1:59 p.m. MST Nov. 18, 2021

This article was first published at Fire Aviation.

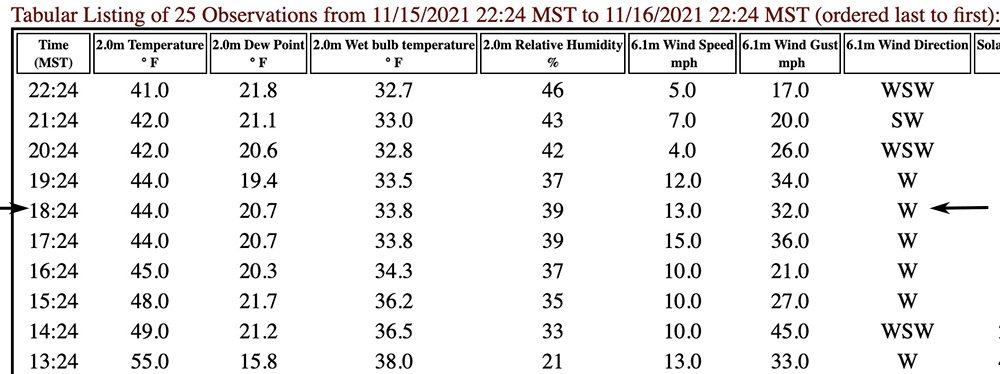

Around the time Single Engine Air Tanker 860 crashed at the Kruger Rock Fire in Colorado at approximately 6:36 p.m. MST on November 16, killing pilot Marc Thor Olson, the Estes Park ESPC2 Remote Automatic Weather Station recorded sustained winds of 13 mph gusting to 32 mph out of the west. The station is 3.7 miles northwest of the fire at 7,892 feet and its anemometer is 20 feet above the ground.

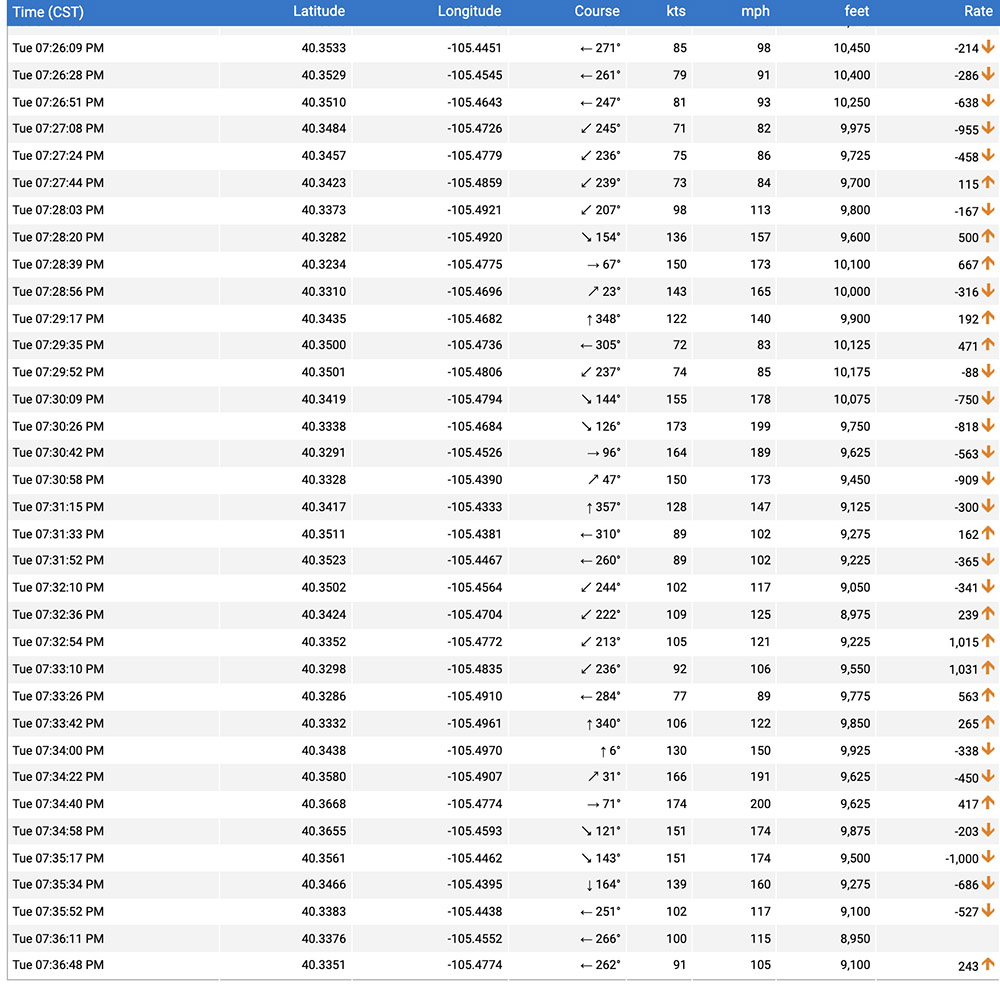

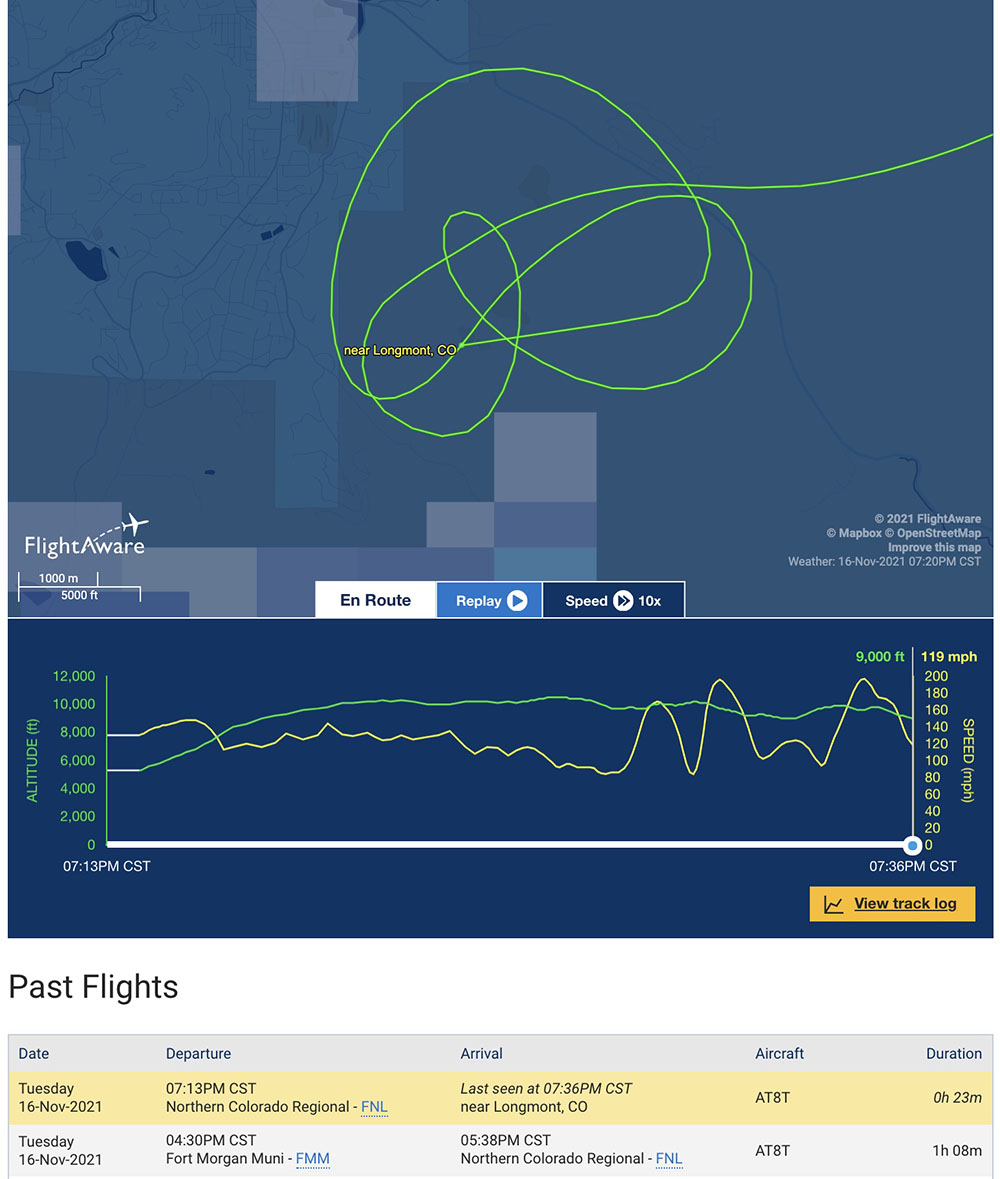

Looking at the flight tracking log from FlightAware above, the wind appeared to be much stronger at the plane’s altitude, which was 8,950 to 10,450 feet while it was over the fire. The highest peak just south of the fire is at 9,400 feet.

As it made four orbits near the fire during the 10 minutes it was in the area, the ground speed of T-860, an Air Tractor 802A (N802NZ) varied from a low of 82 mph while flying west to a maximum of 200 mph when east-bound. These shifts in ground speed were consistent during all four orbits. This indicates a very strong wind out of the west, a direction that is consistent with the data from the weather station.

There are two reasons that fixed wing air tankers avoid attacking wildfires during strong winds. One, the wind makes it difficult or impossible for the retardant to hit the target, getting blown horizontally as it falls from the aircraft to the ground. Second, flying low and slow, as air tankers have to do, is difficult in mountainous terrain with calm winds, but it can be extremely hazardous during strong winds.

When you add a third complexity of dropping at night using night vision goggles, something that has been done very little in the history of aviation, and never before in Colorado, the pilot had the deck stacked against him. The chances of stopping or slowing the spread of the fire with retardant, water, or any other suppresant, were very, very slim. (There is a report that the operator of the aircraft, CO Fire Aviation, experimented with night drops in Oregon in 2020 and 2021.)

NEW: CO Fire Aviation confirms the pilot killed in the air tanker crash last night was Marc Thor Olson. He told me most people called him Thor.

This is a picture I took of him last night as he was prepping his plane. The crash happened about an hour later #9News pic.twitter.com/uEOO4tbXwK

— Marc Sallinger (@MarcSallinger) November 17, 2021

The weather forecast available from the National Weather Service that Tuesday afternoon called for continued very strong winds until sundown and a chance for snow Tuesday night. It predicted dry weather on Wednesday and Thursday with high temperatures in the 30s and 40s under mostly sunny skies with the relative humidity around 20 percent. The wind chill was expected to be below zero from Wednesday afternoon until Thursday afternoon. The actual low temperature Tuesday night turned out to be 11 degrees.

Risk vs. reward

With 20/20 hindsight looking at risk vs. reward, this was a very high risk mission. The potential reward was little, considering the likely effectiveness of 700 gallons of suppressant blown off target by strong winds and the weather forecast of a chance of snow in a matter of hours and wind chills the next day below zero.

Who decided to attempt the night flight?

The short answer is, the Larimer County Sheriff’s office ordered the aircraft to respond to the fire, using a “verbal call when needed contract”, an arrangement that was first agreed to on October 5, 2021.

A preliminary map appears to show that the fire was just inside the boundary of the Roosevelt National Forest. The Larimer County Sheriff’s office said on Wednesday Nov. 17 that as of 7 a.m. that day the fire was being managed by a unified command with the US Forest Service and the Sheriff.

In Colorado, Texas, and Wyoming the local county sheriffs are given the responsibility for suppressing wildfires outside of cities unless they are on federal land. The Kruger Rock Fire was in Larimer County.

As Wildfire Today reported November 16, before the fatal flight, T-860 departed from the Fort Morgan, Colorado airport, orbited the fire about half a dozen times, then landed at Northern Colorado Regional Airport at 4:38 p.m. MST. This flight is listed in the image from FlightAware above as one of two flights that day for the aircraft. It turns out that on the first flight it dropped water on the fire, which the pilot reportedly described as “successful”. After it landed at Northern Colorado Regional Airport it reloaded with “fire suppressant” instead of water, and by 6:13 p.m. MST was airborne returning to the fire.

Sunset that day was at 4:44 p.m. MST. The air tanker disappeared from tracking at 6:35 p.m., about 1 hour and 49 minutes after sunset. Air tankers working for the U.S. federal government are allowed to drop only as late as 30 minutes after official sunset.

The Denver Post reported that CO Fire Aviation said in a statement, “There was no aerial supervision or lead plane required for the mission and weather and wind conditions were reported to be within limits of our company standard operating procedures.”

In the video below Juan Browne has strong feelings about this incident. Shortly after posting it, he wrote a comment saying, “GROUNDSPEED NOT AIRSPEED!”

Below is an excerpt from a statement released November 17, 2021 by the Larimer County Sheriff’s office:

“On the morning of November 16, 2021, the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office and many partner agencies responded to and began fighting the Kruger Rock Fire southeast of Estes Park. The terrain where most of the fire was burning made it too dangerous to insert firefighters to battle the fire directly. The gusty winds, higher than normal temperatures, and low relative humidity suggested great potential for the fire to grow quickly. Incident Command knew the best chance of getting ahead of the fire was with the use of air drops from aviation resources.

“Around midday, LCSO reached out to CO Fire Aviation (Fort Morgan, CO) and asked if they would be able to assist with air operations. CO Fire Aviation said they were available, had a plane, a pilot, and were interested in assisting. They also discussed the fire and weather behavior as LCSO wanted to make sure CO Fire Aviation was aware of and comfortable with the conditions.

“A few hours later, CO Fire Aviation said they were checking the weather and crosswinds at the fire and were comfortable making air drops. The plane left Fort Morgan and headed to the fire with a load of water. With LCSO resources on the ground communicating with the pilot, the water drop was successful. The pilot reported the wind was not too bad at the fire and said he would head to Loveland to get a load of suppressant to make a second drop.

“About an hour later, the plane returned to the fire and the pilot told ground resources it was turbulent over the fire, conditions were not ideal to make a drop, and that he was going to make one more pass and then return to Loveland. Moments later, at approximately 6:37 p.m., ground resources heard the plane crash.

“LCSO’s relationship with CO Fire Aviation began earlier this year when CO Fire Aviation invited LCSO, several fire departments, and other counties to a demonstration they had planned in Loveland. LCSO representatives attended the demonstration and were interested in the services CO Fire Aviation were offering, including night air operations.

“In recent years, we have experienced the severe fire behavior in Colorado as demonstrated by the 2020 Cameron Peak Fire. Recent advances in technology to achieve night air operations already in use in other states has proven to be an effective tactic to help prevent medium-sized fires from exploding and making large runs like we saw last year.

“LCSO also knew that air resources are often stretched thin and sometimes not available when needed. After the Loveland demonstration, LCSO continued talks with CO Fire Aviation to learn more about their services, response times, costs, etc. CO Fire Aviation offered the capability and LCSO was willing to give them the opportunity if it would benefit firefighting operations.

“LCSO entered into a verbal “call when needed” contract with CO Fire Aviation on October 5, 2021 in lieu of an exclusive use contract. A written contract is still being negotiated. LCSO had reached out to CO Fire Aviation about their services during other fires this year, but they either did not have the availability, or it was decided air operations were not needed on those fires. The Kruger Rock Fire is the first time LCSO used the services of CO Fire Aviation.”

We should all look up the Webster definition of “dispatch”.

Thank you Martha. What was (or were) the Dispatch office(s) on the fire? USFS Dispatch? Larimer County Dispatch? The Sheriff’s cell phone? If multiple dispatch offices, were all offices made aware of this flight?

Verbal contracts and SEATs do not have a good track record: https://apps.usfa.fema.gov/firefighter-fatalities/fatalityData/detail?fatalityId=714

But we, as fire managers, should have the knowledge and experience to make the sound decisions based on risk management, and only when there is a high probability of success. Risk vs Reward.

The pilot always has the final GO/NO GO decision.

Hi Bill,

I buy old, cheap books because of their titles.. I had no idea, when I bought the book with the title “wind, sand and stars”, what it was about. It was published in 1939 and its author was antoine de saint-exupery written in the French language and translated to English by Lewis Galantiere. This book is not known for its scientific importance; but only for its literary significance.

However, Antoine was a French aviator and in chapter titled ‘Elements’ he attempted to describe his experience of flying in clear sky atmospheric turbulence whose peak gusts were 150 mph and his plane was stationary 5 miles off the coast of Argentina at about 45 degrees south latitude.

I believe Antoine’s experience of ‘Elements’ is very much related to what caused Olson’s plane to crash. Which likely has little to do with the influence of a 100 acre (or so) wildfire or flying at night. I am confident the crash was the result of clear air turbulence caused that the unique terrain and location of the fire and the not well understood phenomenon of CLEAR AIR TURBULENCE. So, I urge you to inform the authorities investigating Olson’s crash about Antoine’s experiences with this phenomenon which occurred before 1939. And I urge you to urge these authorities to email me (you have my email address to share with them) so I might question them to see if they have SEEN everything that I have SEEN relative to what you have reported and what Antoine reported about his experiences of more then 80 years ago.

Have a good day, Jerry.

Jerry, Clear Air Turbulence is sometimes associated with mountain wave activity, which can occur hundreds of miles downwind of terrain, but mostly is associated with the jet stream; this type of turbulence is a high-altitude hazard.

Turbulence at low altitudes is entirely different, and it’s for that reason that the limitation of 30 knots was established over the fire, for SEAT operations. More importantly, the wind speed is affected by terrain. Wind passing between peaks or through a canyon can be accelerated to much higher velocities, similar to the way water squirts when one puts a thumb over the end of a garden hose. This is the venturi effect, and a 30 knot sustained wind can easily be 50-60 mph or higher when passing through a constriction in the terrain.

Additionally, wind spills over mountains and around terrain much the same way that water flows over rocks in a river. Think of the whitewater rapids as illustrating the way water rolls, tumbles, and forms local air currents. On the back side of a ridge (the “lee side”), downdrafts form which can exceed the flight performance of an airplane. Strong “rotors” also form, which can be envisioned as air rotating or rolling like a giant hair curler. This impacts aircraft’s controllability.

Turbulence close to terrain can become not just rough, but violent, and frequently is, over a fire. Aircraft orbiting above the fire may experience just a small amount of the turbulence that an aircraft may experience when descending or approaching a drop. Large air tankers descent to 400′ above the canopy, and SEATs to 60′. This affects controllability, it also affects the workload, which involves not only keeping the airplane under control, but putting it where it needs to be to get the retardant where it needs to be, while accounting for terrain, personnel on the ground, an escape route, etc. This is further tempered by restrictions to visibility such as smoke, terrain, lighting, and so on.

I have seen many occasions when the turbulence is severe to extreme, when one cannot necessarily read one’s instruments, because it is too rough. In a SEAT, the stick is in constant motion on a drop, as may be the rudder pedals. Every drop is planned with an exit or escape carrying the full load, a conservative rule that takes into account the potential inability to drop. The 802, like most aircraft, is a great performer empty, and performance-limited at gross weight. When exiting a drop, or if one puts one’s self into a position requiring performance to exit, that performance can be reduced or limited by downdrafts, wake turbulence, density altitude, and other factors.

Saint-Exupery was one of the great aviation writers (and a figure in aviation history), and his writing is poetic and classic. The same turbulence he experienced is still there today, and the same factors and influences still cause it, as they do over the fire, and it still presents the same challenges and limitations.

The only authority with the decision to go to that fire, indeed the only person entitled and able to make the decision to go to the fire, is the pilot. There is no authority in the United States, including that of the office of the President of the United States, that exceeds that of the pilot in the cockpit, and he, and he alone, makes the decision to accept a dispatch.

A dispatch is nothing more than a request.

Presently, we do not know why the aircraft crashed, whether it was medical, mechanical, environmental, spatial disorientation, or other causes. The rush to speculation is best left until facts have emerged as to the cause, and energy better spent presently remembering the pilot who lost his life. Ultimately he believed in his decision enough to bet his life on it. When dispatched to a fire, if we elect to go, we all make that same choice. It would be best to wait for facts in evidence, before placing blame.

Pilots are gonna fly. It’s up to Managers, Safety Officers and others to go through and decide if this flight is worth it.

Every firefighter or pilot wants to do what they are trained to do, but it’s up to managers how best to deploy your resources.

Exactly

You may want to brush up on page 46 of the IRPG

https://www.nwcg.gov/publications/461

You may want to brush up on Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 91:

14 CFR 91.3(a):

§ 91.3 Responsibility and authority of the pilot in command.

(a) The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-91/subpart-A/section-91.3

In exercising that authority, the pilot takes into account airworthiness, his own physical condition, rest, health, mechanical state, wind, weather, runway length, temperature, weight, takeoff distance, climb gradient, fuel burn and duration, fire conditions, distance, altitude, traffic, and many other factors. Much of the time, the pilot does not know the nature of the fire, or necessarily the reason for the dispatch, or the particulars.

Over the years, we have seen an increasing trend toward fires in worse visibility, higher winds sometimes worse weather. After the C-130 was lost in a microburst several years ago, that same season and every year thereafter, I was called into fires with microburst activity on scene, frequently with a leadplane on site who said don’t worry about it. In fact, that’s what I was told as I approached Yarnell several years ago, with large, very active thunderstorm activity approaching. We see it, we’re monitoring it, we’re not concerned. When I noted there would be a wind shift and a big change in fire direction and behavior, I was told not to worry about it, they had it in hand. Just after that, the fire blew up, changed direction and ran down the Granite Hot Shots, with whom I’d worked only a few minutes before.

That said, fire is dynamic, and frankly, if we thought we were enjoying our last few minutes on earth at any given time, we certainly wouldn’t go do something. We do it because we have different expectations of the outcome. I guarantee that Mr. Olson didn’t undertake his last mission with the expectation that it would be his last. None of us do.

SEATs have a 30 knot wind limitation over the fire which has been in place for a number of years. 30 knots over flat ground is very different than 30 knots in steep, rough mountainous terrain.

The 802 is not an instrument platform, certainly not compared to a Twin Commander or a King Air. It lacks the same degree of instrumentation. It’s not nearly as stable. It takes both hands to actively fly, and in wind and turbulence, one is busy. That said, the 802 is in use in some challenging environments, including those that utilize night vision equipment. A number of those flying 802’s on fire contracts have experience, some of it extensive, spraying at low altitude at night, and there are a number of those involved in SEAT operations today with experience operating 802s in challenging places such as Colombia and Yemen. You may or may not understand the significance of this, and how this experience may apply, and it need not be explained.

Mr. Olson was not inexperienced.

Numerous entities may request an air tanker. Making a request not impose a requirement to respond or take the dispatch. The person making the request does not and cannot presume to decide for the pilot. No person in the government or the civil world has the authority to do so. It’s strictly the pilot’s call. Any number of participants can stop the show, but the ultimate responsibility for going to the fire, and for the outcome, rests in all cases, without exception, with the pilot in command.

Your statement that “Pilots are gonna fly” is wrong, and offensive. We are neither automatons nor drones slathering to take any dispatch without consideration of all the information available to us. We are professionals. We make calls based on numerous elements, but above all, on our judgement. Our decisions are not always correct, and on occasion, we do pay a high price. Your statement does not suggest you are a pilot who flies fires, but you seem to think that those who do are unable to help themselves, and will do anything requested, or that they’re told to do. This is untrue.

We are a can-do organization, peopled by can-do people. That doesn’t mean the answer is always “yes,” and in fact is not uncommonly, “no.” I’ve refused to go to fires, and I’ve arrived on scene and determined I could not do what was asked. In most cases, I try to offer an alternate solution: I can’t do that, but I can do this.

Innovations and change and evolution in the industry occurs. This flight, it was the first introduction of night vision. Those who say that a SEAT shouldn’t have been sent to the fire when it could only carry 700-800 gallons may be missing the point. Mr. Olson noted earlier in the day that this flight, or the use of NVG’s over a fire, has been five years in the development.

Presently we do not know why this mishap occurred. This event may or may not have had anything to do with night conditions, or wind, or the use of night vision equipment. We don’t know. It may be best to know that before pontificating on the failures, errors, and laying blame.

Justin Smith should resign. Get the Sheriff’s out of wildfire in Colorado. It’s 2021 not 1911.

Doug, just a comment about what you mentioned with the wind limitation for a SEAT. While that might be the maximum sustained winds, I believe, having flown on and managed many aviation missions in the Estes Valley, that the gust spread was more of a factor in this case. It was interesting to read the eyewitness account of the photographer who was nearby. As he described it, about the same time as the crash, he got hit with what he called a rogue gust of wind that almost blew him over. I was in a Hiller Soloy counting elk over Estes about 5 miles from where this crash occurred, when we got hit by such a gust that literally almost pile drove up into the ground. Only a few hundred feet off the deck did the pilot regain control. I totally agree with you that all is speculation until the NTSB issues their report. But I can tell you the winds around Estes are a special kind of vicious, especially with a loaded aircraft that as you say, is fairly unstable and take two hands to fly.

I would sue the hell out of whatever agency was in charge, whatever IC ordered the flight, and whatever agency operated the contract. Hell, they should be seeking criminal negligence charges.

There is no way you could be a responsible party and think that flying a SEAT at night would buy you any meaningful tactical advantage on that fire. This goes in the top 2-3 dumbest things I’ve ever heard of on a wildfire.

I’m just dumbfounded and shocked at how anyone could climb the ranks to have that responsibility and make that decision.

Bingo. The winds. Risk vs Reward. I have been teaching aviation safety and managing fire aviation operations for over 25 years for the feds. We teach and emphasize recognizing unreasonable risk, and to not assume them and put yourself and others in jeopardy. Unfortunately in this case, the holes in the Swiss cheese model lined up for tragedy. Although the pilot has ultimate say about whether he accepts a mission, we have to look at other factor such as the company’s culture towards safety and whether they became too mission focused and tunneled in on achieving a “first” in fixed-wing air tanker operations. And we need to look at the level of fire aviation training and experience in the Larimer Sheriff’s program. All three levels could have pulled the plug on the mission if they had recognized the extreme flight environment caused by the winds. Anyone who’s flown or manged aviation operations in the Estes Valley will tell you it is one of the most challenging flight environments in the lower 48, even on a good day in the summer.