The above-normal winter precipitation in California and over parts of the American West has already raised the question — even before the floodwaters have receded — of how this winter precip might either dampen the fuel beds or spawn a monster crop of fine fuels come spring and summer of 2023.

There’s a lot of winter and spring to come, and the first-of-the-month fire outlooks are 10 days out, but many are sensing that fire season in wetter locales will begin later. This delay is more likely in California, which is coping with a walloping by deep and repeated atmospheric rivers, resulting in near-record snowpack and flooding that may be familiar historically but not during the most recent drought decades.

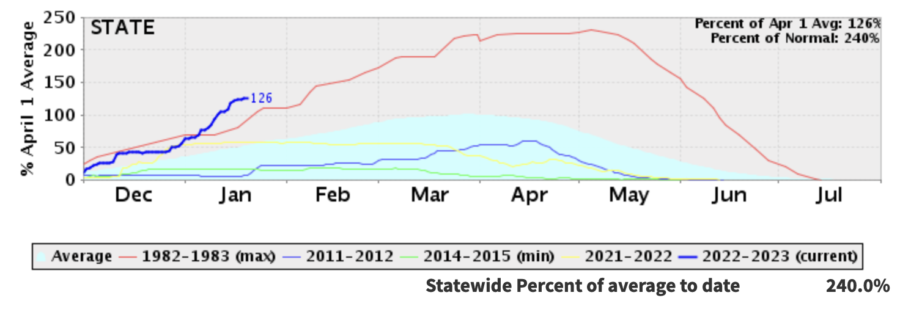

Consider the California snowpack as of Jan. 20, 2023. Whether by graph or map, the message is clear: the snowpack is significant and snowmelt periods will likely be extended. Statewide the snowpack is at 126% of the April 1 normal, but 240% for the current water year-to-date.

With a focus on California’s rapid switch from drought to flood, it’s clearly a banner water year to analyze — which is too painfully clear to the many who are working through a long recovery from flood damages estimated to exceed $1 billion. As CNN reported, at one point an estimated 90% of California’s population was under some form of flood watch, which equates to 10% of the US population.

Per California Water Watch, the state is at 167% of average precipitation for this date, but storms aren’t a universal event. While the map for accumulated water year precipitation beginning Oct. 1 shows higher departure from average over most of the state, the most-intense “purple” is being collected in the higher elevations in the central and northern mountains, and sopping the lower coastal regions that were hit full-force by the atmospheric rivers.

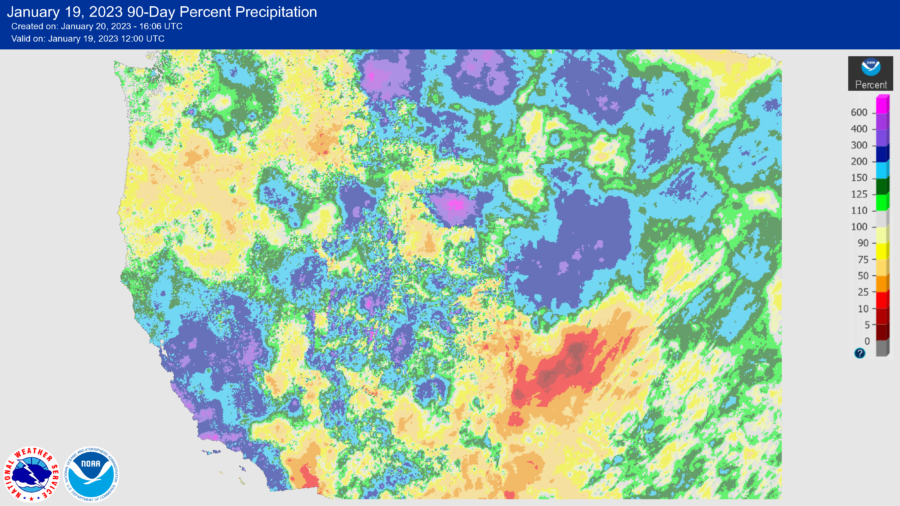

As damaging as the storms have been for so many communities, much of the West continues to feel the effects of long-term drought. A broader west-wide map of precipitation of the past three months shows the patchiness of these bomb cyclones.

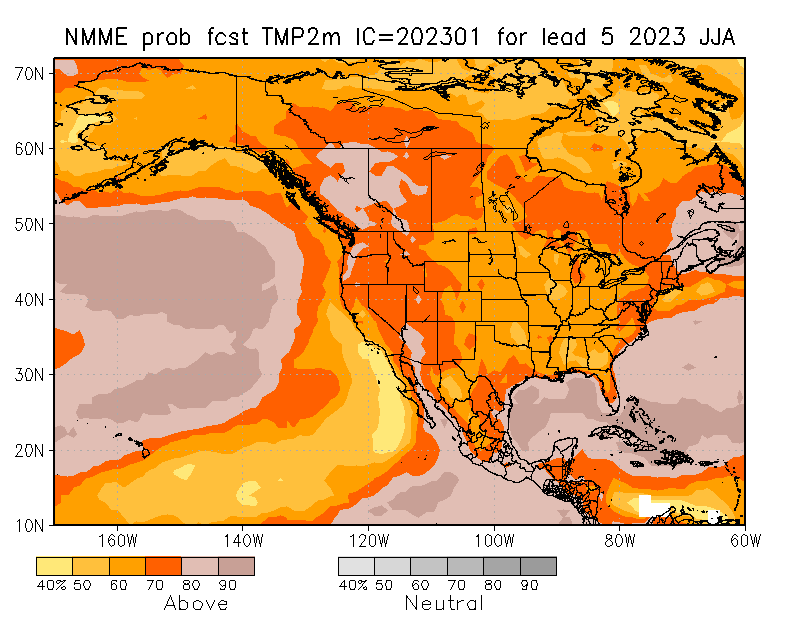

Looking ahead, a range of analysis tools foretell the potential of a warm summer and the likely impacts of long-term drought returning. The five-month lead for June-July-August (JJA), from the North American Multi-Modal Ensemble (or NMME), paints a warm picture for North America, with most of the U.S. West at 70% or higher likelihood for warmer than normal temps. Which will in turn elevate the evaporation potential during growing (and curing) season.

The same JJA outlook indicates a potential for most of North America to receive normal summer precip (though normal is often quite dry for much of the Western regions), with wetter likelihood for Alaska and drier than normal for western and northern Canada, the Pacific Northwest, the lower Mississippi Valley into Texas and south to Mexico and Central America.

How these ensemble outlooks play out will depend in part on a projected switch from La Niña to neutral or potentially El Niño conditions. And the impact of the winter’s snowpack will depend on how early and warm the spring temperatures rise. More on that potential when we look at the February outlooks.

Thanks to the Analysts … Many of these resources are digested from the outlooks and links prepared and shared by National and Geographic Area analysts. So a thanks for the work these folks do, season in and season out. This update owes much to the analysts who produced the January outlooks for Northern California and Southern California.