The fire burned over 96,000 acres and destroyed 1,600 structures in southern California in November, 2018

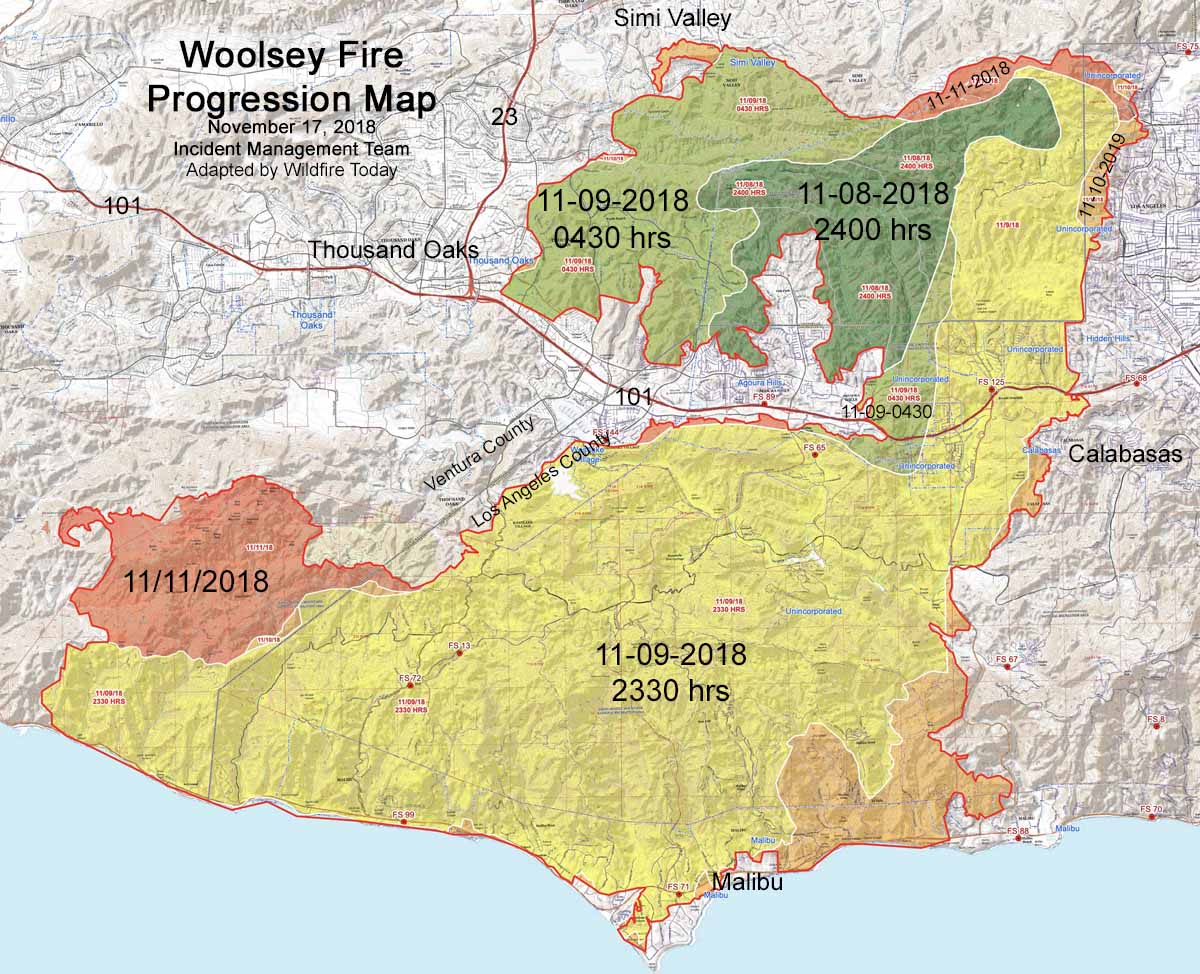

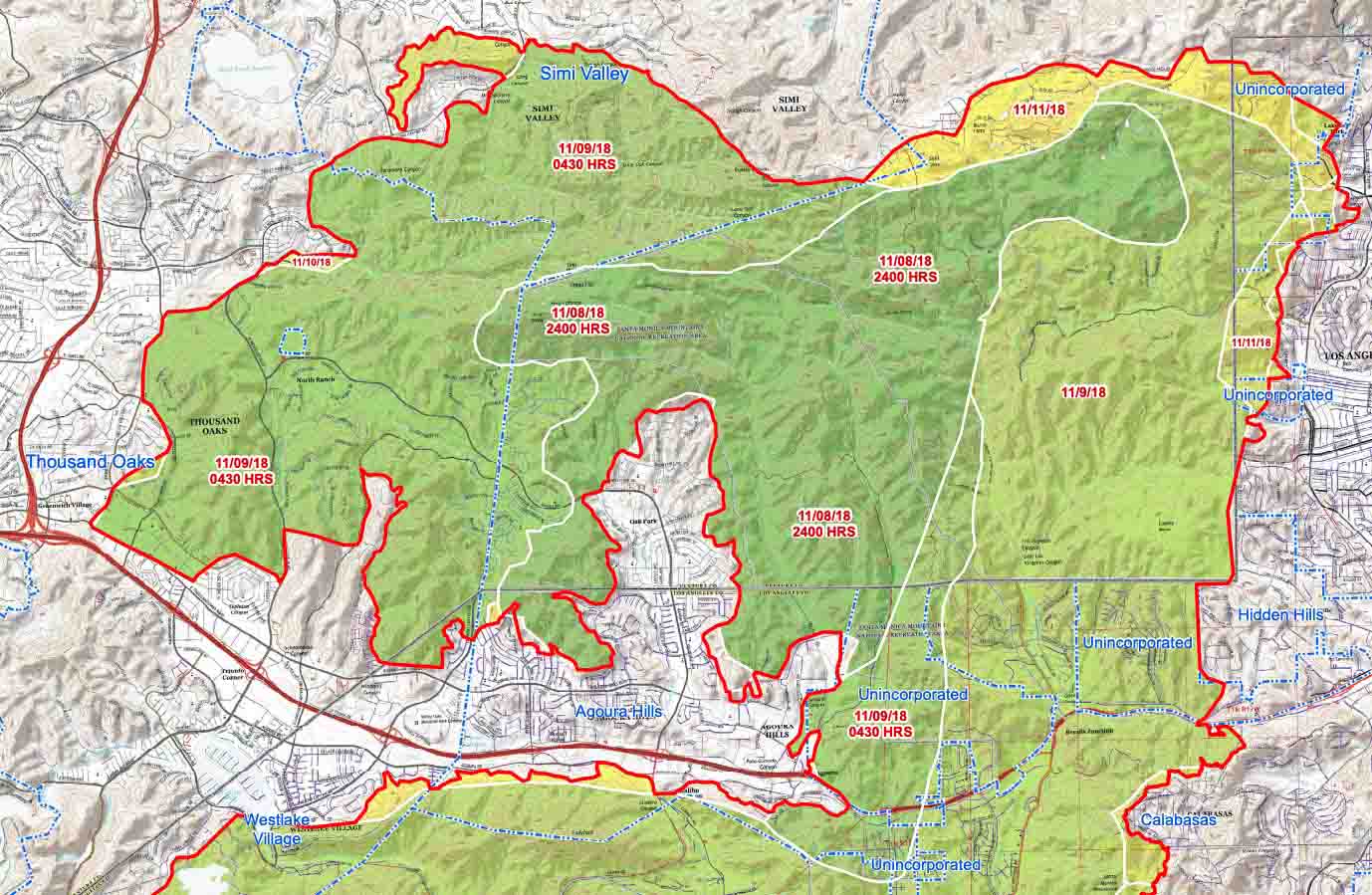

Above: Progression map of the Woolsey Fire, November 17, 2018. Perimeters produced by the Incident Management Team. Adapted by Wildfire Today.

A draft After Action Review was released by Los Angeles County that details some of the issues that affected the management and suppression of the Woolsey Fire that destroyed 1,600 structures and burned nearly 97,000 acres.

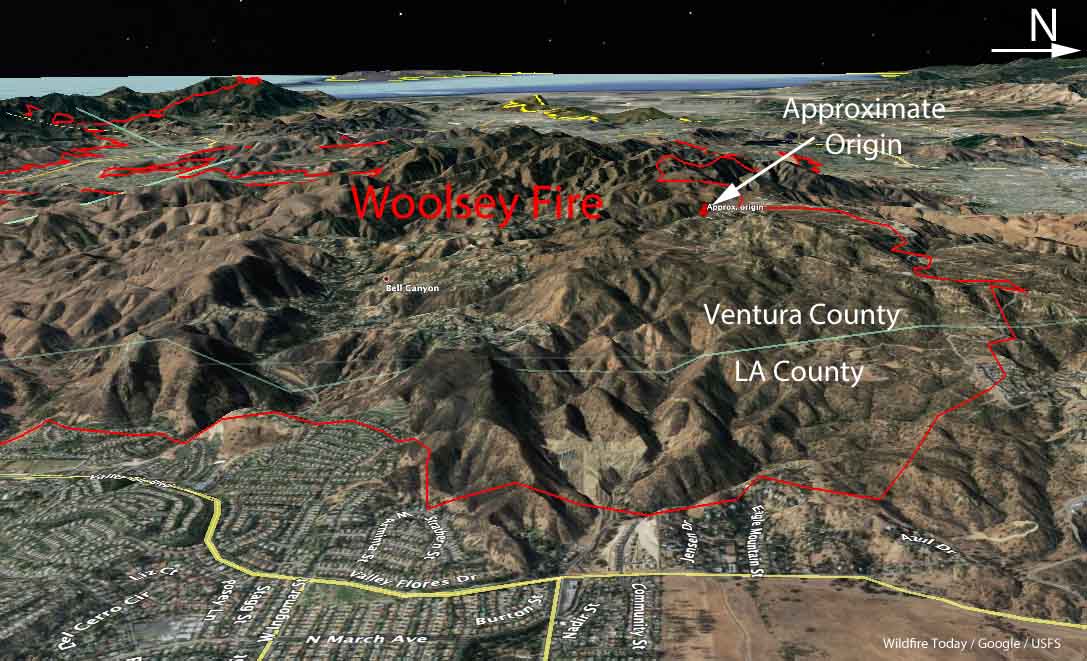

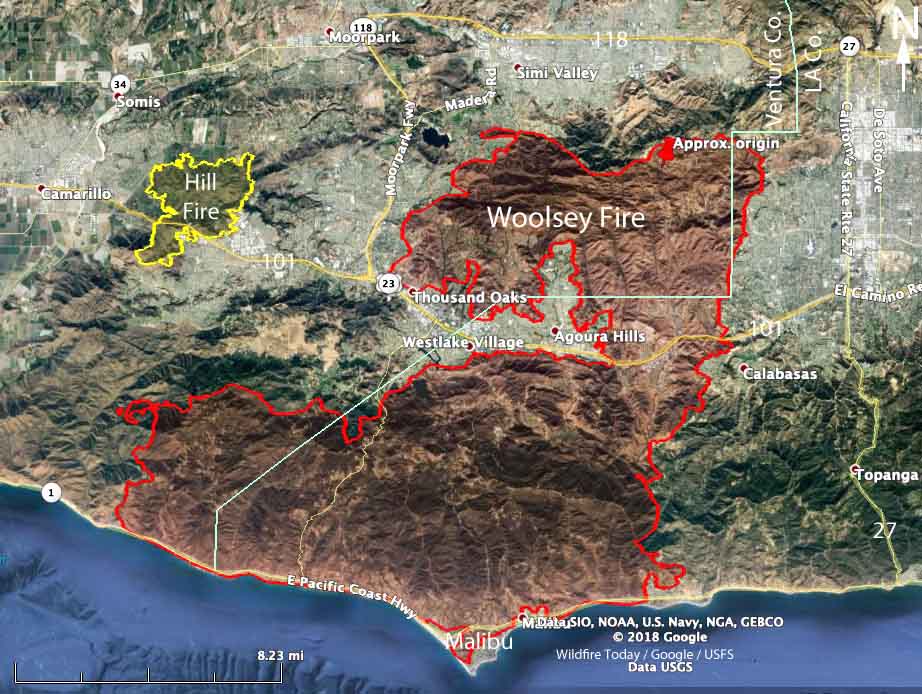

When fire started at about 2 p.m. on November 8, 2018 the humidity was five percent and the wind was gusting out of the north and northeast at 40 to 50 mph. At 5:15 the next morning, Friday November 9, it jumped the 12-lane 101 freeway and before noon it ran for another six miles to the Pacific Ocean, a distance of about 15 miles from the point where it started 22 hours before.

Thursday November 8 was a busy day in California. Just before midnight the night before there was a mass shooting incident leaving 12 dead at a bar in Thousand Oaks, just west of where the fire was hours later. The Camp Fire started early Thursday morning wiping out much of Paradise in northern California before noon. Then the Hill Fire started at about 1 p.m. south of Thousand Oaks about 13 miles southwest of where the Woolsey Fire started an hour later. The Hill Fire eventually burned over 4,500 acres and required the evacuation of 17,000 residents. While firefighters were still initially responding to the Hill Fire the Woolsey Fire ignited at about 2 p.m. Strike teams of engines and crews were already en route to northern California, so right away there was competition for firefighting resources with three major fires burning simultaneously in the state.

The Woolsey Fire started in Ventura County but spread into Los Angeles County. Very large portions of the blaze were in both counties, testing the capabilities of LA City, LA County, and the Ventura County Fire Department. The report states that even though the three organizations “regularly plan for and practice their response to a large fire in the region, they could not have planned for a complete exhaustion of California’s limited firefighting resources brought on by a regional wildfire weather threat in conjunction with the Camp Fire, a mass casualty shooting in Ventura County, and the Ventura County Hill Fire, which began just before the Woolsey Fire started.”

With large numbers of firefighting resources committed to the three major fires, and with the dry, windy weather continuing, many agencies had to think hard about continuing to send more and more firefighters to the Hill and Woolsey Fires in case more incidents broke out. Approximately half the resource orders for the Woolsey Fire were UTF, Unable to Fill.

The fire presented a number of complexities, according to the report:

- The location and topography, which presented severe challenges for initial attack.

- The early November sunset, which grounded non-night-flying aircraft.

- Early and mid-evening wind shifts when the fire was still outside heavily populated areas.

- The fire’s crossing of the 12-lane Highway 101 before dawn on Friday.

- The defense of both sides of the populated areas along Highway 101 consumed fire attack resources just as the fire began the run to Malibu.

- Very limited initial resources in Malibu Friday morning due to fire ferocity and fire- or wind-caused road damage blocking Santa Monica Mountain and Malibu roads, including evacuation routes.

In Los Angeles County 1,075 homes and 46 commercial structures were destroyed. Approximately 57,000 structures were saved.

The After Action Review was written by a consulting firm, Citygate Associates of Folsom, California. The draft 204-page document has 155 findings and 94 recommendations, including:

- Improve methods and tools for communicating with the public.

- There was not a clear, single, comprehensive voice speaking to evacuation, and not all notification tools were used or used often enough.

- There was an over-reliance on Twitter; care must also be taken to account for the digital divide in which not everyone is on Twitter or even the internet.

- Entry and repopulation policies were not well briefed to checkpoints or the public.

- There is a need for greater inter-agency pre-incident evacuation and repopulation planning for the communities in Fire Hazard Severity Zones. No pre-prepared traffic evacuation plans/scenarios exist for the areas impacted by the Woolsey Fire. Evacuation plans also need corresponding repopulation plans at the earliest moment.

- The following are needed to improve situational awareness: Research and investment in emerging technologies to reduce the “fog of war”. Increased practice, procedures, and technologies in melding the large County agency DOCs and Incident Management Teams (IMTs) into a virtual unified command, as if they were in one physical location, to reduce lag time in fast-tempo, complicated decisions. Real-time display of fire perimeter, hazards, actions, shelters, and evacuation orders for public consumption.

- Improve coordination of multiple-agency emergency public messages.

- Increase the speed and use of all alerting tools in wide-area, fast-paced disasters.

- Address the impact of long-distance fire storm ember spotting through education and an emphasis on using layered buffer zones of appropriate defensible space and structure hardening techniques.

- Encourage the major fire departments in the area to evaluate creating a sub-regional (three county) Multiple-Agency Coordination and Control Center within the State mutual aid system that will utilize technology to enhance situational awareness and create a shared, real-time intelligence, information, and command center on a round-the-clock basis. This concept should further existing agreements and enhance the ability of agencies to work collaboratively during the first one to two days of a catastrophic disaster, for the common welfare, at a pace faster than the Statewide mutual aid system can provide.

The county expects to hold at least two public meetings to present the report and solicit public input.

The Draft Woolsey Fire AAR is a very large 22 Mb file.

Click here to see all articles on Wildfire Today tagged “Woolsey Fire.”

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Tom. Typos or errors, report them HERE.