University of Maryland (UMD) Associate Professor Michael Gollner will co-lead a first-of-its-kind research effort to quantify the pulmonary and cardiovascular health consequences to firefighters exposed to wildland fire smoke. The research is supported by a $1.5 million award from the Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program administered through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), a Department of Homeland Security agency.

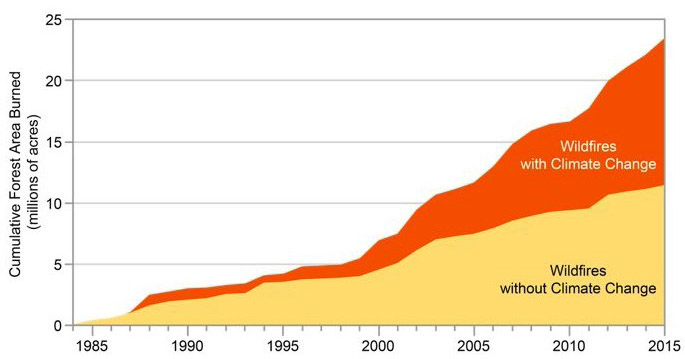

The smoke of wildland fires—such as California’s Mendocino Complex of Fires, which burned 459,123 acres, destroyed 280 structures (including 157 residences), and killed a firefighter during the 2018 wildfire season—contains particulate matter, carbon monoxide, volatile organic carbon compounds, and other toxic hazards that could put firefighters at risk for chronic illnesses such as ischemic heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis).

But unlike structural firefighters who have relatively well-defined respiratory personal protective equipment standards for fighting fires in and near buildings, wildland firefighters have no standards or requirements for prescriptive respiratory protection. And because wildland firefighters are often deployed to a fire for weeks at a time with sometimes repeated deployments for several months over a summer, they experience an exposure pattern with unknown health risks.

“We put wildland firefighters in harm’s way to protect the natural environment, homes and property, and lives. The focus on firefighter safety has largely been about physical injuries such as burns—but as you can imagine, these firefighters are also exposed to a great deal of smoke,” explains Gollner, a fire protection engineer in UMD’s A. James Clark School of Engineering. “We know there can be health consequences to this, but we have no data on the long-term effect of wildland fire emissions on the heart, blood vessels, and lungs of front-line wildfire responders, because it’s incredibly difficult to study.”

The FEMA-funded research will look at different smoke exposures that mimic both smaller prescribed fires (i.e., planned fires that are used to meet management objectives and that consider the safety of the public, weather, and probability of meeting burn objectives) and larger wildfires—as well as the benefit provided by different types of simple respiratory personal protective equipment.

The research team, led by principal investigators and bioengineers Jessica Oakes and Chiara Bellini of Northeastern University, hopes the three-year project will inform which fire scenarios are the most dangerous with greatest risk to firefighters’ pulmonary and cardiovascular health. Perhaps most importantly, it could lead to recommendations for respiratory personal protective equipment that is easily implemented in the field and/or possible changes in tactics to mitigate exposure, with the goal of preserving firefighters’ long-term health.

“Unlike structural firefighters, who will put on an air-purifying respirator or a self-contained breathing apparatus when they enter a building, wildland firefighters typically cover their face with only a simple bandana,” says Gollner. “Bandanas are a common tactic because they don’t add an additional burden of weight to firefighters’ already strenuous activity. However, it is unknown if, or to what extent, this provides health benefits.”

The research team will combine their expertise to solve this challenging problem: Gollner will contribute novel expertise in firefighting practices and fire generation, while Oakes and Bellini will offer interdisciplinary bioengineering expertise that’s critical to understanding this complex health problem. They will also work with the International Association of Fire Fighters and National Fire Protection Association to facilitate input from stakeholder partners including firefighters from several departments across the country, fire organization representatives, health researchers, governmental agencies, and members of technical committees overseeing personal protective equipment standards.

To learn more about Gollner’s research: