were. However over the past 10 years the average amount of burned area, suppression costs, houses burned has gone up substantially. So, still a problem even though we have slow years.

Right, and more houses being built in the wui means potential of more being burnt. Some GACCs being more active than others year by year. I still see fire seasons as being very active for a few months out of the year (depending on GACC), with the odd large fire here and there out of season. I was on both fires you mentioned, and in my opinion, both, as with other large fires, got big due to a change in suppression strategy over the years that are contributing to the average size of large fires. Not saying drought doesn’t have a lot to do with it, just that other factors are having an impact also.

Focusing on climate change is not helping the problem. Neither is blaming fuels.

The last several years have seen extreme fire behavior on days the weather and fuel moistures were mild and well within what was historically considered moderate. We have also seen extreme fire behavior in light fuels, recent burns, and areas that have been managed for fire resistance.

So there is either some not well understood synergistic effect going on, or there is another unknown/unaddressed factor in fire behavior.

Are you leaving some things out, dead vs live fuel moisture, fuel size (1 hour vs 1000 hours), invasive grasses and forbs, long term drought? As fire managers if we have only learned one thing in our career it is fire/fuels is complicated and hard to predict regardless of weather. All we can do is our best.

Can we all agree agencies managing wildland fire need more money? Our employees deserve better pay, health care, retirement, work life balance, etc.

“Fire science is not rocket science — it’s way more complicated.”

That quote comes from research ecologist Matt Dickinson of the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station who said he borrowed it from a colleague.

100% correct Sharon. I remember in the 70’s that all the climate experts said we were entering an ice age. Once the meteorologists start hitting 70 or 80% in their predictions, then I might start putting faith in long range guesstimates. Otherwise, I see these sorts of reports as folks making making money off government grants to “study” things.

“Another factor that may influence the size of fires in the US is that some wildfires are not totally suppressed and can be herded around to attempt to protect private land, structures, and certain resources. They may burn for months, and occasionally grow far beyond what was expected. The use of a limited suppression strategy can be to allow fire to be reintroduced to replicate natural conditions and reduce fuels. Or in recent years it could be due to extreme fire activity in the Western US and a shortage of firefighting resources as a result of difficulties in hiring, retention and recruitment.”

Yes, you cannot make predictions about future things without incorporating how they are working today and whether those policy/resource conditions are likely to change or not in the future. Well, I guess you can make predictions but they’re not very meaningful. IMHO.