(UPDATED at 11:35 a.m. PST, December 19, 2013)

An update from the Pfeiffer Fire Incident Management Team (IMT) at about 11 a.m. today revised the size to 917 acres and the containment to 79 percent. The evacuations of the Pfeiffer Ridge Road area remain in effect and the number of destroyed homes is still at 22. More information from the IMT:

Crews made good progress overnight in mopping up and strengthening lines in all areas of the fire. Structure protection continued as well. The expected strong winds which accompanied the cold front moved over the fire at approximately 10:00 pm. The stronger winds created a risk to firefighters from falling trees so crews were pulled off the lines to safety points and the fire was in a monitoring status for the remainder of the shift. Scattered rain occurred over the fire area.

Maps of the fire can be found at the IMT’s Dropbox account. In an interesting twist, California Interagency Incident Management Team 7 did not place any maps on InciWeb, but instead posted an image of a QR code which when scanned with a barcode app on a smart phone will take you to Dropbox. If you viewed Inciweb with a computer or a smart phone, you would not have access to the maps, since neither the smart phone or a computer can scan an image on its own screen. You would have to view the QR code on one device and scan it with a second device. QR codes of map locations on the internet can be useful when printed on an Incident Action Plan handed out to firefighters, but an image of one on an internet site is difficult or impossible to use.

****

(UPDATED at 10:00 a.m. PST, December 18, 2013)

According to the Forest Service, the Pfeiffer Fire on the California coast at Big Sur is now being called 50 percent contained after burning 850 acres and destroying 22 structures, including 14 homes along Pfeiffer Ridge Road. Firefighters were able to save 24 other structures directly threatened by fire. The Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade reports that although her home was lost in the early hours of the fire, their Fire Chief Martha Karstens remains dedicated to the Big Sur community by staying on-duty managing fire brigade resources and responding to emergency incidents.

They are expecting complete containment at 6 p.m. on Friday, December 20.

Evacuations of the Pfeiffer Ridge Road area remain in effect.

Air tankers have been grounded for portions of the last two days due to smoke causing visibility problems. However nine helicopters have been dropping water on the fire. Other resources assigned to the fire include:

- 20 crews

- 46 engines

- 2 dozers

- 4 water tenders, and

- 879 personnel

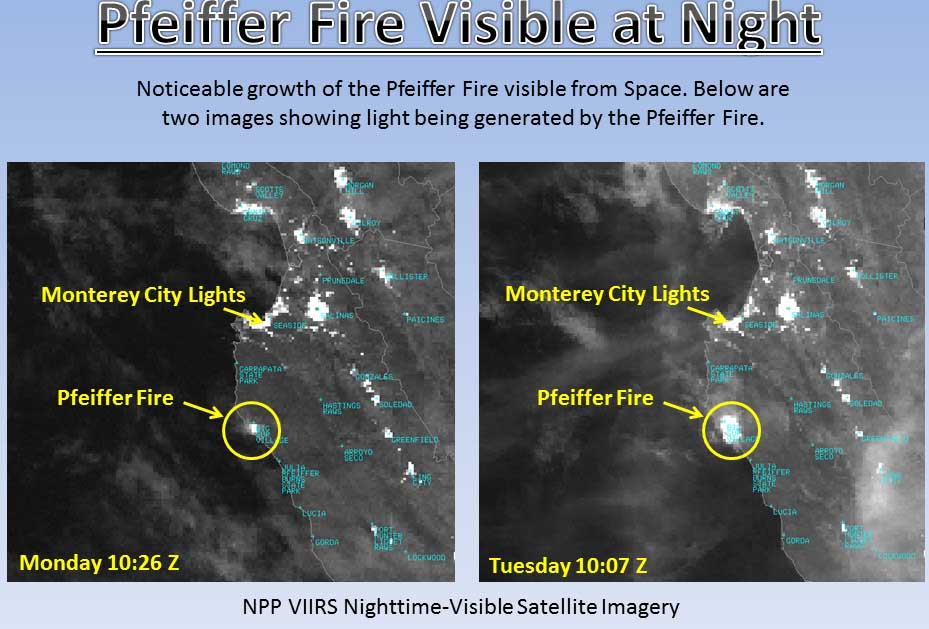

NASA satellite captured an image of smoke from the wildfire near Big Sur, Calif. http://t.co/nHJhyi7nt0 #PfeifferFire pic.twitter.com/X2k8qQHE6d

— NBC Bay Area (@nbcbayarea) December 18, 2013

****

(UPDATED at 5:50 p.m. PST, December 17, 2013)

#Pfeifferfire: Big Sur blaze burns 769 acres, 20 percent contained (updated, photos) http://t.co/ed4n4BchMO pic.twitter.com/z6qy3AVT68

— 89.3 KPCC (@KPCC) December 18, 2013

The Los Padres National Forest reports that the fire is 20 percent contained and has blackened 769 acres — 22 structures have burned. Full containment is expected Friday evening.

****

(UPDATED at 3:12 p.m. PST, December 17, 2013)

A community meeting for the residents of Big Sur will be held this afternoon December 17 at 4:00 pm at the Big Sur Station, Highway 1, Big Sur, CA.

An update from the U.S. Forest Service puts the fire at 500 acres and 5 percent contained. However, heavy smoke and rough terrain make mapping the fire difficult. The fire behavior has been described as running, with spot fires igniting up to 1/4 mile ahead.

The 495 people assigned to the fire include 18 hand crews, 44 engines, 2 dozers, and 3 water tenders.

****

(UPDATED at 10:20 a.m. PST, December 17, 2013)

The cause of the Pfeiffer Fire at Big Sur, California that started between Pfeiffer Ridge and Sycamore Canyon has not been determined. The Associated Press is quoting a U.S. Forest Service spokesperson as saying Tuesday morning it has burned about 550 acres and is 5 percent contained.

The Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade reported Monday afternoon that 15 to 20 homes had burned but that due to heavy smoke in the area it was difficult to determine the exact numbers. The fire is west of Highway 1, which is still open.

The map of the Pfeiffer Fire above depicts the approximate location of the fire based on data from a satellite which can detect heat.

The U.S. Forest Service is still responsible for suppression of the fire and has assigned 625 firefighters who were working under the direction of Curt Schwarm’s Incident Management Team. But at 6 a.m. Tuesday a Type 2 IMT will assume command, with Incident Commander Mark Nunez.

The weather forecast is more favorable for firefighters today, calling for much higher humidities of 30 to 35 percent, mostly sunny skies, and moderate winds. The wind should be 3 to 7 mph, but the direction could be quite variable, again providing a challenge for fire personnel.

At 9:04 a.m. today a nearby weather station recorded 66 degrees, 24 percent relative humidity, and a south-southeast wind of 2 mph gusting to 7 mph.

Continue reading “Fire at Big Sur burns homes, forces evacuations”