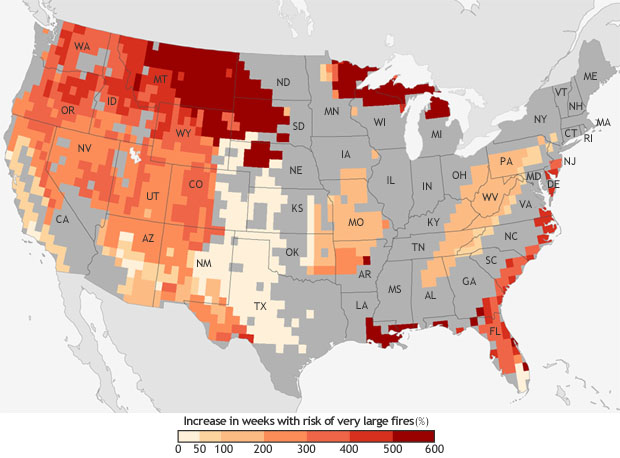

Researchers are predicting that beginning 26 years from now the number of weeks in which very large fires could occur will increase by 400 to 600 percent in portions of the northern great plains and the Northwest. Many other areas in the West will see a 50 to 400 percent increase.

If they are correct, the effects of climate change are not generations away. Firefighters starting out today will be dealing with this on a large scale during their careers.

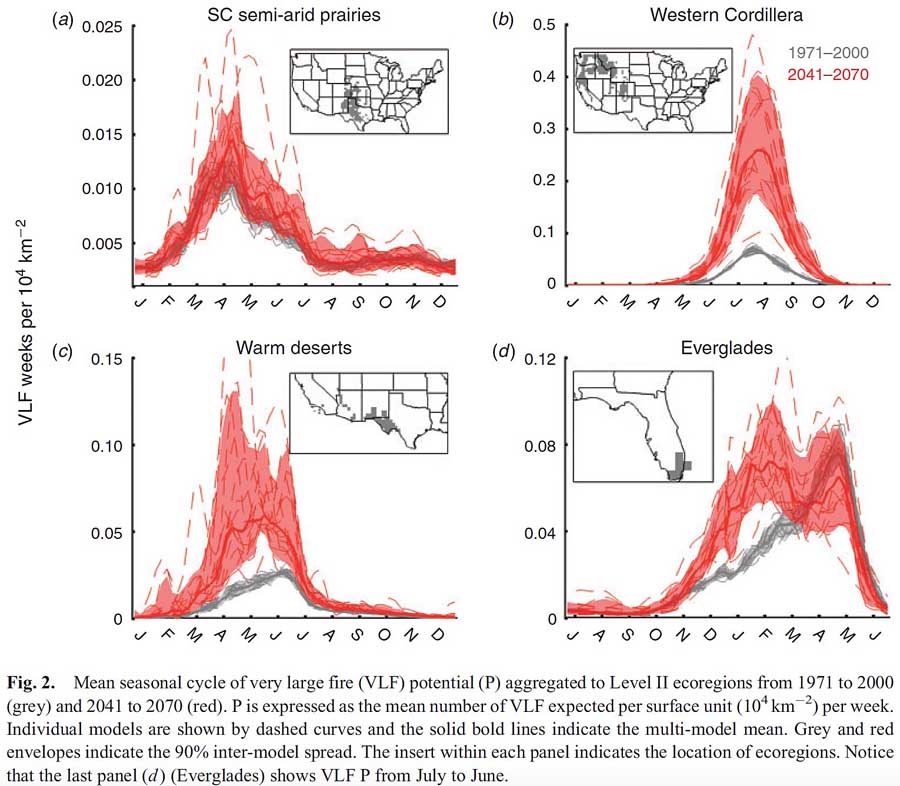

Warming due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions will likely increase the potential for ‘very large fires’—the top 10 percent of fires, which account for a majority of burned areas in many regions of the United States. Climate change is expected to both intensify fire-friendly weather conditions, as well as lengthen the season during which very large fires tend to spread.

The potential for very large fire events is also expected to increase along the southern coastline and in the forests around the Great Lakes, although the number of events along the northern tier of the country should only increase moderately given the historically low potential for these events.

For this study, researchers considered the average results of 17 climate model simulations to examine how the potential for very large fires is expected to change. Future projections* were based on a higher-emissions scenario called RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions.

Along with the elevated potential for very large fires across the western US in future decades, other climate modeling studies have projected increases in fire danger and temperature, and decreased precipitation and relative humidity during the fire season. The increased potential for these extreme events is also consistent with an observed increase in the number of very large fires in recent decades.

In addition, scientists have detected trends toward overall warming, more frequent heat waves, and diminished soil moisture during the dry season. The combination of these climate conditions and historic fire suppression practices that have led to the build-up of flammable debris have likely led to more frequent large fire events.

At this very moment, more than 56 large wildfires are burning uncontained throughout the West, putting homes, lives, and livelihoods at risk. The smoke created by these fires exacerbates chronic heart and lung diseases while also degrading visibility and altering snowmelt, precipitation patterns, water quality, and soil properties. In addition to public health impacts, projected trends in extreme fire events have important implications for terrestrial carbon emissions and ecosystems.

The authors of the study also note that these findings could place a burden on national and regional resources for fighting fires. Fire suppression costs in the U.S. have more than doubled in recent decades, exceeding $1 billion per year since the year 2000, the National Interagency Fire Center reports. The vast majority of that money is spent on large incidents.

The research was conducted by government employees at taxpayer expense, funded by NOAA, the U.S. Forest Service, and two universities. The authors were: Barbero, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Larkin, N.K.; Kolden, C.A.; and Stocks, B. The title: “Climate change presents increased potential for very large fires in the contiguous United States”. It was published in Australia in the International Journal of Wildland Fire (copies available for $25).

We checked with Frames.gov which posts copies of government-funded research, and were told by Michael Tjoelker, “Unfortunately, due to copyright issues we are not able to distribute full text versions of Journal articles.” However, Renaud Barbero, one of the authors, sent us a copy.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to (another) Bill.

Typos or errors, report them HERE.