In the northwest portion of Lake Superior is a chunk of land of about 132,000 acres that is both a geographic novelty and an International Biosphere Reserve. The Isle Royale National Park is 56 miles off Michigan’s shore and 18 miles from Minnesota’s mainland. Congress designated the 50-mile-long island as a national park in 1931, but even before that it was apparent the island’s boreal forests had a close history with fire.

“Official fire record keeping began in 1847, when the first General Land Office survey of Isle Royale was conducted,” according to the park’s website. “These records show 31 fires between 1847 and 1898. Data suggests fire was more frequent and/or severe in the boreal forest of the island’s northeast end, compared with the northern hardwoods of the southwest end.”

The island’s dense concentration of high-flammability trees, e.g. balsam fir, black spruce, and jack pine, heightened the risk of wildfires igniting when lightning struck. A zoologist in 1931 recognized the important role fire played in the island’s unique ecosystem, but his ideas were discarded in favor of the system-wide preference toward fire suppression.

“In planning for improvements and facilities on Isle Royale, the National Park Service consulted with University of Michigan Zoologist Adolph Murie,” the park said. “Murie visited Isle Royale in June 1935 and recommended that no new trails be cleared by the CCC and all efforts be made to ‘guard against any sort of development which will reduce space or increase travel.’ He also recommended that forest fires be allowed to occur on Isle Royale, but this idea was rejected, and instead, an aggressive anti-forest-fire point of view was adopted.”

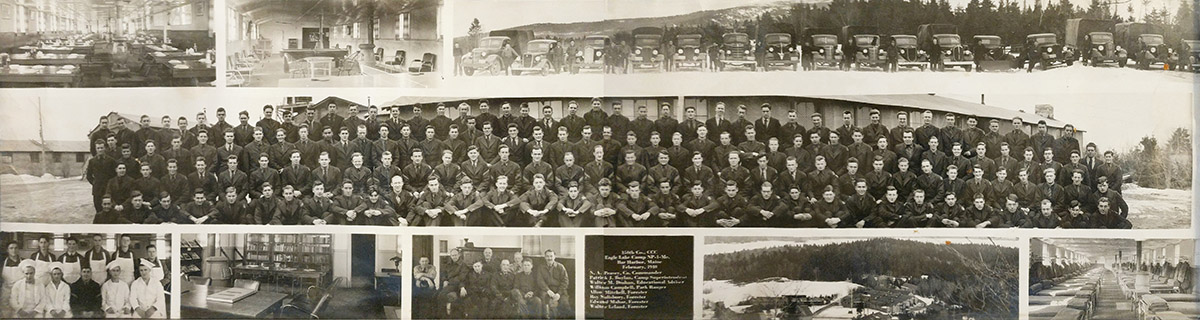

Officials would soon come to regret dismissing Murie’s ideas. Park historians describe the summer of 1936 as hot and dry. Hundreds of CCC enrollees arrived at the heavily logged and mined island to establish the park. On July 25, a fire started near the Consolidated Paper Company and, while a cause was never determined, the “Fire of 1936” would have the most profound effect on the natural and human history of Isle Royale compared with any other historical event.

Around 200 CCC members and loggers tried in vain to fight the fire as it grew from 200 to 5,000 acres over 10 days. The fire was reported as contained on August 4, but two spot fires that had ignited on August 2 would become much larger problems. By August 18, the three fires burned 27,000 acres before they were officially declared out after heavy rainfall.

Multiple factors contributed to the high number of acres burned in the fire, park historians said. The island’s ground was, at the time, mostly covered in highly flammable mosses. In-fighting between the park system and CCC members, including a short CCC strike when tobacco supplies ran out, likely made matters worse.

The island wouldn’t see significant wildfires again until the 2021 Horne Fire and the 2022 Mount Franklin Fire, which burned 335 acres and 6 acres respectively. In the fires’ wake, scientists and researchers hope to use the burned areas to learn more about the dynamics between fire and the island’s life.

The island wouldn’t see significant wildfires again until the 2021 Horne Fire and the 2022 Mount Franklin Fire, which burned 335 acres and 6 acres respectively. In the fires’ wake, scientists and researchers hope to use the burned areas to learn more about the dynamics between fire and the island’s life.

“The area may look different, but wildfire is an agent of necessary change,” the park said. “At the site of the Horne Fire, Isle Royale ecologists now have a living laboratory, and these researchers can begin to study the relationships between fire, living things, and an island environment.”

::: more about fire ecology research on the island :::