By Kelsey Fitzgerald

Wildfire smoke may greatly increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, according to new research from the Center for Genomic Medicine at the Desert Research Institute (DRI), Washoe County Health District (WCHD), and Renown Health (Renown) in Reno, Nevada.

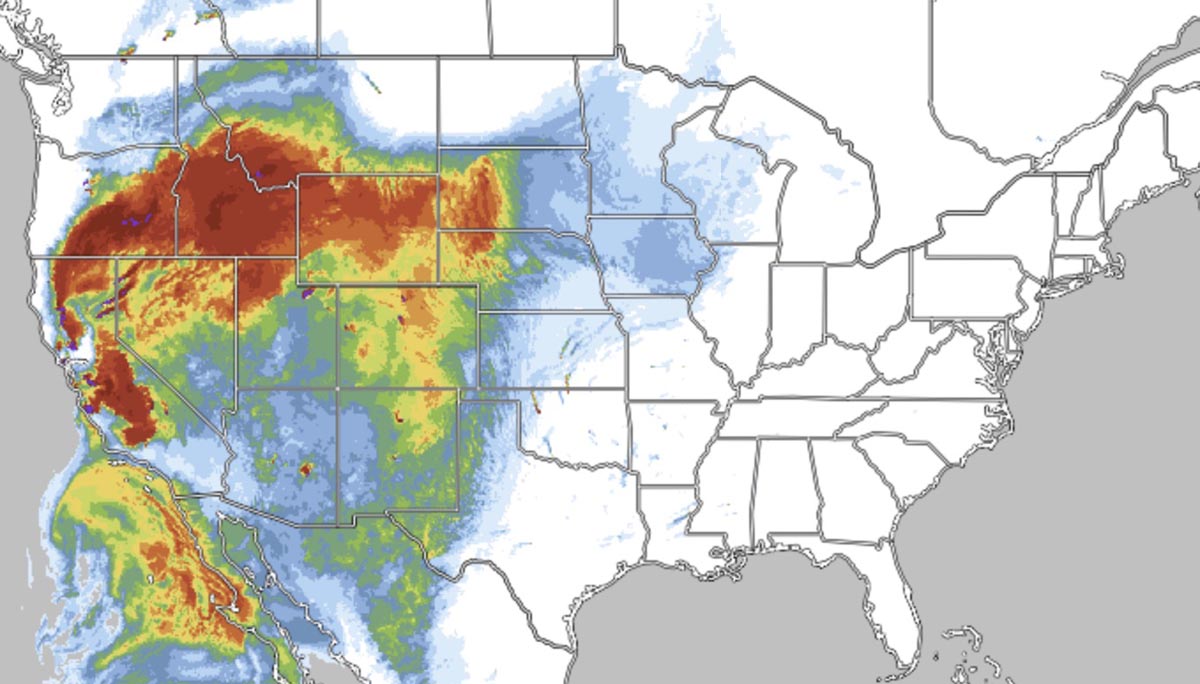

In a study published earlier this week in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, the DRI-led research team set out to examine whether smoke from 2020 wildfires in the Western U.S. was associated with an increase in SARS-CoV-2 infections in Reno.

To explore this, the study team used models to analyze the relationship between fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) from wildfire smoke and SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate data from Renown Health, a large, integrated healthcare network serving Nevada, Lake Tahoe, and northeast California. According to their results, PM 2.5 from wildfire smoke was responsible for a 17.7 percent increase in the number of COVID-19 cases that occurred during a period of prolonged smoke that took place between Aug. 16 and Oct. 10, 2020.

“Our results showed a substantial increase in the COVID-19 positivity rate in Reno during a time when we were affected by heavy wildfire smoke from California wildfires,” said Daniel Kiser, M.S., co-lead author of the study and assistant research scientist of data science at DRI. “This is important to be aware of as we are already confronting heavy wildfire smoke from the Beckwourth Complex fire and with COVID-19 cases again rising in Nevada and other parts of the Western U.S.”

Reno, located in Washoe County (population 450,000) of northern Nevada, was exposed to higher concentrations of PM2.5 for longer periods of time in 2020 than other nearby metropolitan areas, including San Francisco. Reno experienced 43 days of elevated PM2.5 during the study period, as opposed to 26 days in the San Francisco Bay Area.

“We had a unique situation here in Reno last year where we were exposed to wildfire smoke more often than many other areas, including the Bay Area,” said Gai Elhanan, M.D., co-lead author of the study and associate research scientist of computer science at DRI. “We are located in an intermountain valley that restricts the dispersion of pollutants and possibly increases the magnitude of exposure, which makes it even more important for us to understand smoke impacts on human health.”

Kiser’s and Elhanan’s new research builds upon past work of studies in San Francisco and Orange County by controlling for additional variables such as the general prevalence of the virus, air temperature, and the number of tests administered, in a location that was heavily impacted by wildfire smoke.

“We believe that our study greatly strengthens the evidence that wildfire smoke can enhance the spread of SARS-CoV-2,” said Elhanan. “We would love public health officials across the U.S. to be a lot more aware of this because there are things we can do in terms of public preparedness in the community to allow people to escape smoke during wildfire events.”

More information:

Additional study authors include William Metcalf (DRI), Brendan Schnieder (WCHD), and Joseph Grzymski, a corresponding author (DRI/Renown). This research was funded by Renown Health and the Nevada Governor’s Office of Economic Development Coronavirus Relief Fund.

The full text of the study, “SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate in Reno, Nevada: association with PM2.5 during the 2020 wildfire smoke events in the western United States,” is available from the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41370-021-00366-w