The House version of the 2018 Farm Bill would expand logging on public lands

One of the favorite responses of some politicians to devastating wildfires is to call for increased logging on public lands. Their reasoning is that having fewer trees will prevent large fires. The fact is that logging does not eliminate forest fires. For example, in a clear cut there is still fuel remaining, especially if the slash is left untreated, which can spread a fire faster than a forested area and can act as spot fire traps with dry, easily ignitable vegetation that is even more susceptible to propagating a fire from airborne burning embers up to a mile away from the main fire.

The House version of the 2018 Farm Bill being considered now would expand logging on public lands in response to recent increases in wildfires. A group of 217 scientists, educators, and land managers have signed an open letter calling on decision makers to facilitate a civil dialogue and careful consideration of the science to ensure that any policy changes will result in communities being protected while safeguarding essential ecosystem processes.

Below is an excerpt from the scientists’ letter:

What Is Active Management and Does It Work to Reduce Fire Activity?

Active management has many forms and needs to be clearly defined in order to understand whether it is effective at influencing fire behavior. Management can either increase or decrease flammable vegetation, is effective or ineffective in dampening fire effects depending on many factors, especially fire weather, and has significant limitations and substantial ecological tradeoffs.

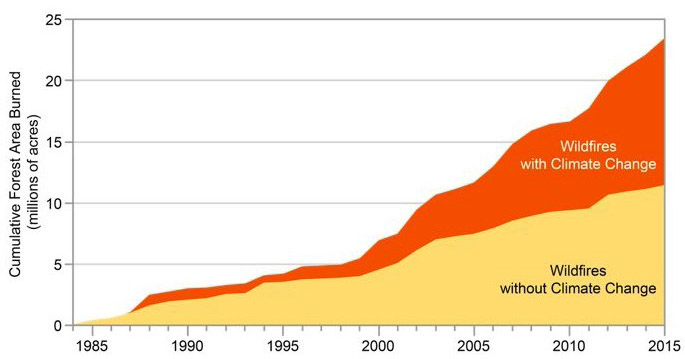

Thinning Is Ineffective in Extreme Fire Weather – Thinning is most often proposed to reduce fire risk and lower fire intensity. When fire weather is not extreme, thinning-from-below of small diameter trees followed by prescribed fire, and in some cases prescribed fire alone, can reduce fire severity in certain forest types for a limited period of time. However, as the climate changes, most of our fires will occur during extreme fire-weather (high winds and temperatures, low humidity, low vegetation moisture). These fires, like the ones burning in the West this summer, will affect large landscapes, regardless of thinning, and, in some cases, burn hundreds or thousands of acres in just a few days. Thinning large trees, including overstory trees in a stand, can increase the rate of fire spread by opening up the forest to increased wind velocity, damage soils, introduce invasive species that increase flammable understory vegetation, and impact wildlife habitat. Thinning also requires an extensive and expensive roads network that degrades water quality by altering hydrological functions, including chronic sediment loads.

Post-disturbance Salvage Logging Reduces Forest Resilience and Can Raise Fire Hazards – Commonly practiced after natural disturbances (such as fire or beetle activity), post-disturbance clearcut logging hinders forest resilience by compacting soils, killing natural regeneration of conifer seedlings and shrubs associated with forest renewal, increases fine fuels from slash left on the ground that aids the spread of fire, removes the most fire-resistant large live and dead trees, and degrades fish and wildlife habitat. Roads, even “temporary ones,” trigger widespread water quality problems from sediment loading. Forests that have received this type of active management typically burn more severely in forest fires.

Wilderness and Other Protected Areas Are Not Especially Fire Prone – Proposals to remove environmental protections to increase logging for wildfire concerns are misinformed. For instance, scientists recently examined the severity of 1,500 forest fires affecting over 23 million acres during the past four decades in 11 western states. They found fires burned more severely in previously logged areas, while fires burned in natural fire mosaic patterns of low, moderate and high severity, in wilderness, parks, and roadless areas, thereby, maintaining resilient forests.

Consequently, there is no legitimate reason for weakening environmental safeguards to curtail fires nor will such measures protect communities.

Closing Remarks and Need for Science-based Solutions

The recent increase in wildfire acres burning is due to a complex interplay involving human-caused climate change coupled with expansion of homes and roads into fire-adapted ecosystems and decades of industrial-scale logging practices. Policies should be examined that discourage continued residential growth in ecosystems that evolved with fire. The most effective way to protect existing homes is to ensure that they are as insusceptible to burning as possible (e.g., fire resistant building materials, spark arresting vents and rain-gutter guards) and to create defensible space within a 100-foot radius of a structure. Wildland fire policy should fund defensible space, home retrofitting measures and ensure ample personnel are available to discourage and prevent human-caused wildfire ignitions. Ultimately, in order to stabilize and ideally slow global temperature rise, which will increasingly affect how wildfires burn in the future, we also need a comprehensive response to climate change that is based on clean renewable energy and storing more carbon in ecosystems.

Public lands were established for the public good and include most of the nation’s remaining examples of intact ecosystems that provide clean water for millions of Americans, essential wildlife habitat, recreation and economic benefits to rural communities, as well as sequestering vast quantities of carbon. When a fire burns down a home it is tragic; when fire burns in a forest it is natural and essential to the integrity of the ecosystem, while also providing the most cost effective means of reducing fuels over large areas. Though it may seem to laypersons that a post-fire landscape is a catastrophe, numerous studies tell us that even in the patches where fires burn most intensely, the resulting wildlife habitats are among the most biologically diverse in the West.

For these reasons, we urge you to reject misplaced logging proposals that will damage our environment, hinder climate mitigation goals, and will fail to protect communities from wildfire.